This post is adapted from the blog of Flexport, a Priceonomics customer

When you board a plane, you never know what’s beneath your feet.

Travelers hate checked bag fees, but shipping companies pay for space in planes’ cargo holds every day. As passengers board, baggage handlers throw suitcases into the plane’s lower deck. They also pack the cargo hold with packages being sent as freight. Depending on the flight, a plane’s cargo may include iPhones, U.S. Postal Service mail, or live oysters bound for a Manhattan bar.

Less than 1% of world trade goes through the air, but in financial terms, that one percent represents 35% of global trade. Cargo sent by plane is small and either expensive or time-sensitive: iPhones, Valentine’s Day roses, and premiere wines fly; grain, t-shirts, and cars get trucked or put on container ships. Globally, airlines make 9% of their revenues from cargo, and other shipping companies (Fedex and UPS in the United States) fly planes devoted exclusively to cargo.

This is why those hated baggage fees make sense. Space in the cargo hold is valuable to airlines, and passenger bags, which receive priority over other packages, can bump cargo from a flight and cost airlines money.

This, at least, is how airlines spin baggage fees and getting rid of free meals: they claim they have responded to travelers’ desire for low fares by unbundling, which means charging for things that used to be included in the cost of a ticket. The easiest way to make fares cheaper is to have it cover nothing more than the cost of putting a butt in a seat. So if you want to enjoy a drink or check a bag, you have to pay.

But if we are paying for something once included in the ticket price, are we getting a good deal?

The Case for Checked Bag Fees

On domestic flights in the United States, airlines generally charge $25 to check a bag and $35 to check a second bag. The most common weight limit for each checked bag is 50 pounds.

So how do baggage fees compare to the price charged to freight companies for 50 pounds of cargo?

In the freight business, airlines charge more or less depending on the route. It costs more to ship a package from New York to Alaska than from New York to California. But as the below chart shows, for almost every flight, baggage fees are low compared to cargo prices.

This chart uses data from World ACD for the 50 routes responsible for the most cargo shipments, which overlaps imperfectly with the busiest passenger routes. Shipping rates differ depending on direction, so we averaged the cost of each leg. The most expensive route for cargo from this group is Sacramento–Anchorage and the least expensive is San Francisco–Atlanta. You can find a full list of airport codes here.

These prices are for express cargo, which is similar to first class mail: It’s more expensive, because if a plane can’t take all the cargo, express cargo has the highest priority after passenger bags. This makes it the closest comparison to a checked suitcase.

This data comes with a few disclaimers. The rates are annual averages—even though rates increase at busy times like Christmas. The data also does not differentiate between airlines, and it includes data from both passenger and cargo-only airlines.

Still, when airlines check your suitcase for $25, they are providing a service for which freight companies pay from $40 to $100.

This analysis may overstate the airlines’ case, however, given that their planes primarily serve passengers. Should passengers really have to pay express rates to be sure that their bag flies on the same flight as them?

Another way to figure out whether checked bag fees are a good deal is to look at how much revenue an airline misses out on when it puts your suitcase in the cargo hold—instead of taking cargo from a shipping company.

The best way to do this is to compare checked bag fees to the cost of shipping packages at the standard, regular rate. Unlike express cargo, regular cargo is low priority. So when a plane’s lower deck does not have enough space, it is the regular freight that gets left behind. In these cases, airlines lose out on the revenue from the regular cargo whose spot your suitcase took.

Even with this tougher comparison though, airline baggage fees look reasonable. On the majority of routes, airlines charge less for a suitcase ($25 or $35) than they could make by instead shipping a package (at the regular, low-priority rate) of the same size ($23 to $70).

Shipping rates are higher between many small airports, which makes a checked bag an even better deal when you fly between small airports: Shipping 50 pounds of regular cargo from Richmond to Albuquerque earns airlines $54, from Albany to Kansas City earns $74, and from Louisville to Huntsville earns $125.

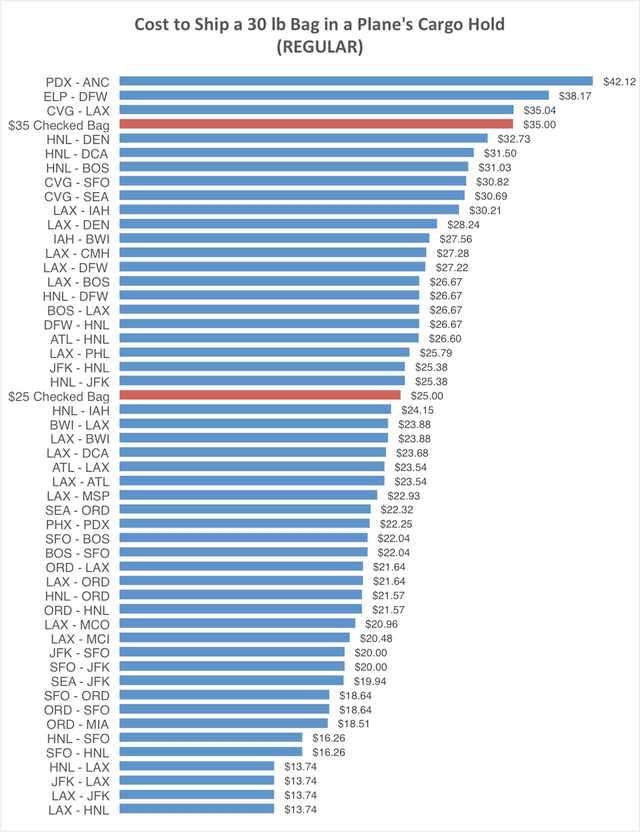

But what if your suitcase doesn’t weigh exactly 50 pounds? What if you check a 30 pound suitcase? In that case, the checked bag fee does not look as generous.

When we compare baggage fees with the cost of shipping 30 pounds of cargo, more than half of passengers on major routes overpay on a $25 fee, and almost everyone overpays on a $35 fee. Passengers flying between small airports still get a better deal, but this is why, overall, airlines are profiting nicely from baggage fees.

“In our analysis of passenger airlines,” says Robert Dahl, Managing Director of Air Cargo Management Group, “we found that airlines make three times more revenue from baggage fees than from cargo in the US domestic market.”

“The revenue per pound is much higher for luggage than cargo.”

Why Aren’t There Baggage Fees for International Flights?

If you fly from China to New York, you are following one of the world’s largest trade routes. The cargo hold will be packed, and if you check a 50 pound bag, it means the airline can’t charge a freight forwarder around $265 to ship a 50 pound package.

On flights within the United States, however, airlines have plenty of space. Most flights may be overbooked, but your checked bags have legroom. The average domestic flight only fills 37% of its cargo hold. This means that the situation described above—where your checked bag forces the airline to leave cargo behind and lose out on the revenue from that cargo—is a rare occurrence.

Planes fly around America with empty bellies for a few reasons. One, according to Robert Dahl of Air Cargo Management Group, is that airlines “make money by having their airplanes in the air.” Their priority is spending as little time as possible at the gate, so they don’t want to wait for cargo—which is not as valuable as passengers—to be loaded.

Another factor is that domestic planes are narrow and inefficient for cargo. Baggage handlers have to load cargo by hand—the same way you see them throwing suitcases into the hold as you board—which is slow and limits the size of packages that passenger airlines can accept. For this reason, most domestic air freight is shipped in Fedex and UPS planes, which have wide cargo doors and conveyor belts.

A cargo plane is loaded from the front. Photo by Tak.

The main reason, though, that domestic flights do not fill up with cargo is America’s highway and rail system. Trucks and trains can take packages cross country more economically; freight companies only need planes for exceptional cases like overnight delivery, and that is the domain of Fedex and UPS. As a result, Dahl says, “in the lower 48 states, only in very rare instances are passenger bags bumping freight.”

This means that airlines have the incentives of baggage fees backward.

Most international flights allow travelers at least one free checked bag. This makes perfect sense from a customer service perspective. But it makes no sense from an economic perspective, because on most international flights, each checked bag displaces wine from France, iPhones from China, or fruit from Latin America.

Instead airlines charge for checked bags on domestic flights, which incentivizes customers to carry on their bags and fight for space in cramped overhead bins—even though the cargo hold is empty. This is annoying, and it may hurt airlines’ bottom line. Airlines have ordered new planes with larger overhead compartments to accommodate extra carryons. The inevitable need to check bags once the bins fill up also delays flights.

***

Not everyone pays baggage fees. First and business class passengers, frequent flyers, and customers with the airline’s credit card can check bags for free. Much like banks that nickel and dime customers with low balances, airlines have decided to charge fees to increase the margins on their least financially valuable customers.

Those nickels and dimes have added up. The rise of fees for checked bags, ticket exchanges, and reserved seats has produced a mostly new, $38 billion revenue stream for airlines that is as much as 80% profit. Of that, $3.1 billion came from domestic checked bag fees. Southwest is the last major holdout, and its investors are clamoring for the airline to start charging bag fees.

The logic and incentives of checked bag fees are all wrong. But for now, airlines see the practice as too lucrative to give up.