Photo credit: Emmanuel Huybrechts

The question is not just whether justice is blind, but when it breaks for lunch.

In 2010, researchers Shai Danziger, Jonathan Levav, and Liora Avnaim-Pesso decided to test the legal adage that justice is “what the judge ate for breakfast.” The phrase is accredited to Jerome Frank, an American judge who once wrote in Courts on Trial that “because of overeating at lunch, [a judge] may be so somnolent in the afternoon court-session that he fails to hear an important item of testimony and so disregards it when deciding the case.”

Frank belonged to a school of thought called legal realism that sought to describe the law as it is rather than as it should be. It criticized the conventional image of the legal system as a logical machine, instead depicting the legal system as made of men and women influenced by politics, personal experience, competing morals, corruption, and personal biases. Judges and juries do not exhibit Spock-like commitments to impartiality; they miss key pieces of evidence during post-lunch food comas.

The three researchers from Columbia University and Ben Gurion University in Israel looked at the results of parole hearings to see whether the amount of time that had elapsed since the judges’ last break influenced their decisions. Rather than worry about food comas, they theorized that parole boards made worse decisions when they had not had a break recently.

To do so, Danziger and co. gathered data from 1,112 Israeli judicial rulings. In the majority of cases, a judge, assisted by a criminologist and a social worker, simply decided whether to grant or deny parole. The board made many decisions each day, and the data came from a ten-month period.

Their results, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences under the title “Extraneous Factors in Judicial Decisions,” strike a blow to the image of judges as impartial arbiters: Essentially, at the end of a long stretch of reviewing cases, the judges’ decision-making ability was as lousy as a kindergartener’s focus right before a snack break.

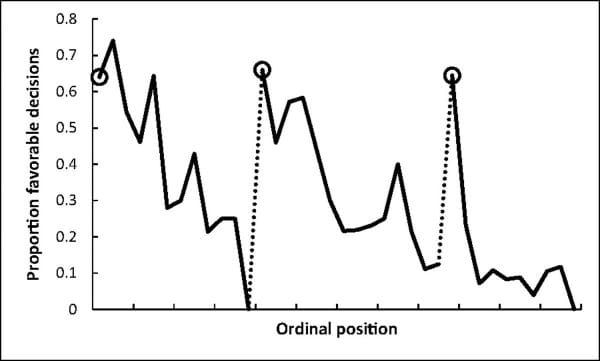

The Israeli judges studied by the researchers made decisions in three distinct periods broken up by a snack break and a lunch break. As the below graph shows, the odds of a judge granting prisoners parole reliably rose and fell depending on how long it had been since the judges’ last break.

The Impact of Breaks on Favorable Parole Decisions

Source: “Extraneous Factors in Judicial Decisions,” PNAS

Prisoners lucky enough to face the parole board when its members were well fed and rested had a roughly 65% chance of gaining parole. (Each circle in the graph represents a break; the x-axis shows time over the course of the day.) Yet over time, the odds of a favorable decision deteriorated until the last prisoner before a break had almost no chance of getting parole.

These results fit neatly into a growing strand of psychology that suggests that our willpower and decision-making abilities are like a muscle: they grow fatigued with use, but they can be restored by taking a break, eating a snack, or getting some sleep.

Focusing and making decisions leads to “decision fatigue.” This is why supermarkets stock the “impulse aisle” at checkout with candy — we’re so exhausted by deciding what to buy that we’ll grab some. It’s also why people so easily rack up wedding bills — after hours of debating flower arrangements and china designs, couples will just start saying OK to the default option. The judges (and the prisoners with the misfortune of appearing at the end of a session) fell victim to the same phenomenon; when tired by making decisions, the parole board went with the default option of denying bail and maintaining the status quo.

From one perspective, the researchers’ results are not shocking. A pithy way to sum up the study is that judges make poorer decisions when they are tired. But this is the type of effect people constantly underestimate. The data points in this study represent real prisoners, many of whom were returned to their cells while a prisoner with a similar case was granted parole an hour or two earlier.

The result is quite a piece of ammunition for legal realism. An ethic of impartiality and professionalism is nice. But the judges in the researchers’ study were very professional — the other major variables that affected parole decisions were whether the prisoner had a place in a rehabilitation program and whether he or she was prone to recidivism, and no racial bias was detected. Yet when you consider that many psychological biases operate around factors like class and race, crafting impartial laws (a difficult feat in itself) and then leaving them to be implemented by flawed, partial humans can seem criminally negligent.

After the publication of the paper, Jonathan Levav, who co-led the study, said:

“There are no checks about the judges’ decisions because no one has ever documented this tendency before. Needless to say, I would expect there to be something put into place after this.”

Eight months after the publication of the paper by Danziger, Levav, and Avnaim-Pesso, the Israeli review boards had not changed their policy. It seems Levav and his colleagues may be waiting a long time.

The judicial system, however, may have had good reason for not changing its procedure. In a response letter published in PNAS, Keren Weinshall-Margela of the Israeli Courts Research Division and John Shapard of the Federal Judicial Center in Washington make the case that mundane factors explain why prisoners fared so much better before the parole board right after a break. Does justice not get as grumpy as the study suggests?

In their paper, Danziger and Levav reject potential alternative explanations for their findings, including some sort of bias in the ordering of the cases. Shapard and Weinshall-Margela, however, contend that they missed several factors. They write that the parole board, which makes decisions for inmates from several prisons, tries to get through one prison before the next break. In each session, prisoners that don’t have a lawyer go last — and prisoners without counsel are denied parole about 20% more often. (The authors do not discuss the legal or moral implications of this.)

In addition, lawyers commonly represent multiple defendants, and when they do, they can present their cases in any order they want. The authors of the letter, who did not collect data but did conduct interviews, say that they suspect the lawyers presented their best cases first (those most likely to gain parole). The authors also note that the original paper fails to account for prisoners’ behavior behind bars — an important consideration in parole decisions.

So do judges and parole boards get too fatigued to do anything but maintain the status quo after several hours of hearing cases? Perhaps. The most striking aspect of the original study is the graph, which shows a very clear and dramatic trend. But very dramatic results can also indicate that something is wrong — that another factor is at work. In this case, it might be that the parole boards tend to hear the strongest cases first and the weakest last, which would make it no surprise that fewer prisoners win parole as the session wears on.

Justice is not completely blind, but in this case, it may not be as bad as we think.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.