Photo credit: John DS via Wikipedia

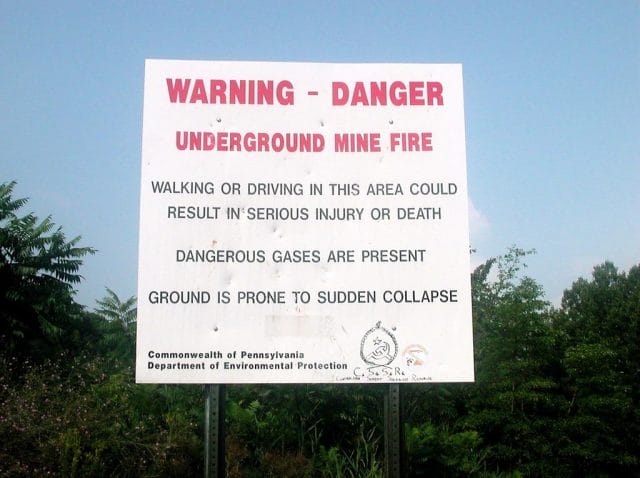

Not many people can claim Hell as their hometown. But Todd Domboski, and the several thousand former residents of Centralia, Pennsylvania, come closest to that distinction. In 1981, a 12 year-old Domboski fell into a pit that suddenly appeared in his grandmother’s backyard. He grabbed onto a tree root, and his cousin pulled him out from the steam-emitting hole in the earth. The cave-in was caused by one of the worst coal fires in American history — a fire that has been burning for over 50 years and may burn for several more centuries.

In 1960, Centralia, Pennsylvania, was a small town situated on top of a large supply of coal. Like many coal towns, the land’s natural riches had meager returns for residents. As journalist Joan Quigley relates in The Day The Earth Caved In, it was the type of town where at the sound of a siren, mothers would follow it to the coal mines, praying that their sons and husbands escaped the latest mine accident unharmed.

The fire began in a town dump. At first, no one was particularly concerned. Small fires started regularly; the town often organized controlled burns to help deal with the smell. At one point, the town’s volunteer firefighters recruited several teenagers to keep the water hose pointed at the smoldering garbage. When the teenagers grew tired, they used garbage to pin the hose in the right direction and left. The firefighters found the garbage pit covered in several inches of water the next morning.

Gradually town officials became more alarmed. The dump had once been the site of strip mining, and the town’s general funds were stretched thin every year keeping up with regulations to add nonflammable barriers between the garbage and the base of the pit. The exact cause of the fire is unclear; Quigley cites someone dumping smoldering coals at the dump (a routine practice) that escaped their container and caused a fire that reached the below coal mine through an unsealed opening. Others suggest a fire from another coal mine lit the veins beneath Centralia. But with each stepped up effort to master the flames that failed to keep steam from appearing within the next few days, it became clear a coal fire was at fault.

Town officials informed the mining company and the state about the fire while, as Quigley writes, vapor and fumes drifted from the garbage pit to nearby roads and buildings. Yet the tragedy unfolded at a glacial pace. Mining engineers understood the urgency of controlling the conflagration, but the first large-scale effort did not take place until one month later (3 months after the fire started) as various coal companies with mining rights, the state, and the federal government negotiated who would pick up the tab.

Meanwhile, life in the town continued. Changes in fuel preferences meant that Centralia’s mines, while still rich in coal, were already slowing down. The fire was more of a curiosity than a disaster; some residents enjoyed not needing to shovel as much snow as the ground heated. One woman recalled that she enjoyed harvesting tomatoes over the Christmas holiday.

The first effort to tame the fire — by digging down to extinguish the fire at its source — failed. It fed the fire with more oxygen, and the fire had spread farther than was estimated. A second effort to suffocate the fire with nonflammable fill also failed, as did further efforts to dig down and cut off the fire with trenches. By 1963, the state essentially gave up on extinguishing the fire and only made efforts to contain select blazes. Analysis typically blames the slow, underfunded initial responses for allowing the fire to get to a size that extinguishing it would cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Photo credit: Lyndi and Jason via Flickr

Despite being perched on a nearly eternal fire, life in Centralia continued for another two decades. Over time, the fire spread underneath the entire town, leading to cracked roadways and vents of steam. But as journalist Kevin Krajick relates, “To a certain degree, coal field residents who are in no immediate danger accept fires as part of the backdrop, like subway noise in New York City or drizzle in Seattle.” Residents joked about a cemetery situated near the original garbage pit that you could get buried and cremated at the same time. It wasn’t until events like young Todd Domboski’s nearly fatal plunge in the early 1980s that the fire attracted substantial media attention. Some residents installed carbon-monoxide monitors, community groups debated the problem, and anxious families asked how the fire would affect their health and why the government had not done more to extinguish the fire.

In 1983, Congress allocated $42 million in funding to relocate Centralia residents to nearby towns. Only a handful of inhabitants now remain, having refused to move despite the land being claimed under eminent domain and many buildings bulldozed, leaving an eerie grid of roads that attract small numbers of tourists. Centralia continues to serve as an object of pop culture fascination, inspiring the setting of the horror film Silent Hill.

Yet the most surprising aspect of Centralia, Pennsylvania, is its ordinariness. Many examples of long-burning fires exist, both natural and man-made. The “Eternal Fire” in the middle of Iraq’s largest oil field, Baba Gurgur, may have been the basis of a number of Old Testament stories. The Door to Hell in Turkmenistan has been burning since Soviet engineers lit the natural gas field in 1971. Coal in Australia’s Burning Mountain has been lit for an estimated 6,000 years.

The Door to Hell in Turkmenistan. Photo Credit: Tormod Sandtorv

These examples are famous, but fires burn in coal mines, often underneath coal towns, across the United States and the world. Especially in China and India, which have many coal fires, efforts to fight the fires often pit men with shovels and bulldozers against inflamed mine shafts fueled by huge reserves of coal. In 2013, Tim Altares of Pennsylvania’s Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation told National Geographicthat Centralia is one of just “three dozen active mine fires in Pennsylvania.” A mine fire has been burning since 1915 in nearby Laurel Run, Pennsylvania, and while some residents relocated and others experienced adverse health effects, the town in still inhabited.

Gene Driscoll is a construction worker who lives in a mobile-home park near Laurel Run. To get there, he drives down an access road that often cracks or slumps from the underground fire. “I know if you’re from somewhere else, it seems strange, but to me it’s nothing unusual,” he told Smithsonian Magazine in 2005. “I’ve seen fires all my life. No one really worries about it.”

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.