Tournament. 1951 oil on canvas by Adolph Gottlieb.

The paintings shown in the 1958 exhibition “The New American Painting” are full of muddles of color and shapes ranging from representative to unrecognizable. The work of American Abstract Expressionists including Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning, the paintings inspired mockery and confusion from the public matched in intensity only by the appreciation they elicited from admirers.

President Truman commented, “If that’s art, then I’m a Hottentot.” Nevertheless, the Museum of Modern Art, which organized the exhibition and its tour through European capitals, noted that the artists’ style “is now dominant throughout the United States.” The exhibition’s press release identified as a source of controversy the fact that the painters, “as a matter of principle, do nothing deliberately in their work to make ‘communication’ easy.”

But one patron of the exhibit — the Central Intelligence Agency — hoped that the exhibit would have a very clear message. As the covert provider of much of the funding necessary to send the paintings on their tour of European capitals, the Agency intended to impress European intellectuals and shake up the stereotype of America as a cultural backwater. The goal was to win European hearts and minds; the stakes were victory in the Cold War.

Modern art was merely one campaign in the cultural cold war. The CIA covertly subsidized a European tour for the Boston Symphony that established it as world class, sent prominent American authors on book tours, and, most importantly, funded books, conferences, and magazines of arts and letters that took a critical stance on the Soviet Union. Many European intellectuals admired communism and looked to Moscow as an example. The CIA decided it needed to win over Europe’s “educated and cultured classes” to prevent communist revolutions from sweeping Western Europe.

The CIA’s two decade patronage of arts and letters represents a time when people saw culture as a powerful force in politics. It also speaks to an irony in America’s relationship with this type of “cultural diplomacy”: The only way to fund such inoffensive programs as cultural exchanges and intellectual conferences — at least on a large scale and with serious intent — was to fund it as covertly as the coups and assassinations for which the CIA became infamous.

The God That Failed

In 1949, the book The God That Failed brought together six prominent, former communist intellectuals from the United States and Europe. In six essays previously published in a U.S. government sponsored magazine, they described the actions of the Soviet Union — the “necessary lies,” Stalin’s purges, the stifling of intellectual freedom — that led them to turn against communism, the cause that they had believed in with religious fervor.

It was a disillusioning experience that the CIA hoped to see spread in Europe, where many intellectuals celebrated communism as a cause celebre. But the Agency faced an uphill battle, as the Soviet Union had an early lead in wooing Europe’s intelligentsia. The Communist Party had long sought influence abroad by supporting labor and student groups. In contrast, the United States, with its culture of isolationism and separation of art and state, had no Ministry of Culture or Ministry of Information dedicated to shaping its image abroad or promoting its arts.

World War II had hardly ended when American and European intellectuals began attending Soviet sponsored conferences that called for peace between the United States and the USSR and decried American warmongering. The United States had just announced the Truman Doctrine, intervening in Greece and Turkey against their communist parties, Winston Churchill had made his Iron Curtain speech, and a military alliance against the USSR had been formed in NATO. At such a peace conference in New York City’s Waldorf hotel in 1949, American, European, and Russian intellectuals and artists referred to Western forces as “new Fascists” and stated that “the present policies of the American Government will lead inevitably into a third world war.”

Melvin Lasky, a literary-minded anti-Stalinist who served as an American combat historian during World War II, described the Soviet propaganda effort against the US:

… the alleged economic selfishness of the USA (Uncle Sam as Shylock); its alleged deep political reaction (a “mercenary capitalistic press,” etc.); its alleged cultural waywardness (the “jazz and swing mania”, radio advertisements, Hollywood “inanities”, “cheese-cake and leg-art”); its alleged moral hypocrisy (the Negro question, sharecroppers, Okies); etc. etc …

The struggle to, in Lasky’s words, “win the educated and cultured classes — which, in the long run, provide moral and political leadership in the community,” involved political debate over Marx’s theories and the question of whether the United States or the Soviet Union was the aggressor. But it also had a strong cultural component. Which side had the culture emblematic of a global model? Did America’s racial and economic inequalities mean that it did not practice the democratic model it preached? What about the Soviets’ purges?

In the perceptions battle with the Soviet Union, America suffered from an image problem as a materialistic, cultural wasteland. As the American Director of Education and Cultural Relations in postwar Berlin noted, “Our culture is regarded as materialistic and frequently one will hear the comment, ‘We have the skill, the brains, and you have the money.”‘ To win over Europe’s educated class, the Soviets and Americans fought to exert cultural dominance. In the words of Frances Saunders, author of The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, “The cultural Cold War was on.”

From Berlin to the World

Beginning in broke, war torn Berlin, the Soviets and Americans battled to show the Germans their cultural prowess. In 1945, the Soviets’ State Opera began performing works with “anti-fascist” interpretations (a slight directed at the Americans). Several years later, the USSR opened a cultural institution that a British cultural affairs officer described as “most luxuriously appointed — good furniture, much of it antique, carpets in every room…” and able to “counteract the generally accepted idea here that the Russians are uncivilized.”

In response, the American occupying authorities renovated their own reading rooms and information centers, shipped in American performers for tours, and translated and distributed American novels and nonfiction. One satisfied administrator in postwar Berlin wrote that the cultural programs, “make a deep and profound impression upon those circles in Germany which for generations have thought of America as culturally backward and who have condemned the whole for the faults of a few parts.”

While the American occupying authorities in Berlin began the cultural Cold War in earnest, going so far as to expedite the clearing of German artists of all wartime wrongdoing so that they could contribute to the culture war, no one had the responsibility of fighting the culture war outside Germany.

Efforts by the State Department to play such a role backfired. In 1947, for example, it promoted an exhibition similar to “The New American Painting” called “Advancing American Art.” As The Independent reports, the State Department cancelled the tour after President Truman disparaged the abstract paintings and a congressman stated publicly, “I am just a dumb American who pays taxes for this kind of trash.”

Even more problematic, the exact type of European allies whose help the United States needed in the fight against communism were untouchable. Like the authors of The God That Failed, they were former communists or at least very left-wing. WIth Joseph McCarthy leading witch hunts to find communist sympathizers in the Federal government, no Congress would approve funding conferences of European lefties. And as the CIA archives note today, “Truman administration officials were not exactly looking for motley bands of former Communists to sponsor at a time when the White House was already taking flak at home for being soft on Communism.”

The Central Intelligence Agency, on the other hand, could act with limited Congressional oversight. At the time, the Central Intelligence Agency was being created out of the Office of Strategic Services, which had been created for World War II.

Intelligence officers noted the actions of an independent group called Americans for Intellectual Freedom that disrupted the Soviet peace conference in New York with sharp questions and counter demonstrations. They decided to fund a challenge to the next Soviet conference in Paris. Sixteen thousand dollars taken from Marshall Plan funds and funnelled through a French newspaper critical of the USSR paid the travel expenses of outspoken anti-Communists to compete with the Soviet peace conference with a “International Day of Resistance to Dictatorship and War.”

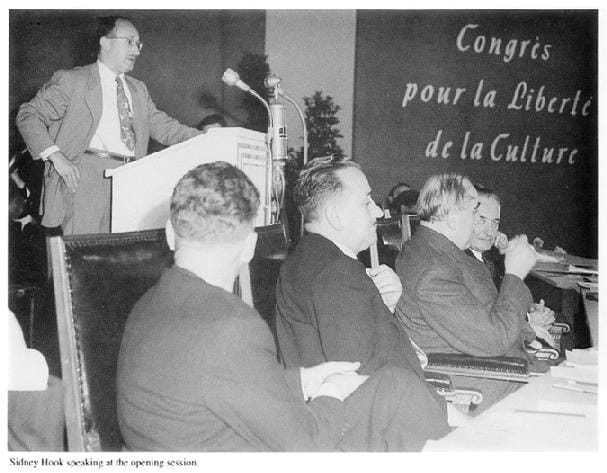

The idea inspired a number of anti-Communists, including several working as cultural officers in Berlin. A year later, in 1950, the CIA funded the “Congress for Cultural Freedom,” a conference in West Berlin which sought to counter the idea that “liberal democracy was less compatible with culture than communism.” Although not the agency’s creation, the CIA paid for travel arrangements and expenses through the State Department and private foundations and several leaders were part of the U.S. government. After the Congress ended, CIA largess enabled it to become a permanent cultural organization.

The CIA’s covert funding, limited oversight, and plausible deniability for politicians would soon be used to overthrow governments and fight proxy wars, but first it would be used to promote American culture and fund conferences of European intellectuals.

The opening session of the Congress for Cultural Freedom

For the next two decades, in conferences and in its magazine of arts and letters, Encounter, the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) expounded on the views expressed in the “Freedom Manifesto” created during its first meeting. It also played a chief role in funding the anti-Communist message and exhibiting American culture. Covert CIA funding passed through the CCF subsidized publications similar to Encounter throughout Europe and the world; the translation, publication, and distribution of relevant novels and books; American art exhibitions and musical performances abroad; and much more.

At the time, CIA culture did not clash with modern art and literary magazines. As related by American journalist George Plimpton, who worked as an editor at The Paris Review when it received covert American money, the CIA’s reputation did not turn away artists and liberals:

“This was right after the war. It was when the CIA was starting up. It was not into assassinations and all the ugly stuff yet. There were so many guys signing up for the CIA. It was kind of the thing to do.”

CIA officers were not conservatives pinching their noses as they funded modern art and pinko European intellectuals. They were part-time writers and appreciators of culture, often equal participants in the art world and leftist debates about communism. As journalist Peter Coleman wrote:

Now, at a unique historical moment, there developed a convergence, almost to a point of identity, between the assessments and agenda of the ‘NCL’ [Non-Communist Left] intellectuals and the combination of Ivy League, anglophile, liberal can-do gentlemen, academics and idealists who constituted the new CIA.

Today, writers and historians have fun with the idea of the CIA wielding Jackson Pollock paintings and Mark Twain novels as “Cold War weapons.” But in the 1950s and 1960s, “cultural cold war” combatants took seriously the idea that culture was the bedrock of a global struggle.

Writing on the subject, journalist Joel Whitney offers the following description of the American Studies program at Yale, chaired by a professor involved with the CIA, by a dean to Yale’s president:

From such a study we will gain strength, both individually and as a nation … strength, which we need so badly in our time to face the changing, and in part, hostile world … This is an argument … for the establishment of a strong program of American Studies at Yale, which in many respects is our most native university … In the international scene it is clear that our government has not been too effective in blazoning to Europe and Asia, as a weapon in the “cold war” the merits of our way of thinking and living … Until we put more vigor and conviction into our own cause … it is not likely that we shall be able to convince the wavering peoples of the world that we have something infinitely better than Communism …

Playing the CIA’s Tune?

For over 15 years, the Congress for Cultural Freedom had a large staff, organized constant conferences and events, published or supported dozens of publications, and had offices in 35 countries — all supported by covert CIA funding. (The New York Times exposed the CIA funding in 1966, at which point the CCF’s influence and the CIA’s cultural efforts subsequently declined.) The CIA’s larger propaganda efforts could plant or influence stories in over 800 global publications. CIA agents joked that the culture and propaganda efforts were a jukebox: the CIA could make people around the world “play any tune” it wanted to hear.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the figures involved with the CCF or one of its publications included nearly every famous, non-communist thinker or artist: existential philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, mathematician Bertrand Russell, playwright Tennessee Williams, “Godfather of neoconservatism” Irving Kristol… Did all these figures really publish magazines and speak at conferences while following the diktats of American intelligence officers?

While the CIA paid the bills, organizations like the CCF received American funds with as little knowledge as the taxpayers providing them.

The chief means through which the CIA covertly funded the arts was by laundering money through wealthy, Western philanthropists. The CIA enlisted sympathetic millionaires like Nelson Rockefeller, swore them to secrecy, and then had them donate to large foundations like the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations on the agency’s behalf.

The money then streamed from the foundations to CCF and America’s champions throughout Europe. Rumors of funding from the U.S. government swirled. After all, in broke, postwar Europe, solid funding for literary magazines and intellectual conferences at five star hotels appeared with all the subtlety of modern weapons in an Afghan proxy war. Yet the beneficiaries could remain ignorant of the CIA’s involvement.

Reviewing The Cultural Cold War by Frances Saunders, who is critical of promoting democratic values and the arts through covert means, one observer notes that during the 15 years that the CCF published the magazine Encounter with CIA funding, Saunders finds only one case of potential CIA censorship: “when an Encounter article by Macdonald was spiked in 1958 because of ‘its anti-Americanism.’’’

Instead of making demands, the CIA seemed content to amplify the voices supportive of the United States — and accept some criticism as the cost of doing business. In the war of ideas, the flow of money supported opinions in line with American interests more than those who were critical. Magazines and journals, for example, found a profitable line of business reselling interviews to the CCF from writers and thinkers critical of communism — but not interviews critical of America’s treatment of African-Americans. Similarly, books critical of communism received mass orders. In addition, a number of CIA agents or friends worked at the Congress and its publications, meaning a slant towards its editorial stance. But the magazines still published criticisms of racism in America and performances by black musicians (funded with CIA money) still inspired discussion of injustices.

Whether it was promoting the work of an American artist, organizing an anti-communism conference, or the dirty business of smearing a poet with communists leanings nominated for the nobel prize, it seems the CIA primarily supported those already working in line with its aims.

After the Cultural Cold War

America’s cultural war waned after the revelations of the CIA’s role in the late sixties. Interest waxed once again after September 11, when diplomats and foreign affairs types began to speak earnestly of “public diplomacy” — cultural/education programs and information policy. Or, as it’s sometimes catchphrased, “telling America’s story to the world.”

In the Middle East and North Africa, America once again saw a world view advocated that was incompatible with its existence and a rejection of democratic values at least partially linked to characterizations of the United States as materialistic, culturally shallow or depraved, and hypocritical. And once again, the U.S. seemed to be missing from the conversation. “There’s a worldwide debate about the relationship between Islam and the West,” one American official opined. “And we don’t have a seat at that table.”

Foreign policy experts talked up soft power — the ability to establish preferences and norms “associated with intangible power resources such as culture, ideology, and institutions” — and advocated for more funds and attention to public diplomacy as a way to exert it. They were calling for the same belief in the power of culture and ideas that motivated the cultural Cold War.

Today American diplomats run exchange programs for promising foreign students and organize performances by American artists. The U.S. Government-run Voice of America broadcasts news around the world. Archeologists partner with foreign counterparts in sponsored cultural preservation projects.

But public diplomacy did not get the priority its advocates hoped. A 2005 report states:

After the Cold War, when cultural diplomacy ceased to be a priority, funding for its programs fell dramatically. Since 1993, budgets have fallen by nearly 30%, staff has been cut by about 30% overseas and 20% in the U.S., and dozens of cultural centers, libraries and branch posts have been closed.

In 1999, an official cultural diplomacy policy was the casualty of bureaucratic adjustments. That remains the case today.

Of course, despite the advocates’ belief in the value of public diplomacy, it’s not a silver bullet for America’s image problem. While the CIA touts the Congress for Cultural Freedom as “widely considered one of the CIA’s more daring and effective Cold War covert operations,” most observers note the difficulty in trying to draw any conclusions about its effectiveness. And actions speak louder than words, something comically shown when CIA funding helped send an American poet on a tour in South America to improve the country’s image — tarnished by the CIA backed coup of Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz. The recent news that the State Department spent over $600,000 buying Facebook Likes also provides reason to question how the department is spending the budget it currently has for public diplomacy.

But every day, the United States is the subject of vitriol (both deserved and undeserved) in foreign news reports, talk shows, and blog posts. It shapes perceptions of America around the world and is the first draft of history for those watching, reading, and listening. It’s rarely a welcoming scene. But what’s surprising is that the United States hasn’t prioritized being part of that debate since the CIA clandestinely took charge of the cultural Cold War.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.