Winners of Nigeria’s massive business plan competition, YouWin, celebrate their victory.

Youth unemployment in developing countries is one of the world’s great problems. The Economist referred to it as an “epidemic” with possibly disastrous economic and political consequences. Using World Bank data, The Economist estimated in 2013 that almost 25% of 15- to 24-year-olds worldwide are neither working nor in school, and more than 50% are outside the formal economy. The vast majority of these people are from developing countries that are experiencing skyrocketing population growth.

Nigeria, the 7th most populous country in the world and the largest in Africa, is the poster boy for high unemployment combined with high population growth. The Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics reported a youth unemployment rate of over 50%, while the country’s population is growing at 2.8%, easily the highest growth rate among the world’s 20 most populous countries.

Facing this seemingly intractable problem, the Nigerian government had a radical and surprising idea: The largest business plan competition the world has ever seen.

From 2012 to 2015,the government gave away over $100 million dollars to over 3,000 entrepreneurs as part of the YouWin competition. More than $50 million has already been disbursed. The winning entrepreneurs have received grants averaging $50,000 dollars to start or expand a business, and thus create jobs. Only people ages 40 and younger were allowed to apply.

The World Bank recently released an impact evaluation of this program, and the results were remarkable. Where many other attempts to increase employment have failed, YouWin has seen impressive success. Many businesses it funded grew into sizeable and profitable operations, and over 7,000 jobs were created.

After reviewing the results, economist and blogger Chris Blattman asked, “Is this the most effective development program in history?”

A government notice promoting the YouWin program.

Since Nigeria gained its independence from the British in 1960, the country has been beset by political instability and, until about 2000, slow economic growth. Over the last 15 years, the country’s economy has grown rapidly, but at the same time, the unemployment and poverty rate has been on the rise. In Nigeria’s case, rising tides have not lifted all boats. The growing inequality and lack of jobs has been a boon to the recruiting efforts of Boko Haram, a terrorist group fighting an insurgency in the Northeast part of the country.

The Nigerian government has implemented a variety of initiatives targeting youth unemployment. These programs include skills development programs to place people in industry, paid internships to connect college graduates to firms, and an assistance program for young people interested in high yield agriculture.

The effectiveness of existing programs is up for debate, but they have not solved the problem. Over half of the over 30 million Nigerians between the ages of 18 and 35 are still unemployed.

By 2050, Nigeria is projected to be the the 3rd most populous country in the world. Via Economist

Many economists believe that the best ways to create new jobs is to improve conditions for startups. Unlike well-established businesses, successful startups can grow fast and hire extensively. Some researchers have found that almost all of yearly job growth in the United States comes from new firms less than 5-years-old.

Until recently, Nigeria has seen little of this high-growth entrepreneurship. The government wanted to change that. But how do you stimulate entrepreneurialism? Get the needed capital to the ambitious Nigerian who will start the next IROKO, a Nigerian internet platform called the “The African Netflix”?

The Nigerian government found a potential answer, the business plan competition, whose origins lay 7,000 miles away and thirty years in the past.

The YouWin program logo.

In the early 1980s, several MBA students at the University of Texas were jealous of the law students. They wanted access to a fun, competitive activity like the “moot court” competitions available to those at the law school. So they created a business plan competition for MBAs. Student competitors generated business ideas, developed a detailed business plan and presented that plan to possible financiers.

The inaugural competition in 1984 was a grand success. Since then, over 50 American business schools have developed similar business plan competitions. Today, Rice University’s competition awards over a million dollars to winners. Billion dollar companies like Pinterest and Akamai emerged from business plan competitions.

In the last decade, business plan competitions have grown popular as a way to stimulate entrepreneurialism in developing countries. Business plan competitions have been launched across the Middle East, Africa, Central America and South Asia. The World Bank’s support for such programs suggests it believes in their promise.

These competitions have an added appeal in the developing world. While ambitious entrepreneurs in the United States can raise funds through Kickstarter or venture capital, the capital markets in Nigeria do not operate as efficiently. As a result, many Nigerian entrepreneurs have have to borrow at real annual interest rates of about 20%—or go without funding. Business plan competitions can address this gap in the market.

Nigeria went all in on this idea. The government created the largest business plan competition the world had ever seen.

In 2011, the former Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan formally launched the first round of the business competition YouWin. In the first of four rounds, the government granted $58 million to 1,200 entrepreneurs. This article focuses on the results for this first round, because there is limited data available on the following three rounds.

Former Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan congratulates a YouWin grantee.

The program was a partnership between the Nigerian Ministry of Finance, the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and the World Bank. The Ministry of Finance paid for the grants, DFID contributed $2 million for administrative costs and the World Bank funded a large impact evaluation.

Nigeria’s reputation for corruption and disorder led people to doubt the project. Michael Wong, an economist at the World Bank who helped design and administer the program, explained, “When I told people we were doing a business plan competition in Nigeria, they would keel over laughing.”

Nigerian leaders were optimistic. Jonathan believed this program would identify the next, great Nigerian businessperson:

“… Bill Gates’ Microsoft and Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook are eloquent testimonies to the capacity of the youth to dream big and win big in an innovative manner. We have such men and women in this land too: our challenge is to find them early, nurture them and encourage them.”

The government encouraged all Nigerians younger than 40 and interested in creating a new business or expanding their existing one to submit an application. 24,000 applications came in from across the country. 85% of these applications were for new businesses and 15% for existing ones. The vast majority came from men.

The submissions were made anonymous and scored by the Nigerian Enterprise Development Center based on business viability, likelihood of job creation and the passion of the applicant. Existing businesses were preferred, under the assumption that having already set up a business displayed some level of commitment. This process whittled the applications down to 6,000 candidates.

The last step of the process was the development of a more detailed business plan. Applicants had to precisely characterize their business’s product, market and projected finances. As part of developing this final business plan, the remaining 6,000 candidates were required to attend a mandatory 4-day business training session. 1,100 applicants did not show up, and the government received about 4,500 fully completed applications. The Enterprise Development Center and PriceWaterHouseCoopers scored the final business plans.

The 480 plans with the best scores were automatically selected as winners. The next 1,920 best submissions were then put at the mercy of chance. 720 of those 1,920 were randomly selected for this grant.

This random selection was done for two reasons. One, as an assurance against corruption. If done properly, this randomization would not allow for applicants to be chosen based on political or ethnic ties. Second, randomization would allow for a robust evaluation of the program. Researchers would compare the outcomes of the 720 winners against the other 1,200 businesses to see if the program really created jobs and spurred business growth.

Eden Andrew-Jaja started an etiquette refining company with her grant.

So can business plan competitions save the world? No. But they seem like they can help.

In August 2015, the World Bank published an evaluation of the YouWin program by the economist David McKenzie. McKenzie analyzed survey data on the 1,920 firms three years after the program began, and found that the grant had a larger impact than he expected. The selected firms were substantially more likely to launch, survive, make profits, and, most importantly, to generate new jobs.

Of the firms evaluated, approximately 60% were new and 40% already existed. McKenzie analyzed these groups separately.

The main impact of the grant was that it seemed to have helped firms get off the ground and survive. Three years after the competition, 91% of entrepreneurs who launched their business after winning the grant were still in operation compared to only 54% of the losing entrepreneurs. For existing businesses, 96% of the grant-winners survived, while only 76% of the losers continued to operate.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; data McKenzie

On average, the new businesses that received the grant employed 5.2 more workers than those that did not. For existing businesses, the randomly selected winners employed 4.4 more workers. As McKenzie explains, this is partly due to firm survival. But even when he looked exclusively at surviving firms, McKenzie found that the winning firms employed more than two additional workers.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; data McKenzie

It is famously difficult for a business in the developing world to grow to ten employees. In Nigeria, 99.6% of firms have less than ten people. One of the goals of YouWin was to help businesses surpass this number.

The program’s success in this respect was impressive. The new business grant-winners reached 10 employees at a rate 4 times greater than those who did not receive the grant. For existing businesses, it was double.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; data McKenzie

The winning firms also had higher profits and revenues. New firms receiving grants had 32% higher sales and 23% higher profits. The existing firm winners had 63% higher sales and 25% higher profits. McKenzie points out that the 480 winners with scores so high that they were not submitted to randomization had even greater profits and sales.

For Michael Wong, a designer of YouWin, the biggest surprise was the success of the new businesses. “Startups are a fairly risky bunch,” he says. “We assumed the failure rate would be extremely high…. with a few doing extremely well.” When the program was being designed, Wong advised the government to focus on granting prize money to existing firms, which he believed would be less risky investments.

After reviewing the results of the study, Wong believes this preference for existing firms was a mistake. Thus far, the new firms have survived at a rate close to that of existing firms, and they have created even more jobs.

McKenzie estimates that the first round of the program generated over 7,000 jobs. He writes, “The business plan competition seems an effective tool for identifying entrepreneurs with much greater scope for growth than the typical microenterprise.” In the very restrained tone of economic papers, this counts as a rousing endorsement.

He calculates that under the most pessimistic scenario, assuming that all 7,000 jobs disappeared immediately after the survey, the cost per job created would be $8,538. This conservative number already “compares favorably to many job creation policy efforts in developing countries,” McKenzie writes, “which have struggled to find significant effects on employment.” Wage subsidy and vocational training programs, some of the most common employment creation interventions, are estimated to have a cost per job of $11,000 to $80,000.

Television producer Anyanyo Ozioma Grace was one of the !YouWin winners.

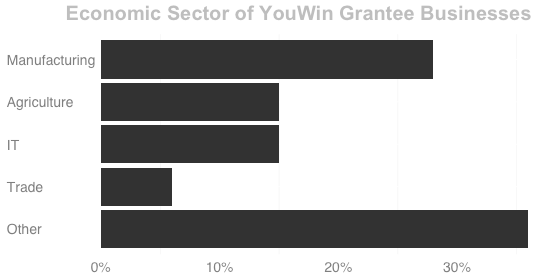

Wong was pleasantly surprised by the variety of the business plans submissions for YouWin. He had figured that almost all of the businesses would be in agriculture and industry, but, in fact, those kinds of businesses only made up half of the winners. He was particularly taken aback by the number of winners in education. A number of private schools won grants, as did a company that made educational comic books.

The YouWin website profiles several winning entrepreneurs. The highlighted winners include Saeed, a young man who is attempting to establish a chain of “one-stop dental centers”, and Alice, a young woman who has expanded her retail and wholesale bakery.

The chart below displays a sector breakdown of the YouWin businesses.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; data McKenzie

Many Nigerians, who were originally skeptical of YouWin, have been won over. Utibe Item, a web developer who received a YouWin grant to expand his company, was amazed that the program was administered so fairly. He told the website AfterSchoolAfrica, “Initially when I saw the advert I didn’t believe it was real. I just said to myself ‘it’s the Nigerian thing. It’s not going to work. One of the ministers will just go to his constituency, pick his family members, and list them as winners’. So I didn’t believe it.” Eventually, Item was sold on the project. He now believes that the project’s intent really is “to empower as many Nigerians as possible” and he has since encouraged others to apply.

There are those that see the program as a failure. When announcing the program, the politicians supporting YouWin suggested it would create 80,000-110,000 jobs. It is unlikely that the program will reach such lofty projections, and pundits have slammed it for not doing so. But this is the fault of political overpromising rather than a blight upon the program.

Other critics see the program as “elitist” because it is oriented towards people with college degrees and the wherewithal to pay for help crafting their business plan. According to Wong, a YouWin consultant industry has popped up across the country.

Since the program’s fourth round began, former President Goodluck Jonathan, a major proponent of YouWin, lost the presidency to Muhammadu Buhari. It is not yet clear how this political transition impacts the future of YouWin, the elimination of the program is under consideration. Michael Wong is optimistic that the new government will see the benefit of the scheme, and that it will continue. He recognizes that business plan competitions are only a “small tool” in the economic development toolbox, but he believes the program has demonstrated a excellent return on investment.

***

Over the last decade, economists found that giving cash to the poor, sometimes conditional on their children going to school or seeing a doctor, is a surprisingly efficient way to help people out of poverty. Some of the more famous examples include Mexico’s Oportunidades and GiveDirectly, which works in Kenya and Uganda. Contrary to the expectations of critics, the recipients rarely squander this money on drugs or gambling. They generally invest it in their family’s most basic needs.

The YouWin program may be seen as a logical extension of these cash transfer programs. The work of GiveDirectly and Oportunidades suggests that recipients of aid often know best how to use it effectively. YouWin’s early success has a similar message. If we want to support entrepreneurs in developing countries, maybe we should just give them the money.

Our next post is about the economics of developing a new, male contraceptive technology. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Dan Kopf; follow him on Twitter here.