“Just being there for someone for some time: that’s all it is. To know someone is there.”

— Kevin Briggs, retired CHP Officer

![]()

On March 11, 2005, Kevin Berthia woke up early and drove his ‘96 Buick Regal to the Golden Gate Bridge.

The 22-year-old Oakland native had never really thought about the bridge. He’d never taken a picture of the bridge. He didn’t even know how to get there. But he was certain, on this overcast day in early Spring, that he’d jump to his death from its rusty-orange arches.

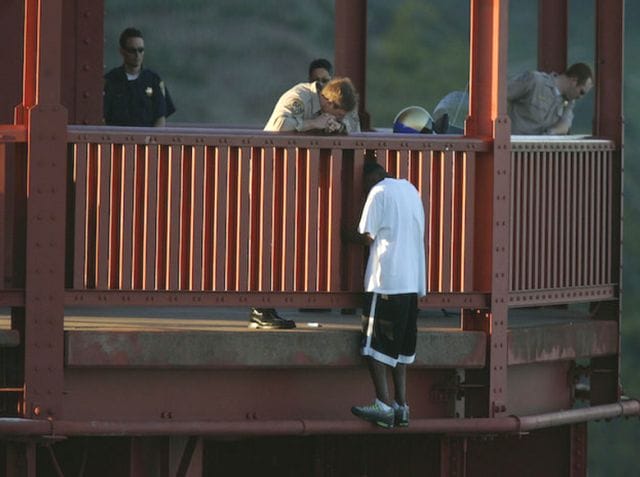

Kevin parked at the northern terminal and meandered up the walkway, slowly picking his way through mid-day joggers and camera-toting tourists. Just beyond the north tower, he turned off his cell phone; nobody had answered his final call. In a white t-shirt, basketball shorts, and Nikes, he could’ve just as easily been dressed for practice — but he was here, on the Golden Gate Bridge, to jump. He stopped, leaned against the metal bars, and scanned the distant waters. There was little time to ruminate: many things had brought him to this point, and it was too late to turn back.

With two steps, he lunged himself over the railing and onto a 6-inch-wide pipe, the only lifeline between him and the swirling bay 245 feet below. Trembling in the stiff wind, he closed his eyes, bent his knees and began to let go.

Then, he heard the voice.

***

The couple who adopted Kevin Berthia in 1983 — a secretary at the Port of Oakland, and a city arborist — did they best they could to provide a comfortable life in the rough and tumble city.

At five, he had to face the reality that he’d never know his biological parents — that they’d abandoned him at an agency a few days into life. At twelve, his adoptive parents filed for divorce; instantly, his life was split between two worlds. He remembers “feeling depressed [and] having bad thoughts,” but opted to bottle up his pain. Sports became his coping mechanism: “three practices a day, games on the weekends, repeat the cycle come Monday.” He stayed so involved that he didn’t have time to reflect.

As he entered high school two years later, “everything started to change:”

“I was so busy that I didn’t focus on issues; I had all this pain, but I was too tired to think about anything. I knew they existed. I knew that at night, they came crashing in and I felt a certain way — but I never really identified why I felt a certain way. I always had dark places I was in, or dark times that I was in, but I just tried my best to go to sleep and wake up knowing I had practice in the morning to distract me…

I always told the world I was fine. But secretly, in my own private time, I knew better.”

Soon, sports were no longer light-hearted and fun. Kevin was naturally gifted, but he felt tremendous pressure to succeed. Though he grappled with pain, he kept it to himself. As an African-American male in the macho, competitive world of athletics, talking about his feelings was “simply not an option.”

When Kevin graduated high school in 2002, he hadn’t attracted the interest of top college coaches; instead, he elected to attend the City College of San Francisco, just a 30-minute drive from Oakland. With a sparser schedule and only one sport to distract him instead of the six he’d once participated in, he began to falter emotionally. “For the first time in my life, I had this free time,” he tells us. “And in that free time, things started developing. It was time for me to think about the pain I’d felt as a kid.”

Kevin with his father (1985)

Just a few months into community college, he met a girl in class, fell in love, and dropped out to work a full-time job — to be, in her words, “a real man.” For the emotionally-reserved athlete, the relationship proved to be taxing: “I never really took care of the issues I had,” he says, “so, this new burden of taking care of someone else was a lot. Her problems became my problems.”

For two years, Kevin worked tirelessly; long, physically demanding days in construction drained him. His grand illusions of athletic stardom crumbled, and he gradually began to consider himself a failure:

“I put an enormous amount of pressure on myself — I felt like I wasn’t doing anything with my life. I had these high expectations, but I wasn’t playing sports, and I didn’t have any outlet. My job became my coping mechanism: I was over-worked, fatigued, so tired. I just saw myself changing.”

In 2002, after a “very intense” argument with his girlfriend, Kevin had a mental breakdown and pulled a knife on himself. He was hospitalized, went through extensive outpatient program at Kaiser, and, for the first time in his life, began to talk about his feelings — a process that, in his words, “only made things worse.” He was paraded from therapist to therapist, each time feeling more deflated than before:

“This was my first time ever talking to anybody, and they were telling me I shouldn’t be feeling the way I feel. “None of them attempted to understand how I felt — they were slamming a door in my face as far as trying to understand where I came from. It just made me feel worse.

I told myself ‘I’m never going to talk about these things ever again.’ Then I left, and put on a front for the world, like everything was okay.”

He returned to City College, put his head down, and began to excel – both as a student and an athlete. Exercising his remaining eligibility, he was named captain of the basketball team and was honored as player of the year in his conference. He let sports consume him, rid him of his tortured thoughts. Slowly, over the course of two years, he regained high hopes: when his season ended in February 2004, he was extended an offer to play overseas. Things were picking up. His life was steering back on course.

***

“We’re having a baby.”

The news, delivered from the lips of a new lover, came just days after he’d graduated, each word searing his chest like a hot iron. He’d always imaged his fatherhood in far-off vignettes: encouraging a first step, a first word, tossing a football in a park. And he’d told himself that he’d never leave his child — he’d always be there. But when his daughter was born in April 2004 — two-and-a-half months premature and weighing just one pound — he wasn’t ready.

A fleeting moment of joy was followed by an immense wave of terror, stress, and frustration. Negative mantras tortured him: I can’t do this; I’m not a father; I’ll never achieve my dreams. He declined the overseas offer and made an effort to invest himself in his child, but with years of bottled-up emotions, and now the immense obligation to care for another life, he entered a “downward spiral.”

He felt guilt — guilt for his daughter’s early birth, guilt for the constant arguments and uneasiness in his relationship, guilt for the way he felt, for his unpreparedness. A recent graduate, he had no job and no health insurance. The couple hadn’t expected a premature birth, and Kevin had banked on more time to find work and “get effects in order.” When the hospital bill came in the mail — $250,000 for 8 weeks of incubation — it devastated him.

He retreated.

Sixty miles away, he holed up with a friend and gradually shut off from the world. Ties with his mother disintegrated. Friends and family were shut out. His cell phone service was discontinued. When he eventually returned to Oakland, he was disoriented and disconnected — “beyond repair,” he says. He spent months trying to “mend” himself, but he was in a dark tunnel that kept getting longer with no sign of light.

On the morning of March 11, 2005, Kevin woke up with nothing left to give. Every issue in his life had converged, crushed him. I can’t fight anymore, he told himself.

Today, I leave the world.

This is it.

***

On the bridge, the wind comes in five-second gusts, each howling through steel beams like an injured timberwolf. It’s cold, damp, overcast. Tourists, eager to capture the fog-shrouded city, clog the walkways.

Spanning just under two miles from San Francisco to Marin County, the Golden Gate is a grand, towering structure. On the day it opened to public use in 1937, The Chronicle declared it a “thirty-five million dollar steel harp;” it’s since been deemed “the most beautiful, most photographed structure in the world,” and is a heralded as a marvel of engineering. But the bridge has a dark side not mentioned on its website: it is, by far, the most popular suicide destination in the United States — and the second most popular in the entire world, trailing only China’s Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge.

Estimates of the number of Golden Gate Bridge suicides widely vary — mainly because many victims’ bodies drift out to sea and are never recovered — but in 77 years, over 1,600 have been confirmed. Until 1995, an “official tally” was kept by the media, but as publicity mounted for the 1,000th jump (one local radio host even offered a case of Snapple to the “lucky” victim’s family), the count was disbanded.

Still, is it well-documented that between 20 and 40 people jump from the bridge every year.

A visualization of suicide locations on the bridge (1937-2005); Kevin was found just south of the Marin tower.

When a person leaps from the platform (220 to 245 feet high, depending on tides), he tumbles through the air for four seconds, before hitting the water at 75-80 miles-per-hour. Roughly 95% of jumpers die from impact trauma — crushed organs, shattered bones, snapped necks; most initial survivors find themselves paralyzed and quickly drown, or succumb to hypothermia in the frigid waters.

Incredibly, 34 people have survived the jump, most by way of a fortuitous gust of wind, or a perfect entry (feet-first, at a slight angle). In post-trauma psychological assessments, nearly every survivor relates that the split-second he let go, he immediately wished he hadn’t.

As Kevin Berthia hauled himself over the rail just beyond the Marin tower, he knew none of this. He hadn’t, like hundreds of jumpers before him, driven cross-country to get there, or researched various exit strategies in suicide forums. While his decision was the result of years of self-hatred, isolation, and hopelessness, his method was impulsive. But as he let his fingers slip off the beam, he had no regrets.

***

“What’s your plan for tomorrow?”

The voice was gruff — that of someone self-assured, someone who’d been there many times before. But the words, bellowed over deafening winds and rumbling semi-trucks, housed a kindness.

It stopped Kevin, snapped him “back into reality.” He hadn’t eaten for five days, hadn’t slept in a week, and struggled to find the energy to swivel around and clasp the rail. The bar was freezing — too cold to hold — so he let his head fall between the bars, and dangled there lifelessly with nothing but a stiff wind holding his 130-pound frame upright. For a moment, there was silence: The voice did not bark instructions, or make false claims — it waited for a response. It was there to listen.

And then, like an old toy slowly reanimating itself, Kevin began to talk.

“Everything that had always bothered me in life — from the adoption, to the divorce, to my failures as a father — everything that I never took the time to deal with was out there. The pain, the sorrow, the neglect. These things were now in front of me; I spoke them into existence.”

“For the first time in my life, I was really speaking,” he adds. “That man stole my heart hardly saying a word.”

He made himself vulnerable, gave himself up — all the while, not once looking up to see where the voice was coming from. It didn’t matter. Kevin stood on the precipice of death for 92 minutes; for all but three of them, he spoke. It was a one-way conversation — one that vastly differed from his traumatic experiences with therapists in the past: There was no ‘you shouldn’t feel like this,’ no ‘you need to get over it,’ no judgement. Just listening.

An hour and a half in, the conversation shifted. “You need to be here tomorrow,” said the voice, now closer. “You need to be here for your daughter.” All of Kevin’s negative energy — the pain, the suffering, the brooding thoughts — dissipated. “I had a newfound courage,” he recalls, “and felt empowered knowing what it was that bothered me.”

From here, Kevin’s memory goes hazy. He knows that he reached up with quivering arms and was hoisted up and over the rail. He remembers the flash of white lights, the roar of the helicopter overhead, the thickets of reporters and rubberneckers. He can still feel the hard plastic of the police car seat.

Somewhere en route to the unknown, he blacked out.

***

“You’re not leaving until you make progress — that’s the rule, you know.”

It was a new voice now, much less comforting, that jarred Kevin into consciousness. He was alone in a white room at Fremont Medical Center. All was still, quiet, calm. For seven days, he he’d remain here, recovering.

At first, he was “in denial of what had happened” and refused to talk or eat; wellness coaches came and went — each attempting to “reform” his depression without taking the time to understand where he came from:

“I didn’t even know what depression was. Where I grew up, we didn’t deal with depression, we didn’t know what depression or mental issues were. These things were never talked about, so it was hard for me to identify that this was my issue.”

After a week, he feigned his emotions, faked his way through therapy, and was released to the outside world.

It was here he saw the picture — a blaring, half-page shot on the front page of The San Francisco Chronicle — of himself, on the bridge. “It hurt me so bad to see myself in that white t-shirt up there,” he recalls. “I told myself: ‘I never want to see that picture. I never want to talk about it’… I just wanted to do everything I could to get over it.”

Throughout his experience on the bridge, Kevin had dislocated himself from reality; the image, in its starkness, made it factual. From then on, he did everything in his power to avoid talking about that day. Just like before, he retreated — and this time it was even worse: He’d endured something tragic and had to return to normal life, as if nothing had ever happened.

With his girlfriend and daughter in tow, he moved to Sacramento and tried to start a new life. He landed a job in construction and poured his “heart and soul” into the work: In three years’ time he’d ascended “from the bottom, as a will call guy,” to a warehouse supervisor running his own store; the work eventually found him relocated in San Jose — just an hour’s drive from the bridge.

Despite his professional success, it was a period of extreme lows and dark times. After pouring his heart out to that stranger that one day in March, he slunk back into emotional reclusiveness. He refused to talk, focused on distractions, and dipped in and out of depression medication.

“It was like the weight of world was on my shoulders,” he recalls. “I couldn’t breathe. I was so overwhelmed. I created this intense self-hatred — I hated myself.”

For eight years, he struggled to stay afloat.

***

After the incident, Kevin’s mother had sent a letter to the man who saved her son. “Nothing will erase the events of march 11,” she wrote, “but you are one of the reasons he is still with us; I truly believe he was crying out for help.”

Eight years later, when the man was invited to speak at an event for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, he invited her to share Kevin’s story. When she told her son the news, he refused to let her go alone: she’d just had a stroke, and it wouldn’t be safe to travel without company. Reluctantly, Kevin boarded the plane with his mother and set off for New York.

As the emcee spoke, Kevin waited anxiously backstage. In mere minutes, he’d walk across the platform and meet the man who saved his life — the man behind the voice.

***

Retired Sergeant Kevin Briggs has a set of eyes that seem to smile out of their own volition. At once youthful and weary, they’ve witnessed the full gamut of human emotion — from utter despondency to pure elation. He has the stoic, time-worn demeanor of a man who’s dealt with immense pain. His looks do not deceive.

Fresh out of high school, at 18 years old, Briggs joined the US Army — “the manly thing to do.” After three years of service, he was diagnosed with testicular cancer; he returned, endured chemotherapy, and beat the disease.

Determined to prove his worth, he became a guard for the California Department of Corrections, where he was assigned to San Quentin and Soledad, two of the state’s most notorious prisons. While there, a friend of his applied to the California Highway Patrol (CHP), and beckoned him to give it a shot too. Despite thinking that he lacked the intellect — “those guys are smarter than me!” he thought — he went through training and was signed soon signed on. For four years, he patrolled Hayward, an hour East of San Francisco; in 1994, he was transferred to Marin, which put the Golden Gate Bridge in his district.

He vaguely remembers his first suicide call: Middle aged woman, early 30s, perched precariously over the rail, crying. Years before, he’d gone through officer safety training, but nothing had remotely prepared him for this. “I was terrified,” he admits. “I didn’t know what the hell to do.” In the 1990s, suicides weren’t talked about in the police force — they weren’t something officers focused on. Briggs had to improvise, and he was successful; his patience, flexibility, and attentiveness coaxed her back over.

Sergeant Kevin Briggs, “Guardian of the Golden Gate Bridge” (Pivotal Points)

From then on, he was regularly called to the bridge to talk people down. He voraciously researched the psychology of suicidal people, trained in active listening skills, and eventually even had the opportunity to go through the FBI’s Crisis Intervention Training Program — something “very, very few patrolmen get to do.” Over a 23-year career, he became known as the “Guardian of the Golden Gate Bridge,” saving some 200 lives –sometimes, as many as two per month. Only two jumped after he interceded.

Often, conversations lasted late into the night — one went 7 hours before the man climbed back to safety. They always hinged around one skill: listening.

“I’m an introvert,” he cedes, “so its always been easier to listen than to talk.”

The day he received the call about Kevin in 2005 was no exception. “[Kevin] was very skittish,” he recalls. “My job was to build up trust with him very quickly. In that moment, I wasn’t an authority figure, I wasn’t a highway patrol officer to a civilian. It was just one joe to another.”

“Sometimes,” he adds, “it’s just easier to talk to damn near a stranger.”

As it turned out, the two strangers had much in common.

Like Kevin Berthia, Kevin Briggs never met his grandfather. “He committed suicide,” he says. “That act robbed me from ever getting to know him…I wonder, what he was like?”

Like Kevin Berthia, Kevin Briggs didn’t feel he could openly discuss his emotions, so he bottled them up. “Army, corrections, CHP — these were all heavy-end macho jobs,” he says. “Basically you’re not allowed to bring up personal feelings, or talk about yourself if you’re going through a hard time. It’s seen as a weakness.” It’s a mentality that taxes officers heavily: In the police force, suicide death rates double line of duty deaths.

And like Kevin Berthia, Kevin Briggs is no stranger to emotional turmoil. “I understand pain,” says Briggs, with a slightly defensive inflection. “I’ve been through cancer, I have three stints in my heart from heart attacks, went through a heavy duty divorce, had a pretty significant motorcycle crash that resulted in traumatic brain injury — all these things can lead to a mental illness, and they did.”

Kevin Berthia speaking in New York; via AFSP

Kevin Berthia emerges from behind the curtain to thunderous applause, and walks toward Briggs. He’s emotional and, for the first time in eight years, has no qualms about it: the tears come.

He’s face-to-face with the man now, shaking his hand, exchanging smiles. Briggs’ voice — the voice that brought Kevin, and many others back — is calming and assured. When Kevin hears it, it heals him, brings him acceptance and closure.

Behind Kevin, on a huge jumbo screen, the photo from the bridge looms. He turns around, faces it — the white t-shirt, the basketball shorts, the Nikes — and before the crowd of 200 survivors, researchers, and heroes, he accepts it. It is no longer a symbol of his weakness, but an emblem of his strength: I dealt with this. I beat this. I’m still here.

***

“I never thought that the worst day of my life could move people and change people like that,” Kevin tells us, over the phone. “I just started living mentally well last year — it’s like I’m free.”

Today, he is a proud homeowner in Manteca, a small city in Central Valley, California, 76 miles east of San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge. He’s fathered two more children since the day on the bridge, both sons — neither of whom would be here today if he’d jumped that day. He’s steeped in parenthood, eager to raise watch them grow.

He’s also since found gratifying work as a suicide prevention advocate. “I spend all my time learning about mental illnesses, sharing stories, helping people,” he says, with genuine pride. “For the first time in my life, I found something bigger than sports. This is my purpose.”

Sergeant Briggs, who Kevin is “good friends” with today, has also found new purpose: since retiring last year, he’s launched Pivotal Points, an organization that strives to “promote mental illness awareness, and show folks how much we can get done just by acknowledging each other.” His storied career has made him a ubiquitous figure in the press this year — TED talks, lectures, magazine shoots — but he continues to stress that he’s no hero. “When people come back over, I didn’t do it — they did it,” he insists. “It’s much harder to come back over that rail and continue on knowing that you may not improve. All I do is try to give you that chance.”

Most importantly, the macho-man has learned, like Kevin, that breaking down emotional barriers requires a special strength.

“There was a time I thought the bigger you were as a person, the more respect you would get,” cedes Briggs. “Now I know it’s not the size of you that really gets the respect — it’s what comes out of your mouth, and how you think. It’s just being there for someone for some time, to know someone is there…”

He pauses. For a moment, the phone static is the only sign he’s still there. We’re both silent.

“It’s listening.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett; you can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list. Cover photo © John Storey, licensed via Corbis.