A Maasai village, (cropped photo by Bill Hertha)

Schizophrenia and schizoid disorders come with a host of symptoms — abnormal sequential thought and trouble with abstract thinking, social isolation, and hallucinations. But at their most-basic level, these diseases are characterized by “abnormal thinking.”

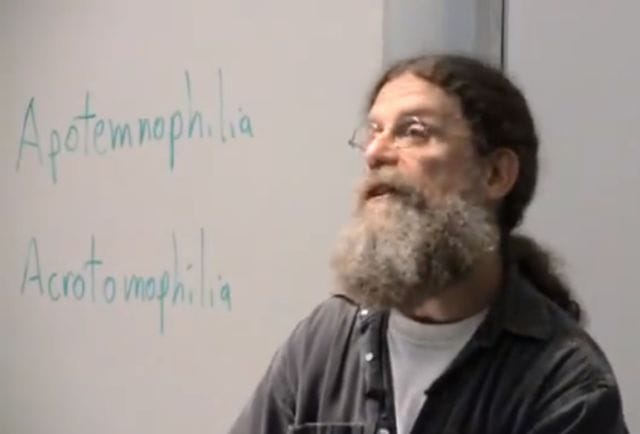

This can make for a kind of sticky diagnosis, when you realize how much the definition of “normal thought” varies from culture to culture. Even the disease’s most obvious symptom — psychotic hallucination — can be hard to pin down. As Robert Sapolsky, the famed neuroscientist and author, has said, “You are on very thin ice deciding you know what counts as abnormal thinking before you have a very wide sense of what can count as normal.”

By way of example, in 2011 he related the following to his students as his only “cross-cultural experience with schizophrenia”:

In the late 1970s and early 1980s he was studying wild baboons in Kenya, near a traditional Masai village. One day a group of his people he knew in the village came “roaring” into his camp, very upset, saying they needed his help in dealing with someone who had done “something very wrong.” The young scientist was eager to help them in any way he could, but also very curious what could possibly be the matter. “These are people who as a puberty rite have to go out and kill a lion or don’t come back,” he explained. “When Maasai are getting all crazed about something, this is something worth paying attention to.”

It turned out they needed his car. On the ride back to the village, they filled him in. They described a woman who had had a schizophrenic psychotic break — at least that’s how it sounded to Sapolsky. “Whoah, this is going to be cool!” he remembers thinking. “This is gonna be really interesting! I wonder what it’ll be like to talk to the family and find out what the symptoms have been! I wonder if she’s going to have any insight!”

What he found was a “huge,” “naked, screaming banshee of a woman,” holding a dead goat in her teeth by the throat, who immediately jumped on top of and tried to strangle him. He was stupefied but, luckily for him, his friends knew what they were doing. They pulled her off of him and wrangled her into the jeep.

One difficult car ride, bruised neck, and an extremely put-upon government clinic later, Sapolsky was driving back to the village with the same party, minus the woman in the throes of psychosis. Not one to be deterred from his anthropological inquiries, he asked his passengers: “So what do you think was wrong with that woman?”

“She’s crazy!” was the obvious, exasperated response.

“How do you know?” he said. “How do you know?”

“She hears voices!”

Sapolsky thought this was a particularly interesting answer from a Masai person. As he was well aware by then, many common Masai rituals include communication with the dead. “Ah, you guys hear voices. What’s the big deal?”

“Idiot!” His friend said. “She hears voices at the wrong times!”

The naked, goat-mangling woman was psychotic, and Sapolsky’s friend was not. And yet they both had sensory experiences of things that according to his understanding of reality could not be real. A clinical term for this is “false perceptions.” The difference was Sapolsky’s friend’s experiences conformed to the Massai understanding of reality. The voices of her ancestors could be real according to her culture’s understanding of reality. What made the crazy woman crazy was that the voices she heard could not.

In 1970, an anthropologist examined 488 societies worldwide. He concluded that in 62% of the cultures studied, “hallucinations played a role in ordinary ritual practices, […] were positively valued, could be understood in the context of local beliefs and practices, and the presence of hallucinations was not usually associated with intake of psychoactive chemicals.”

Because of this, researchers wrote in a cross-disciplinary, ethnographic survey last year, “a clinician should never assume that the mere report of what seems to be a hallucination is a symptom of pathology.” A patient’s cultural background needs to be taken into account. But they also found that the culture’s influence extends past the diagnostic stage: it also affects how people experience pathological psychosis.

People with auditory hallucinations in different cultures tend to hear different voices, delivering different messages. They also tend to develop different attitudes towards their hallucinations. In our culture, people suffering from schizophrenia or other forms of psychosis are more likely than members of other cultures to recognize their hallucinations as a symptom of pathology, but they also tend to have hallucinations that are very violent and negative.

In other cultures, for example, people with schizophrenia are likelier to develop relationships with their voices. Positive relationships. Research suggests that, medically, these people are actually much better off than their Western counterparts, which might mean we should restructure our attitude towards psychosis.

The Voices in Your Head are Culturally Relative

In 2014, Tanya Luhrmann and a research team published a study in which they interviewed three groups of twenty people from three different countries. One group was in San Mateo, California; another was in Chennai, India, and the third was in Accra, a city in Ghana. All sixty participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia, and regularly had auditory hallucinations.

One thing they found was — consistent with prior research — almost all of the American subjects labeled themselves as ‘crazy’. “[A]ll but three spontaneously described themselves as diagnosed with ‘schizophrenia’ or ‘schizoaffective disorder,’” the paper reads, “and every single person used diagnostic categories in conversation.” In contrast, only four of twenty South Asian subjects used the term ‘schizophrenia,’ and only two of the African patients did. From the paper:

“Although many of the Accra participants understood that hearing audible voices could be a sign of a psychiatric illness, their social world accepts that there are human-like non-embodied spirits that can talk. ‘Voices [are] spirits,’ one man explained.”

Another thing they found was that the subjects in India and Ghana were “not as troubled by the presence of voices they could not control.” And this made sense because the Americans’ hallucinations seemed much more aggressive and violent. Fourteen of the American subjects said their voices encouraged them towards violence (to themselves or others). One described, “Usually, it’s like torturing people, to take their eye out with a fork, or cut someone’s head and drink their blood, really nasty stuff.” Only three Indian subjects said their voices encouraged violence, and only two African subjects.

A man and a woman in Accra, (photo by Adam Cohn)

The African subjects tended to hear God’s voice but, much more than the American’s subjects who a voice as “God’s”, they saw God as their protector. In both the African and Indian group, subjects were more likely to have developed relationships with their voices. More than half of the Indian subjects heard the voices of family members, and most of their voices commanded them towards domestic tasks. (This is in stark contrast to the American subjects — only two of them heard “family members”, and those cases were complicated. [B]oth these were women molested by [a family member] who heard their (negative) molester’s voice.”)

Five of the Indian subjects had predominantly positive voice-hearing experiences, and a 10 of the African subjects did (fifty percent of the sample). Some even insisted that they had only positive interactions with the voices. Not one American reported a predominantly positive experience.

Befriending the Disease

Altered photo by George Parilla

The researchers’ hypothesis is that these two phenomena — the tendency for Americans to dislike their voices more, and to find them intrusive; and the American tendency to self-assign diagnostic labels — are related. “We suspect that the American cultural emphasis on individual autonomy,” the paper reads, “shapes […] a general cognitive bias that unusual auditory events are symptoms, rather than people or spirits.”

If your only explanation for an auditory hallucination is that you must be going crazy and you have to fight it, you’re going to develop a very different relationship to your illness — and yourself — than if you believe you could be visited by a ghost or a God.

There’s some hope: culture is plastic. It seems that American hallucinations were not always so violent. The survey mentioned at the beginning of this article cites one longitudinal study from the 1980s. Researchers compared the records of hallucinations reported by patients in a hospital in East Texas in the 1980s to the records from patients in the same hospital in the 1930s (matching for age, race, and gender):

“The hallucinations [that issued a command to the patient] of the 1930s were primarily benign and religious (“live right”, “lean on the Lord”), but those of the 1980s were negative and destructive (“kill yourself”, “kill your mother”).”

The imaginary phenomena of the American mentally ill had gotten much darker in just 50 years. Maybe, in the coming years, culture can shift to ease the burden of people with auditory hallucinations. “[S]chizophrenia has a more benign course and outcome outside the West,” Luhrmann’s paper mentions, also noting, “More benign voices may contribute to more benign course and outcome.”

The researchers do not suggest we promote a belief in ghosts and spirits in contemporary American society, for their psychiatric benefits. But they do mention some therapies — which treat patients to name and respect their voices — that may alter the content of patients’ hallucinations, and thereby ease their suffering.

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list