In 1910, 89% of African Americans lived in the South. But by 1970, this was true of only 53% of the African American population.

This change, which has come to be know as “The Great Migration”, represents the largest internal movement of any group in American history. In “The Warmth of Other Suns”, Isabel Wilkerson’s chronicle of this crucial event, she writes:

It was during the First World War that a silent pilgrimage tooks its first steps within the border of this country. The fever rose without warning or notice or much in the way of understanding by those outside its reach. It would not end until the 1970s and would set into motion changes in the North and South that no one, not even the people doing the leaving, could have imagined at the start of it or dreamed would take nearly a lifetime to play out…

Historians would come to call it the Great Migration. It would become perhaps the most underreported story of the twentieth century…

Like so many before them, the men and women who were part of the Great Migration felt compelled to migrate to escape persecution and to search out economic opportunity. In the 20th Century, this meant the atrocities of the Jim Crow South combined with the employment opportunities afforded by labor shortages in the Industrial North. The combination led millions to leave the only world they knew for a new and uncertain life.

In many ways, the Great Migration consisted of many smaller migrations between local communities. The African Americans who left South Carolina were particularly likely to migrate to New York and Philadelphia, while migrants from Louisiana mostly headed to the great cities of the West.

We can track these patterns using data from the decennial census. This data sheds light on a momentous shift in American history.

The Great Migration: The African American Exodus from The South  In 1910, 89% of African Americans lived in the South. But by 1970, this was true of only 53% of the African American population. This change, which has come to be know as “The Great Migration”, represents the largest internal movement of any group in American history. In “The Warmth of Other Suns”, Isabel Wilkerson’s chronicle of this crucial event, she writes: It was during the First World War that a silent pilgrimage tooks its first steps within the border of this country. The fever rose without warning or notice or much in the way of understanding by those outside its reach. It would not end until the 1970s and would set into motion changes in the North and South that no one, not even the people doing the leaving, could have imagined at the start of it or dreamed would take nearly a lifetime to play out… Historians would come to call it the Great Migration. It would become perhaps the most underreported story of the twentieth century… Like so many before them, the men and women who were part of the Great Migration felt compelled to migrate to escape persecution and to search out economic opportunity. In the 20th Century, this meant the atrocities of the Jim Crow South combined with the employment opportunities afforded by labor shortages in the Industrial North. The combination led millions to leave the only world they knew for a new and uncertain life. In many ways, the Great Migration consisted of many smaller migrations between local communities. The African Americans who left South Carolina were particularly likely to migrate to New York and Philadelphia, while migrants from Louisiana mostly headed to the great cities of the West. We can track these patterns using data from the decennial census. This data sheds light on this momentous shift in American history.  The artist Jacob Lawrence depicted the Great Migration in a series of paintings in 1941. Following the Civil War, many African Americans hoped that the South could become a liveable place. As part of Reconstruction, the federal government took over the governance of the South and attempted to enforce civil rights for the newly freed people. The 13th, 14th and 15th constitutional amendments, passed between 1868 and 1870, were intended to assure that African Americans maintained their freedom, ability to vote, and equal protection under the law. These gains were short lived. By the late 1870s, the federal government withdrew from the South. Legislatures filled with white supremacists passed new laws that enforced segregation. These laws became known as “Jim Crow”. Wilkerson writes: Each year, people who had been able to vote or ride the train where they chose found that something they could do freely yesterday, they were prohibited from doing today. They were losing ground and sinking low in status with each passing day, and, well into the new century, the color codes would only grow to encompass more activities of daily life as quickly as they could devise them. Beyond discrimination and segregation, there was physical violence. From 1890 to 1910, at the very least, an average of 119 African Americans were lynched yearly, — sometimes simply because a white person accused them of acting “insolent”. Jamelle Bouie writes in the Nation about riots against the few prosperous African American communities that developed: …not only could you be killed for transgressing the nebulous and arbitrary social requirements of the Jim Crow, but you could also be killed for starting a business, accumulating wealth and otherwise trying to improve your situation. Economic opportunities were sparse. The war had destroyed the South’s economy and sources of wealth. There was little initial investment in the region. Not granted the land that many of them expected, many African Americans ended up working as sharecroppers for white landowners. These landowners often forced these sharecroppers into crippling debt by contracts signed under the the threat of violence. The First Wave of the Great Migration The First World War ignited the Great Migration. The war effort led to increased demand for industrial products made in the North, but also a labor shortage. With the native-born and immigrant populations usually relied upon off at war, companies looked south. “Northern companies offered well-paying jobs, free transportation, and low-cost housing as inducements to [African Americans] to move North,” writes the historian Spence Crew. “They also sent labor recruiters to the South who received a fee for every recruit they provided for the company they represented.” Hoping for a better life, many African Americans headed north. Historians usually divide The Great Migration into two periods: 1910-1940 and 1940-1970. These periods are separated by the lull in migration that happened during the Great Depression in the 1930s. The following chart displays the number of African Americans who migrated from the South to other parts of the country by decade.  Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Cato From 1910 to 1940, over 1.6 million African Americans left the South. They primarily headed to the cities of the Northeast, as well as Chicago and Detroit. Hundreds of thousands of migrants headed to the New York City area alone, bringing the number of African Americans in the New York City area from around 140,000 to over 650,000 in just thirty years. The population of New York City grew almost five times larger while the national African American population grew by about 30%. The table below displays the cities with the largest African American population in 1940, and how the population changed from 1910 to 1940. This table, and ones that follow, are estimates based on a one percent sample of the population.  Data: Census The conditions African Americans confronted in the North were improved but still full of hardship. Racism and prejudice abounded. Government policy kept African Americans out of many neighborhoods through redlining; the restriction of neighborhoods in which people of certain racial and ethnic groups could get approved for a mortgage. (Redlining remains an issue today.) These migrants worked in foundries, in meatpacking companies, as servants of the wealthy and on projects such as the expansion of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Spencer Crew writes, “[African Americans] typically wound up in dirty, backbreaking, unskilled and low-paying occupations. These were the least desirable jobs in most industries, but the ones employers felt best suited their black workers.” Still, these jobs often paid more than double than what the migrants would have received in the South. Only one quarter of the African Americans living in New York City by 1940 were born in New York State. In comparison, over one third of the African Americans living in New York City were born in South Carolina, Virginia or North Carolina. At almost 13% of the entire African American population in New York City, no migrant group was more common than those from South Carolina (less than 7% of all migrants during this period were from South Carolina). Many cities and states had unusually strong migratory relationships. Nearly half of the migrants who left Mississippi went to Chicago. African American Virginians migrated to Philadelphia at an uncommon rate. The table below shows the twenty cities with the largest African American population in 1940, and the most common birthplace of migrants to the state.  Data: Census Most of the patterns accord with geography. For cities on the East Coast, most migrants came from states on the East Coast. Midwestern cities like Chicago, St. Louis and Akron received an unusually large number of migrants from Mississippi and Alabama, states in the middle of the South. 22% of Chicago’s African American population in 1940 were migrants from Mississippi or Alabama. Los Angeles and San Francisco received migrants from the states furthest West. Of the more than 70,000 African Americans living in Los Angeles in 1940, 40% were born in either Texas, Louisiana or Oklahoma. But proximity does not explain all of the patterns. Georgia and South Carolina are similar distances from Cleveland, Ohio, but a migrant from Georgia was three times more likely to go to Cleveland than one from South Carolina. This can likely be explained by chain migration. Chain migration is the phenomenon of later migrants following earlier migrants. Just as this impacted European immigration to the United States — Irish following Irish to Boston, and Swedes following Swedes to Minneapolis — chaining helped determine the internal migration of African Americans in the United States. The Second Wave The movement of African Americans from the South slowed down during the depression era 1930s but came back stronger in the 1940s. Just as the First World War spurred the first phase of the Great Migration, Second World War jumpstarted the second. In the early 1940s, African Americans in the South continued to face the injustices of Jim Crow and an economy that afforded them little possibility to thrive. The number of agriculture jobs, a main source of work for the population, decreased due to mechanization and government policy discouraging land use. At the same time, the war effort caused an industrial boom in the western and northern cities of the country. There was a massive need for additional labor in shipyards and aircraft plants, and, like in the First World War, a great shortage of workers. Seeing this opportunity, African Americans left the South in huge numbers. In the 1940s alone, 1.4 million African Americans migrated—nearly as many as in the past three decades combined. In total, over three and a half million people migrated from 1940 to 1970. The historian James N. Gregory writes of the the incredible influence of the second phase of the Great Migration: Apart from the introduction of automobiles, it would be hard to think of anything that more dramatically reshaped America’s big cities in the twentieth century than the relocation of the nation’s black population. This began with the first era of migration, but the most dramatic changes occurred as a result of the second phase… …the growing concentration [of African Americans] in major cities had keyed dramatic reorganizations of metropolitan space, accelerating the development of suburbs and shifting tax resources, government functions, private-sector jobs, and a great many white people out of core cities. This next table shows the change in population for the twenty cities that had the largest African American populations in 1940, and the state from which that city had the most migrants. The African American population grew by about 70% during this period as a whole.  Data: Census The African American populations of the Northeast and Midwest continued to grow at a rapid pace, but it was the African American migration West that distinguishes the second phase. In just thirty years, the populations of Los Angeles (76,200 to 765,800) and San Francisco/Oakland (21,600 to 331,700) grew ten times larger. The Los Angeles area needed labour to fill over $11 billion dollars in war contracts to produce automobiles and steel. The African American population in San Francisco grew six times larger just from 1940 to 1945 due, in large part, to men coming to work on the naval shipyards.  African Americans who moved as part of the Great Migration continued to face discrimination. The migrants of the second wave of the Great Migration still encountered a world of persecution. Cuahutemoc Arroyo, who has researched post-War race relations in the San Francisco Bay Area, explains: Although the shipbuilding industry on the West coast provided relatively better economic opportunities than the Jim Crow South, blacks were still forced to adhere to a subservient role in society. They still had to confront the realities of being black. They were racially discriminated against within the workplace and in their communities. Within the shipyards blacks were confined to menial, unskilled positions. Blacks were forced to settle into segregated neighborhoods in the East Bay. Redlining and restrictive covenants kept blacks in the older and most deteriorated sections of the East Bay. Just as in the first phase of the Great Migration, the African Americans who moved out to the West Coast were mostly from Texas and Louisiana. Generally, the geographic patterns of the second wave were similar to the first. The table below shows the twenty cities with the largest African American population in 1970, and the most common birthplace of migrants to the state.  Data: Census *** The Great Migration ended in the 1970s. The impetus to move had lessened. The economies of the North and West had slowed, and through years of struggle African Americans in the South had gained greater equality. And at about that time, the economy of the South improved, with a pace of growth equal or greater than other regions of the country. In fact, almost immediately after the Great Migration ended, a reverse migration back to the South began. It’s still ongoing. Research by Brookings Institution demographer William Frey shows that, since 1970, more African Americans have moved to the South than any other region. African Americans leaving the Northeast are 50% more likely to move to the South than white Americans who migrate to other parts of the country. African Americans moving to the South during this period have been particularly attracted to large metropolitan areas, with Atlanta and Houston seeing particularly large gains. College educated African Americans are among the most likely to head South from the Northeast and Midwest. Frey writes that the reverse migration, “reflects the South’s economic growth and modernization, its improved race relations, and the longstanding cultural and kinship ties it holds for black families.” *** The impact of the Great Migration on American life is difficult to overstate. The economies, politics, and culture of America’s great cities were forever changed. Isabel Wilkerson writes in The Warmth of Other Suns: Its imprint is everywhere in urban life. The configuration of the cities as we know them, the social geography of the black and white neighborhoods, the spread of the housing project as well as the rise of a well-scrubbed black middle class, along with the alternating waves of white flight and suburbanization — all of these grew, directly or indirectly, from the response of everyone touched by the Great Migration. If millions African Americans had not migrated from the South to northern cities, the modern United States would look completely different. Contemporary American life is, in many ways, a ramification of this far-reaching, but underreported, historical event.”>

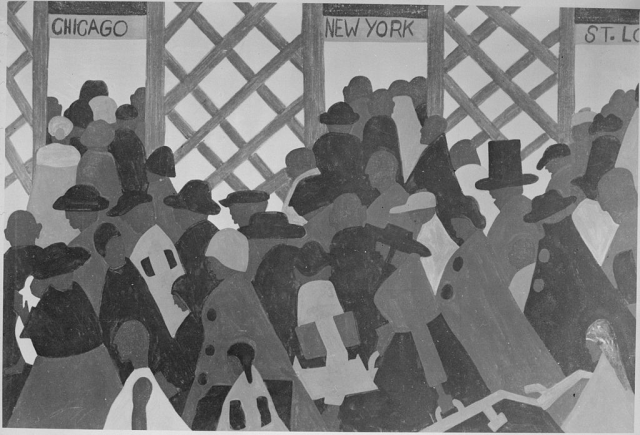

The artist Jacob Lawrence depicted the Great Migration in a series of paintings in 1941.

Following the Civil War, many African Americans hoped that the South could become a liveable place. As part of Reconstruction, the federal government took over the governance of the South and attempted to enforce civil rights for the newly freed people. The 13th, 14th and 15th constitutional amendments, passed between 1868 and 1870, were intended to assure that African Americans maintained their freedom, ability to vote, and equal protection under the law.

These gains were short lived. By the late 1870s, the federal government withdrew from the South. Legislatures filled with white supremacists passed new laws that enforced segregation. These laws became known as “Jim Crow”. Wilkerson writes:

Each year, people who had been able to vote or ride the train where they chose found that something they could do freely yesterday, they were prohibited from doing today. They were losing ground and sinking low in status with each passing day, and, well into the new century, the color codes would only grow to encompass more activities of daily life as quickly as they could devise them.

Beyond discrimination and segregation, there was physical violence. From 1890 to 1910, at the very least, an average of 119 African Americans were lynched yearly, — sometimes simply because a white person accused them of acting “insolent”. Jamelle Bouie writes in the Nation about riots against the few prosperous African American communities that developed:

…not only could you be killed for transgressing the nebulous and arbitrary social requirements of the Jim Crow, but you could also be killed for starting a business, accumulating wealth and otherwise trying to improve your situation.

Economic opportunities were sparse. The war had destroyed the South’s economy and sources of wealth. There was little initial investment in the region. Not granted the land that many of them expected, many African Americans ended up working as sharecroppers for white landowners. These landowners often forced these sharecroppers into crippling debt by contracts signed under the the threat of violence.

The First Wave of the Great Migration

The First World War ignited the Great Migration. The war effort led to increased demand for industrial products made in the North, but also a labor shortage. With the native-born and immigrant populations usually relied upon off at war, companies looked south.

“Northern companies offered well-paying jobs, free transportation, and low-cost housing as inducements to [African Americans] to move North,” writes the historian Spence Crew. “They also sent labor recruiters to the South who received a fee for every recruit they provided for the company they represented.”

Hoping for a better life, many African Americans headed north.

Historians usually divide The Great Migration into two periods: 1910-1940 and 1940-1970. These periods are separated by the lull in migration that happened during the Great Depression in the 1930s. The following chart displays the number of African Americans who migrated from the South to other parts of the country by decade.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Cato

From 1910 to 1940, over 1.6 million African Americans left the South. They primarily headed to the cities of the Northeast, as well as Chicago and Detroit.

Hundreds of thousands of migrants headed to the New York City area alone, bringing the number of African Americans in the New York City area from around 140,000 to over 650,000 in just thirty years. The population of New York City grew almost five times larger while the national African American population grew by about 30%.

The table below displays the cities with the largest African American population in 1940, and how the population changed from 1910 to 1940. This table, and ones that follow, are estimates based on a one percent sample of the population.

Data: Census

The conditions African Americans confronted in the North were improved but still full of hardship. Racism and prejudice abounded. Government policy kept African Americans out of many neighborhoods through redlining; the restriction of neighborhoods in which people of certain racial and ethnic groups could get approved for a mortgage. (Redlining remains an issue today.)

These migrants worked in foundries, in meatpacking companies, as servants of the wealthy and on projects such as the expansion of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Spencer Crew writes, “[African Americans] typically wound up in dirty, backbreaking, unskilled and low-paying occupations. These were the least desirable jobs in most industries, but the ones employers felt best suited their black workers.” Still, these jobs often paid more than double than what the migrants would have received in the South.

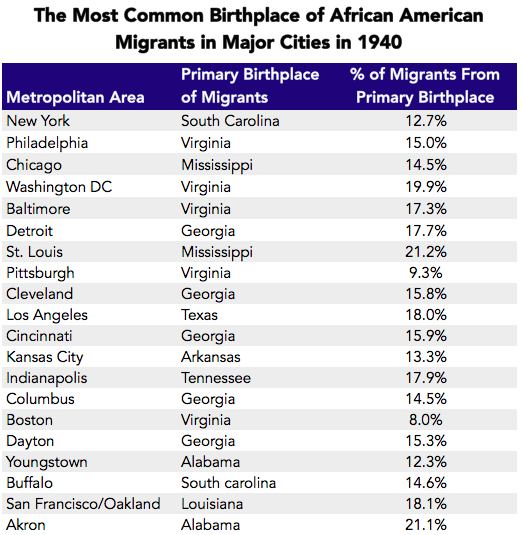

Only one quarter of the African Americans living in New York City by 1940 were born in New York State. In comparison, over one third of the African Americans living in New York City were born in South Carolina, Virginia or North Carolina. At almost 13% of the entire African American population in New York City, no migrant group was more common than those from South Carolina (less than 7% of all migrants during this period were from South Carolina).

Many cities and states had unusually strong migratory relationships. Nearly half of the migrants who left Mississippi went to Chicago. African American Virginians migrated to Philadelphia at an uncommon rate.

The table below shows the twenty cities with the largest African American population in 1940, and the most common birthplace of migrants to the state.

Data: Census

Most of the patterns accord with geography.

For cities on the East Coast, most migrants came from states on the East Coast. Midwestern cities like Chicago, St. Louis and Akron received an unusually large number of migrants from Mississippi and Alabama, states in the middle of the South. 22% of Chicago’s African American population in 1940 were migrants from Mississippi or Alabama.

Los Angeles and San Francisco received migrants from the states furthest West. Of the more than 70,000 African Americans living in Los Angeles in 1940, 40% were born in either Texas, Louisiana or Oklahoma.

But proximity does not explain all of the patterns. Georgia and South Carolina are similar distances from Cleveland, Ohio, but a migrant from Georgia was three times more likely to go to Cleveland than one from South Carolina.

This can likely be explained by chain migration. Chain migration is the phenomenon of later migrants following earlier migrants. Just as this impacted European immigration to the United States — Irish following Irish to Boston, and Swedes following Swedes to Minneapolis — chaining helped determine the internal migration of African Americans in the United States.

The Second Wave

The movement of African Americans from the South slowed down during the depression era 1930s but came back stronger in the 1940s. Just as the First World War spurred the first phase of the Great Migration, Second World War jumpstarted the second.

In the early 1940s, African Americans in the South continued to face the injustices of Jim Crow and an economy that afforded them little possibility to thrive. The number of agriculture jobs, a main source of work for the population, decreased due to mechanization and government policy discouraging land use.

At the same time, the war effort caused an industrial boom in the western and northern cities of the country. There was a massive need for additional labor in shipyards and aircraft plants, and, like in the First World War, a great shortage of workers.

Seeing this opportunity, African Americans left the South in huge numbers. In the 1940s alone, 1.4 million African Americans migrated—nearly as many as in the past three decades combined. In total, over three and a half million people migrated from 1940 to 1970. The historian James N. Gregory writes of the the incredible influence of the second phase of the Great Migration:

Apart from the introduction of automobiles, it would be hard to think of anything that more dramatically reshaped America’s big cities in the twentieth century than the relocation of the nation’s black population. This began with the first era of migration, but the most dramatic changes occurred as a result of the second phase…

…the growing concentration [of African Americans] in major cities had keyed dramatic reorganizations of metropolitan space, accelerating the development of suburbs and shifting tax resources, government functions, private-sector jobs, and a great many white people out of core cities.

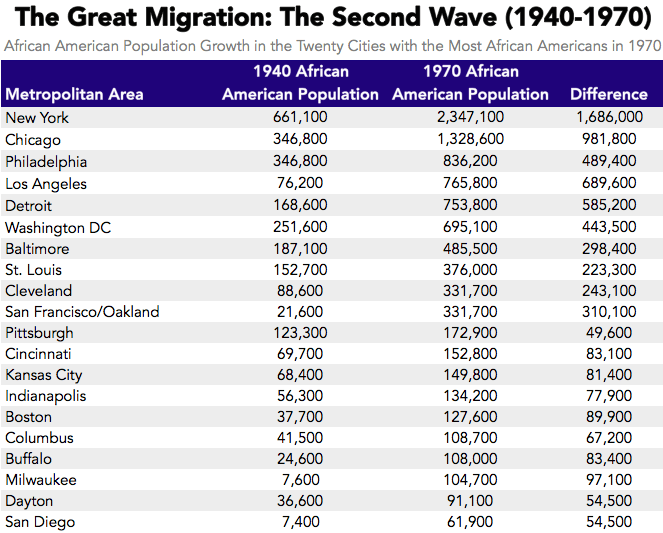

This next table shows the change in population for the twenty cities that had the largest African American populations in 1940, and the state from which that city had the most migrants. The African American population grew by about 70% during this period as a whole.

Data: Census

The African American populations of the Northeast and Midwest continued to grow at a rapid pace, but it was the African American migration West that distinguishes the second phase. In just thirty years, the populations of Los Angeles (76,200 to 765,800) and San Francisco/Oakland (21,600 to 331,700) grew ten times larger. The Los Angeles area needed labour to fill over $11 billion dollars in war contracts to produce automobiles and steel. The African American population in San Francisco grew six times larger just from 1940 to 1945 due, in large part, to men coming to work on the naval shipyards.

African Americans who moved as part of the Great Migration continued to face discrimination.

The migrants of the second wave of the Great Migration still encountered a world of persecution. Cuahutemoc Arroyo, who has researched post-War race relations in the San Francisco Bay Area, explains:

Although the shipbuilding industry on the West coast provided relatively better economic opportunities than the Jim Crow South, blacks were still forced to adhere to a subservient role in society. They still had to confront the realities of being black. They were racially discriminated against within the workplace and in their communities. Within the shipyards blacks were confined to menial, unskilled positions. Blacks were forced to settle into segregated neighborhoods in the East Bay. Redlining and restrictive covenants kept blacks in the older and most deteriorated sections of the East Bay.

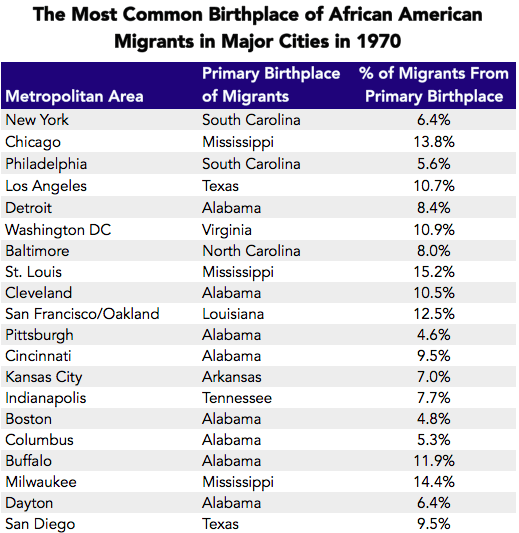

Just as in the first phase of the Great Migration, the African Americans who moved out to the West Coast were mostly from Texas and Louisiana. Generally, the geographic patterns of the second wave were similar to the first. The table below shows the twenty cities with the largest African American population in 1970, and the most common birthplace of migrants to the state.

Data: Census

The Reverse Migration

The Great Migration ended in the 1970s. The impetus to move had lessened. The economies of the North and West had slowed, and through years of struggle African Americans in the South had gained greater equality. And at about that time, the economy of the South improved, with a pace of growth equal or greater than other regions of the country.

In fact, almost immediately after the Great Migration ended, a reverse migration back to the South began. It’s still ongoing. Research by Brookings Institution demographer William Frey shows that, since 1970, more African Americans have moved to the South than any other region. African Americans leaving the Northeast are 50% more likely to move to the South than white Americans who migrate to other parts of the country.

African Americans moving to the South during this period have been particularly attracted to large metropolitan areas, with Atlanta and Houston seeing particularly large gains. College educated African Americans are among the most likely to head South from the Northeast and Midwest. Frey writesthat the reverse migration, “reflects the South’s economic growth and modernization, its improved race relations, and the longstanding cultural and kinship ties it holds for black families.”

***

The impact of the Great Migration on American life is difficult to overstate. The economies, politics, and culture of America’s great cities were forever changed. Isabel Wilkerson writes in The Warmth of Other Suns:

Its imprint is everywhere in urban life. The configuration of the cities as we know them, the social geography of the black and white neighborhoods, the spread of the housing project as well as the rise of a well-scrubbed black middle class, along with the alternating waves of white flight and suburbanization — all of these grew, directly or indirectly, from the response of everyone touched by the Great Migration.

If millions of African Americans had not migrated from the South to northern cities, the modern United States would look completely different. Contemporary American life is, in many ways, a ramification of this far-reaching, but underreported, historical event.

![]()

For our next post, we explore the data behind 48 selfie-induced deaths. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Dan Kopf; follow him on Twitter here.