In March 2010, years before Ferguson, Missouri, became known for sparking the Black Lives Matter movement, the city’s Finance Director contacted the Chief of Police with a solution to the city’s budget problems.

The Finance Director wanted the police to generate more revenues from fines — money paid for infractions like traffic violations and missing court appointments. He warned that the city would be in financial trouble “unless ticket writing ramps up significantly before the end of the year.” “Given that we are looking at a substantial sales tax shortfall,” he wrote, “it’s not an insignificant issue.”

The Finance Director’s request surfaced as part of the U.S. Department of Justice’s investigation of the Ferguson Police Department. The investigation was instigated by the civil unrest that followed the fatal shooting of an 18-year-old African American man named Michael Brown in August 2014. Its goal was to better understand why the citizens of Ferguson felt so at odds with the police department chartered to protect them.

The Justice Department concluded that the mistrust between the police and the community primarily resulted from excessive fining. “Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs,” the report read. The use of fines to fund the government undermined “law enforcement legitimacy among African Americans in particular.”

Ferguson has a population of just over 20,000 that is 67% African American, and it raised over $2 million from fines and fees in 2012. This accounted for around 13% of all government revenue, and a disproportionate amount of this money came from the African American population.

Is Ferguson an anomaly?

Using the U.S. Census’s Survey of Local and State Finances, we investigated the proportion of revenues that cities typically receive from fines, as well as the characteristics of cities that rely on fines the most. What are these cities like? Are they rich or poor? In certain parts of the country? Heavily Black or White?

We found one demographic that was most characteristic of cities that levy large amounts of fines on their citizens: a large African American population. Among the fifty cities with the highest proportion of revenues from fines, the median size of the African American population—on a percentage basis—is more than five times greater than the national median.

Surprisingly, we found that income had very little connection to cities’ reliance on fines as a revenue source. Municipalities that are overwhelming White and non-Hispanic do not exhibit as much excessive fining, even if they are poor.

Our analysis indicates that the use of fines as a source of revenue is not a socioeconomic problem, but a racial one. The cities most likely to exploit residents for fine revenue are those with the most African Americans.

Every five years, the government collects data on the revenues and expenditures of all state and local governments. This census includes nearly 20,000 municipalities – municipalities are the formal name for what we think of as towns and cities.

The vast majority of municipal revenues come from a combination of property, sales and income taxes, as well as intergovernmental transfers like grants given by the state or federal government to maintain a highway.

Municipalities also generate revenue from Fines and Forfeits, which are defined by the Census as the following:

“Receipts from penalties imposed for violations of law; civil penalties (e.g., for violating court orders); court fees if levied upon conviction of a crime or violation; court-ordered restitutions to crime victims where government actually collects the monies; and forfeits of deposits held for performance guarantees or against loss or damage (such as forfeited bail and collateral).”

A large portion of these Fines and Forfeits are for parking infractions, traffic tickets, and fines for missed court appearances.

According to the White House, revenues from fines have increased across the United States. For most municipalities, however, they still make up only a tiny portion of municipal revenues. Of the nearly 4,600 municipalities with over 5,000 people, the median municipality received just 0.9% of its revenues from such payments.

But for a minority of municipalities, fines account for a significant share of revenues. In 2012, 4.8% of municipalities with over 5,000 people received 5% or more of their revenues from fines, and 38 municipalities received 10% or more.

Ferguson, Missouri, was one of these 38 cities.

The following table compares the demographics of the median municipality in the United States and the median municipality that ranks in the top 50 in terms of fines as a proportion of revenue. Demographic data is from the 2012 Five-Year American Community Survey. For this table and the rest of our analysis, we only include municipalities with 5,000 or more individuals.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Survey of State and Local Finances

By far the largest difference between the median city and cities that receive substantial revenues from fines is the size of the African American—and, to a lesser extent, Hispanic—population. (Whites and African Americans may also be Hispanic.)

African Americans make up less than 4% of the population in the median municipality. But in the 50 cities with the highest proportion of revenues from fines, African Americans make up nearly 19% of the population. This is a difference of 15%, which is mirrored by the 14% lower proportion of Whites in cities with substantial fine revenue. If we look at averages rather than medians, a similar pattern emerges.

The relationship between fine revenues and the size of a municipality’s African American population applies in less extreme cases as well. The following chart shows the relationship between larger African American populations and larger fine revenues.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Survey of State and Local Finances

Because the African American population has a higher poverty rate and lower median incomes than the national average, one might expect a correlation between poverty levels and revenues from fines. If this were the case, it would be unclear whether excessive fining is a racial problem or a socioeconomic one. But the data suggests that this is not so.

The cities that derive substantial revenues from fines are only slightly poorer than average. The proportion of impoverished people in the median top 50 city in terms of fines is 14.5%, and the median income is $49,600. These are relatively close to the 14.2% poverty rate and $48,300 median income of the median city.

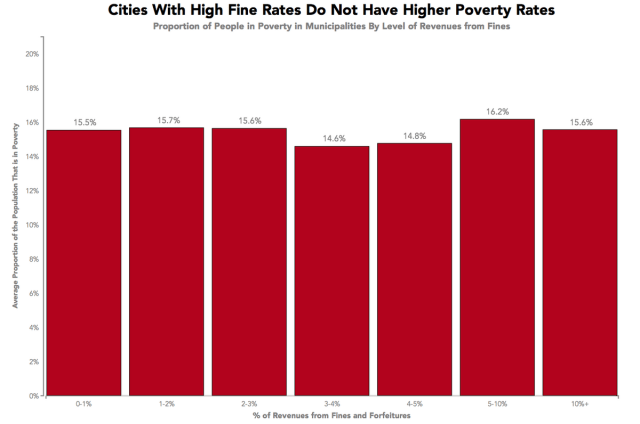

The chart below further demonstrates this lack of relationship between poverty and revenues from fines. It has the same design as the above chart, but it displays poverty rates rather than the African American population.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Survey of State and Local Finances

The poverty rate is almost the exactly same in municipalities that generate 0-1% of their revenues from fines as those that receive over 10%. The median income in cities with more than 10% of their revenues from fines is actually higher than those that receive 0-1%.

We had expected to find a relationship between revenues from fines and income levels, so we conducted additional checks.

We examined the approximately 1,200 municipalities that were over 90% White and less than 10% Hispanic. Again, the rate of poverty and incomes for municipalities with high and low fine rates did not diverge. Poverty cannot explain our results.

***

Many municipalities that greatly rely on fines and forfeits for revenue have an unusually large African American population. But not all of them do. Race does not fully explain why certain cities use fines to fund the government.

The plot below displays a point for every municipality with over 5,000 people. The percentage of revenues from fines is on the x-axis, and the percentage of the population that is African American is on the y-axis (including a regression line that displays the trend). The chart shows that though the correlation is strong, it is not inevitable that a municipality with a large African American population will have an unusually high proportion of revenues from fines.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Survey of State and Local Finances

Of the top 100 municipalities in terms of revenues from fines, more than two thirds are in just six states: Texas (19), Georgia (17), Missouri (12), Illinois (9), Maryland (6) and New York (6).

The Southern states, where the African American population is largest on a percentage basis, are overrepresented on this list. But the relationship between fines and the African American population is not a Southern phenomenon. In states like Maryland, Missouri and New York, municipalities with large African American populations are more likely to have an unusually high amount of revenues from fines, even after accounting for poverty rates.

The chart below lists these 100 fine-heavy municipalities along with their demographic profile.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Survey of State and Local Finances

***

It seems unlikely that the connection between fines and large African American populations—a connection that cannot be explained by poverty—is the result of African Americans across the United States committing more finable offenses.

A more likely explanation is that they are more highly policed and that, as has been acknowledged by the Director of the FBI, African Americans suffer from heavier legal penalties due to the implicit bias of police officers.

Charging individuals with minor infractions is highly discretionary and influenced by where law enforcement choose to direct their attention. Although African Americans and Whites report smoking marijuana at the same rates, African Americans are 3.7 times more likely get arrested for marijuana possession.

Other research shows that while African Americans are less likely to sell drugs than Whites, they are more likely to be arrested for it. An analysis of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 6.6% of White people between the ages of 12 and 25 have sold drugs compared to 5.0% of Blacks. Yet Black people are 3.6 times more likely get arrested for selling drugs.

Given this evidence, it seems likely that police officers often fine African Americans at higher rates, even if Black people do not commit more infractions.

***

In its report on Ferguson, the Department of Justice provides examples of the suffering caused by the police treating people as “potential offenders and sources of revenue” rather than as citizens to protect. These anecdotes include the story of a 32-year-old African American sitting in his car and “cooling off” after playing basketball who received tickets for not wearing his seatbelt, falsely declaring his name as “Mike” instead of “Michael” and having an expired driver’s license. He lost his job as a result of the charges.

A variety of reporting suggests that such incidents are not exclusive to Ferguson. They may also be illegal.

According to the Harvard Law Review, government schemes that raise revenue through policing violate three provisions of the Constitution: “the Due Process Clause, which requires neutral administration of criminal law; the Equal Protection Clause, which bans discriminatory punishment; and the Eighth Amendment, which forbids excessive fines.” The Law Review article concludes, “Coupling discretionary police power with an ability to raise revenue amplifies the pathologies that are perverting modern criminal justice.”

***

Our findings are a reminder that the frequently strained relationship between the African American community and law enforcement is not just a result of high profile police shootings. They also result from the way minor infractions are exploited for government revenue in African American communities.

This analysis is a jumping off point. The various kinds of fines and forfeitures, which include everything from court fees to traffic violations, are lumped together in the Survey of State and Local Finances. To gain a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, it is important to split out the different ways citizens are fined and identify those infractions that people are most likely to be charged with. Many researchers and reporters are doing this on the local level.

When we began this analysis, we expected that fines would be correlated with income levels—and that places with poor populations would disproportionately levy fines. But that’s not what we found. Some rich cities use punitive fines for revenue, and some poor ones do too.

The best indicator that a government will levy an excessive amount of fines is if its citizens are Black.

Our next article explores why some athletes say they use cannabis for athletic purposes. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Want to write for Priceonomics? We are looking for freelance contributors.