Young Rock Band Land rockers “The Psycho Penguins”

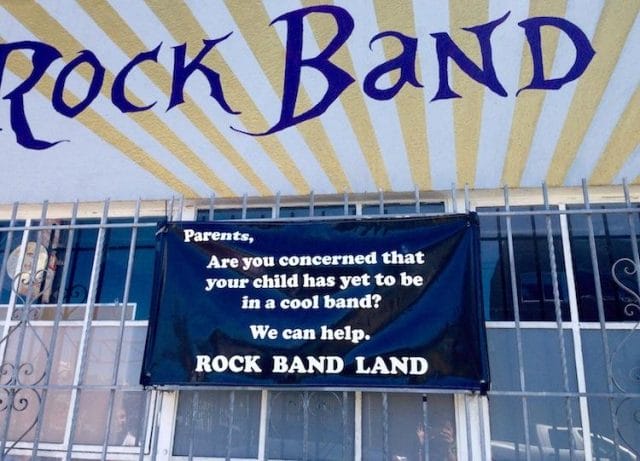

On 17th Street in San Francisco’s Mission District, sandwiched between an artisanal leather shop and a cavernous old police station, sits a building with this banner on the front:

Are you concerned that your child has yet to be in a cool band? We can help.

Welcome to Rock Band Land — Brian Gorman and Marcus Stoesz’s school for young rockers. “Young,” in this context means really young. When Gorman started the program, seven years ago, he was just working with preschoolers. Now he and Stoesz coach kids ages 4 to 12.

At many other rock ‘n’ roll schools for kids, the students are usually slightly older, and the focus is on learning to play classic rock covers like professional classic rock cover bands. At Rock Band Land students are lead through the process of original songwriting and musical collaboration. In the summer session Gorman, Stoesz and their band of students collaboratively write, record, and perform a new, original song every week.

That’s a rate of production that would make many adult rock bands balk. When Rock Band Land released its first full-length album last year, they had a lot of songs to choose from: 150 to be exact. Now there are 207. Many of those songs, written with children, are tremendously weird. The song the group wrote last week, “The Cockroach’s Revenge”, is about a vengeful cockroach (Jojohn Cockroachian) who turns people into sausages and sells them. It’s surprisingly catchy.

Or maybe that isn’t so surprising. Gorman and Stoesz are accomplished musicians in their own right, veterans of the Bay Area indie rock scene, as are many of the other adults who make Rock Band Land tick. Rock Band Land is their latest artistic challenge, and inspiration. It’s also their attempt to coach kids through lessons — both musical and not — that they learned the hard way. One of the most important lessons: be cool.

Brian the Fire Breathing Monster

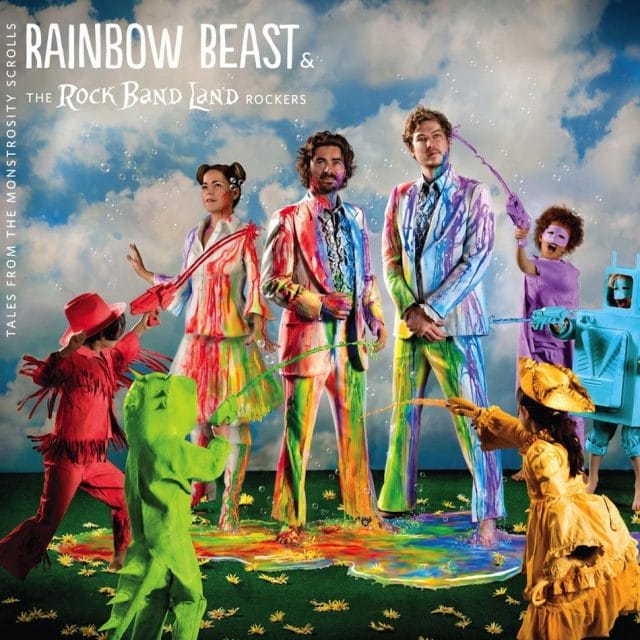

Rock Band Land’s debut album was under consideration for a Grammy. Gorman’s the one with the beard, center. (Bandcamp)

Brian Gorman is a drummer. He wears his hair in a dark ponytail and has a mottled brown beard, and his blue eyes are quick to brighten. His smile is easy and his repertoire of funny faces is vast. He’s energetic but gentle and he tells jokes that make both kids and parents laugh. It’s pretty clear that many of them think he is very, very cool.

“In Rock Band Land, we use ‘cool’ as a synonym for respect and creativity,” Gorman says. “It’s about engagement not aloofness. I absolutely wish I had a place like Rock Band Land as a kid. It would have saved me countless years of trying to ‘be cool’ — when I was overly concerned with others’ opinions, and thought breaking things was great fun.”

Originally from New York, Gorman said that he had a hard time as a teenager until a few “amazing” teachers “saved my life”, when they saw his potential as an artist. “They encouraged me to use my powers for good and not for evil,” he says. “I began to feel like a person and not a fire-breathing monster.”

He didn’t start playing the drums until his 20s, when he was living in Japan. His first gigs were as a street musician. “I had a band of total weirdos,” he says, “and we’d write and try to play songs that were way beyond our abilities.”

Then he headed to San Francisco and spent a decade hustling as a rock drummer. Now, he’s 40, and he’s picked up some serious chops along the way. In 2004, he formed his current band, Tartufi. In a review of their most recent album, NME wrote of the music, “Imagine Animal Collective boxing their way out of rock’s paper bag without putting down their guitars first and you have it […] Tartufi are just two but sound like 12. Drummer Brian Gorman must have arms like continents.”

In the late 2000s, Gorman was eking out an existence as an artist in the San Francisco Bay Area, where cost of living was already very expensive. On top of trying to hack it as a professional musician, he was teaching preschool. The flexibility of preschool was great. “I would go out on the road and come back and teach in between,” he explains. But there was a catch: the music of preschool was really getting to him.

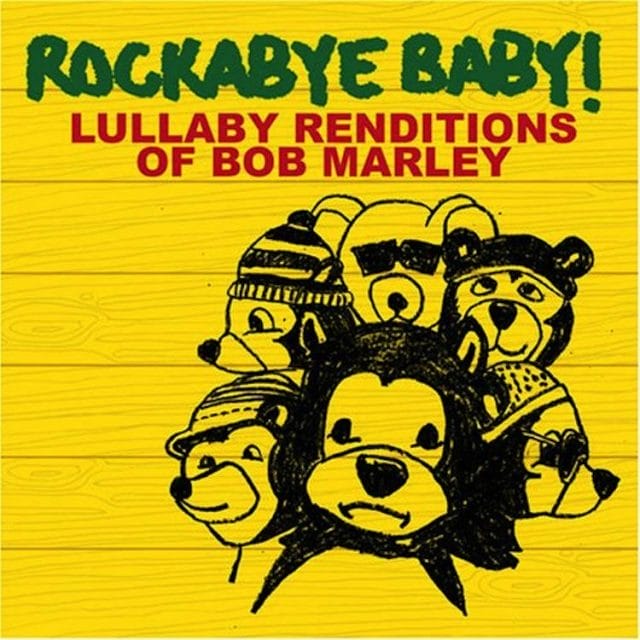

Bob Marley, for babies!

Songs from children’s television shows; “sanitized” versions of top 40 hits; nursery rhymes sung in the voice of a dramatically cheerful woman over synthesized glockenspiel. Most music made for children is easy to hate — each song like the musical equivalent of a tiny jar of baby “vegetable” puree. It goes down disconcertingly smooth and has very little taste. As a musician, nobody has ever disliked it quite like Gorman did, and still does.

“We had this CD bin of condescending, insulting, gross kid’s music,” Gorman seethes, remembering the soundtrack he had to work to. “It was just saccharine and not thoughtful.”

One day, he had a thought that would gradually alter the course of his life: Kids could make punk rock music.

“Punk songs are three chords, you can do it with kids,” Gorman explains. “You can do it with four year olds.”

First, he prototyped the idea — six of his preschool students joined an after school program he lead about pre-K rock & roll. It worked, in the sense that Gorman was happy with it, and so were kids and parents. Then he started a teaching a Saturday class, independently from the preschool, which quickly filled up and became two Saturday classes. After about a year of that, he started offering a “summer camp”, where kids would come for five all-day sessions.

That worked out well, too. Their clientele grew through word of mouth. San Francisco has no shortage of creative parents looking to nurture their children’s artistic side. But the school also retained a lot of kids who started young and then never left.

“We basically started adding in the days of the week during the year,” Gorman says. “Now we work seven days a week.”

Monday Funday

During the school year, the Rock Band Land process is spaced out over 6 weeks of after-school sessions. During the summer, six weeks are condensed into one intense routine.

On Monday at Rock Band Land summer camp, first, everybody meets — all 32 students enrolled in the summer program. Gorman estimates that on average about 60% of students (who he calls “rockers”) in any given class are Rock Band Land veterans. Some rockers, he says, re-enroll in the program continuously. Some of them have been doing so for years by now, and gotten really, really good at it.

The agenda for Monday is to gather all the materials for the song. The music comes first. One special room in Rock Band Land is “the rock out room,” a recording and rehearsal studio that houses a handful of child-sized electric guitars, bass guitars, and drum kits, along with keyboards and microphones. The students descend upon these instruments, (they put the most distortion on the pink guitars, to subtly encourage the younger boys to break gender norms), with Gorman and Stoesz around to help resolve conflicts. Then they noodle, working out musical “ideas” to share with the group.

Young rockers (Photo: Jorge Novoa & Kristin Sard)

This does not involve any formal musical instruction. Rock Band Land does offer private lessons, but only to rockers of a certain age or maturity level, and only if the rockers themselves display a persistent interest in learning to play the instrument. “We only offer lessons once the kid has been asking for an instrument all the time,” Gorman says. “If we sense that the request for lessons is coming from the parents and not the rockers, we almost always say no.”

As a consequence, on Monday mornings many kids don’t “know how” to play the instruments they’re playing with. They’re feeling them out intuitively. Many of their ideas are simple: a strumming pattern on an open-tuned guitar. A two-note riff on the keyboard. Some ideas can build on other ideas — a drum backing to a guitarist. The only requirements placed on an idea are: (1) it has to be original, not a blatantly recognizable phrase from another song, and (2) the rocker needs to be able to repeat it. “As soon as it repeats,” Gorman says, “it goes in the pile.”

Gorman’s partner Marcus Stoesz then takes that pile of melodies and chords and rhythms and Frankensteins it into an indie rock song. While he’s doing that Gorman is in another room with the kids, working on the lyrics and the story.

“The process has evolved quite a bit, but there was always a story component,” Gorman says. “I knew early we needed something to sing about. If the kids don’t care, it’s never gonna work.”

“All young children are enthralled with good stories,” he says, so that was a natural starting point. This brainstorming process involves a lot of wild and crazy ideas and non-sequiturs. “Part of our job is to be able to run with the randomness and then re-direct it back,” Gorman says. “Sometimes the kids are creative and they know it, and sometimes they’re creative but they don’t know it. When the group is good we can kind of go anywhere — it’s really wonderful.”

“Good” means creative, but it also means adhering to Four Rules of Rock Band Land:

I: Be original.

No phrases, characters, or plots directly lifted from movies or television or other people’s music. “I just want to challenge them to be more creative,” Gorman says. “I’d rather have them use their imaginations and go in their own place instead of where someone else is telling them to go.”

II: Don’t be mean.

Anything can happen in a story, including death. But even the darkest stories have to end on a note of redemption. “The dark can actually be kinda funny or exciting if you’re the author,” Gorman says. “But if you’re sharing it with other kids out of context those sorts of things can be really scary.”

III: No potty language.

“That’s just basically to be respectful,” Gorman says. “But also because once we start talking about pee and poop, all we do is laugh the whole time.”

IV: You can’t just say “no” to an idea: it’s your responsibility to adapt it.

The idea is to encourage compromise while maintaining ownership. It also helps Gorman look out for the quiet kids. If Gorman can tell one of the kids is uncomfortable with a vampire in a story, for example, he’ll help them adapt it into something they like: “What if they had pink skin instead of white skin? What if — dude! This vampire doesn’t drink blood! What does this vampire drink instead?”

Creative collaboration is a challenging task even for otherwise well-adjusted adults, but these rules are meant to be guidelines for making good art without destroying friendships. This process also slowly draws shyer kids out into participation and engagement. Gorman says his work has made him a better creative collaborator outside the classroom, too.

“Another big part of the value here,” Gorman says, “is just creating a space where it’s not only acceptable to have weird ideas, but where you’re celebrated for them. Our veterans will save jokes or ideas up for Rock Band Land. They know they can come here and say the craziest thing, and as long as they’re obeying our rules we’ll go with it.”

On Monday nights, Gorman and Stoesz put their words and music together into a song. Gorman makes abridges the story, and tweaks it to fit Stoesz’s music.

Stoesz and Gorman playing the children’s instruments (Photo: Jorge Novoa & Kristin Sard)

It helps that both Stoesz and Gorman are talented composers and performers, and almost preternaturally good at communicating with the children. Guitarist and vocalist Marcus Stoesz joined Rock Band Land six years ago, and Gorman says he was essential to the program’s flourishing: “He made it way better, honestly. It was a kernel of an idea that he poured oil on and helped explode, so we now have popcorn burning our faces.”

The two met as professional musicians on the road, and their bands toured together. When Stoesz’s old band broke down (“both physically and emotionally,” Stoesz says), he was looking to move to San Francisco, and Gorman was looking for a partner.

Most other artists Gorman had worked with didn’t have the teaching skills, or the right lifestyle, for the job. But Stoesz, who was 24 at the time, was something else. “He was just astounding,” Gorman says. “He was a prodigy, musically. And he had a background working with developmentally disabled children, like me. First I hired him as an employee and within like two months he became an equal partner.”

Stoesz, whose current band is a group called The Music Wrong, is a quieter, blonder complement to Gorman’s fire-breathing-monster. He grew up in Kansas and learned to play music in church. Then he went to school for music composition. Gorman says his spirit animal is an orca, and Stoesz’ is a panda. Through a strong friendship and “practicing what they preach,” they’ve developed a copacetic creative partnership, which is the only way they’ve been able to accomplish as much as they have.

“Early on we would kind of butt heads about things that we don’t even have to talk about now,” Gorman says. “We’ve come to a really wonderful place of mutual respect for our different skills.”

The Rest of the Week

On Tuesdays, Gorman and Stoesz present their draft of the song to the group. They point out which parts were contributed by which kids. “Once we’re done,” Gorman says, “there’s usually so much pride and excitement and ownership about the song that they’re super into it.”

Also on Tuesdays, they do a dramatic reading of the non-musical version of the story for the week. Gorman will, over the weekend, turn this story into a podcast as an explainer for parents, (and a reminder for the rockers), on what the song is about. It’s basically the most involved post-album approach to liner notes of all time.

On Wednesdays the rockers learn and rehearse their parts in the song. On Thursdays, they record. Gorman and Stoesz record a scratch track and the kids take turns singing over it. All 32 of them. Some of the instrumentalists get solos, and record those separately, too. The bar is pretty high, so this isn’t necessarily easy work. “Any song or story that leaves here is something that we would be happy to release on a record,” Gorman says.

On Fridays they perform, in two groups of 16. The parents pile into the rock out room, the kids with more delicate hearing wear protective headphones. The young rockers all stand at their instruments. Stoesz is near the front with a guitar and a mic, Gorman MCs and nestles in the back corner at a drum kit, where he can keep an eye on the drummers and encourage them to pick themselves back up when they lose focus. An adult bassist joins them — sometimes Jen Aldrich, a Rock Band Land mom and Bay Area indie veteran herself, who Gorman says has become “like a silent third partner.” She’s the bassist on their album, and the most business-savvy of the team.

This week’s song, “The Cockroach’s Revenge” about a cockroach who turns people into sausage, is very weird and very catchy. “Even better than last week’s,” the kids say, and Gorman and Stoesz agree. Everybody’s a little fidgety in anticipation. While the adult performers fiddle with the sound levels, the kids take turns telling jokes into their mics keep the audience entertained, which is itself an important rock and roll skill.

Then it’s showtime, colored lights flash, the 16 kids and three adults rock out, parents take videos. There’s no smoke and mirrors: you can hear everyone. A small-ish girl in the front alternates between two keys on her keyboard in time. A boy stage left plays eighth notes on the hi-hat. The kids know all the words and sing them together.

The “redemption” in “The Cockroach’s Revenge” comes when an inventor develops a “reverse” switch for the cockroach’s sausage machine, so that if you put sausages in, people come out. The switch is flipped and there’s an instrumental break. An eleven-year-old named Odin, who has been coming to Rock Band Land since he was five and is now incurably obsessed with electric guitar, proudly performs his solo, long golden hair drooping over his face.

The audience members are, of course, beside themselves. But the kids are pretty happy, too. It feels much more like a party than a piano recital. There’s none of a recital’s formality, none of its forced silence, and no emphasis on perfection. Outside the building after the performance, a man puts his arm around the shoulder of his 7-year-old son. “Hey that was your first gig!” he says. “That’s pretty cool, dude!” The boy grins bashfully and shrugs.

Gorman shakes hands with everyone as they leave. Then Gorman goes home and locks himself in a room with a microphone for a few hours on end, affecting funny voices and putting the story podcast together.

Rock Band Franchise?

Brian the flower-eating polar bear, in a video made from a Rock Band Land story

“We’re expanding this fall and that’s a good thing,” Gorman says sitting next to Stoesz in the main room at Rock Band Land. His checkered purple shirt matches the lavender walls. “Marcus and I literally are not physically capable of doing any more work than we’re doing right now.”

One big goal in expanding Rock Band Land’s staff is to free Gorman and Stoesz up to build it into an institution worthy of the all the material it generates. “For all the work that we do, and the kids do, it’s a shame that there’s not a broader audience for it. I think that it will fall into place for us,” Gorman says, “eventually.”

His dream is to build Rock Band Land into something with greater reach than the albums, podcasts or stage shows. They’ve already experimented with turning the podcasts into short videos, and with making music videos for some of the songs. Rock Band Land, as an institution, has absolutely no shortage of original material. The plots and characters in the songs and stories often inhabit the same universe, a fictional landscape unique to Rock Band Land.

“If we ever get to the point where we can produce a TV show it’s pretty much already written,” Gorman says. “The only thing we’re short on now is time.”

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list

To learn more about Rock Band Land, check out the website here, or their SoundCloud account.