Cotton candy, in all of its colorful, puffy glory, is one of those timeless treats capable of evoking childhood with one disintegrating bite.

In fluffy pink bushels, it pervades fairgrounds and festivals. Held high above cheering crowds, it bobbles its way between rows at sporting events. In the presence of snarling circus lions, its airy, delicate fibers are stuffed, soothingly, into the mouths of terrified toddlers. Even in New York’s Four Seasons Restaurant, where dishes soar above $80, the confection is served to patrons post-meal, at no charge. “This restaurant is a cathedral of food,” says the eatery’s maître d. “People come here and they’re not too comfortable. Giving them cotton candy gives them their childhood back.”

Cotton candy is also particularly odd: it’s made up mostly of air and sugar, and contains only trace amounts of flavoring and food coloring. The standard serving, which is larger than the typical child’s head, weighs less than one ounce. Odder yet, the modern invention of cotton candy and its machines stems from a lineage of dentists.

***

Cotton candy’s earliest origins date back to 15th century Italy. Here, in specialty bakeries off cobblestoned streets, sugar syrup would be boiled in a pan and “flicked out” with forks to create decorative, wispy strands. Due to the laborious process and the high price of its only ingredient, this “spun sugar” was only produced in small quantities, exclusively for the uber-wealthy.

For 300 years, the confection stayed in fashion — but only among elite circles. Ornately-spun Easter eggs and “webs of gold and silver” were rare delicacies for high-society Europeans. Italians were particularly skilled at sugar spinning; as one historian describes, Venetians “moulded it into a fantastic tableaux of animals, mythic figures, buildings, birds, and pastoral scenes.” When Henri III of France visited Venice in the late 1500s, he was treated to a fanciful banquet at which 1,286 items — including the tablecloth — were spun of sugar. For the average citizen though, the treat remained widely inaccessible.

Centuries later, in 1897, a 37-year-old dentist from Tennessee decided the sugary goods should be enjoyed by everyone.

Born in Nashville in 1860, James Morrison’s passions were strangely conflicting. He excelled in dentistry school (by 1894, he was named President of the Tennessee State Dental Association), but was also a confection enthusiast with a penchant for culinary advancement. By the mid-1890s, he patented several devices — one which extracted oils from cottonseed and converted them to lard, and another which chemically purified Nashville’s drinking water.

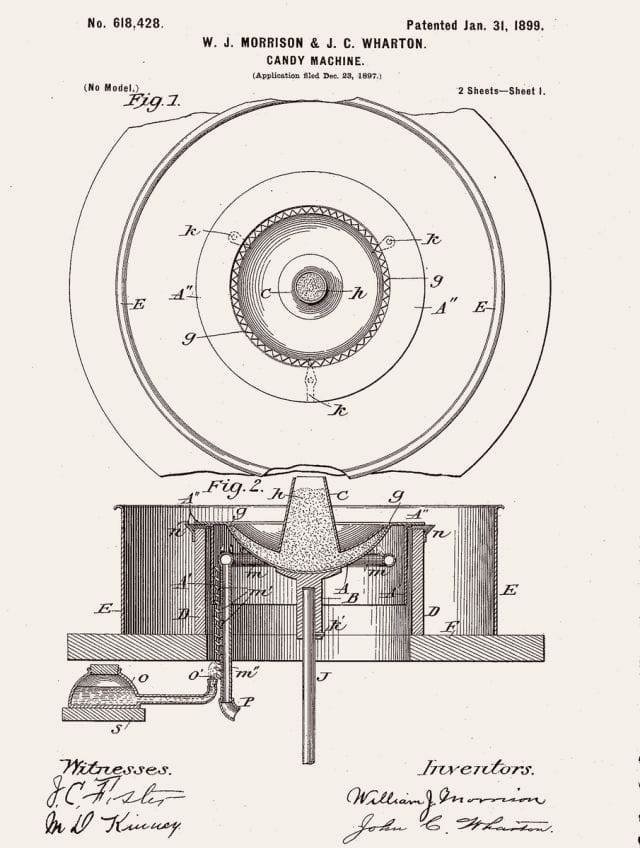

But Morrison’s biggest breakthrough came in 1897, when he paired with John C. Wharton, an old pal and fellow confectioner. Together, the two designed and co-patented what they called the “electric candy machine.” Utilizing centrifugal force, the device rapidly spun and melted sugar through through small holes until it was fluffy and nearly 70% air. They called the new treat “fairy floss,” formed the “Electric Candy Company,” and spent several years perfecting the process before debuting it to the public.

Morrison’s original patent (1899)

At the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition (more popularly known as the 1904 World’s Fair), the duo introduced their product, selling it in small wooden boxes for twenty-five cents each (about $6 today) — nearly half the admission price to the fair. Despite its high price, the candy floss was a smash success. Over 184 days, Morrison and Wharton sold 68,655 boxes, grossing $17,163.75 ($438,344 in 2014 dollars).

The World Fair, which housed 35,000 hungry attendees and had previously been the birthplace of hot dogs, peanut butter, ice cream cones and other legendary treats, honored fairy floss’s success by holding a special “confectioner’s day.”

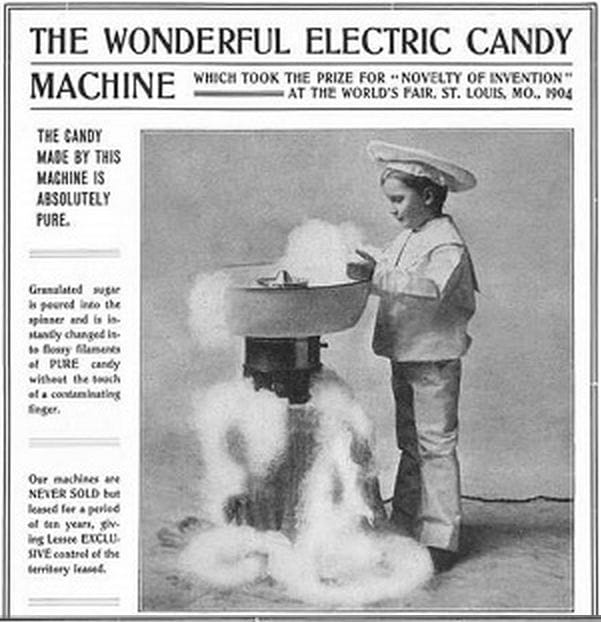

Following the fair, a 1905 advertisement in The New York Times touted the new “Wonderful Candy Machine” as a major breakthrough, with a new reduced price:

“Perhaps you have seen the mysterious vaudeville man eat handfuls of cotton on the stage. You can do the same thing with the candy floss that this new Candy Spinning Machine turns out. It is good to eat and lasts a long time, and doesn’t cost much money — 5 to 10 cents.”

An early advertisement for the Electric Candy Machine

While the dentist’s invention thrived, it proved to be unreliable over time. As the first of its kind, it was plagued by its rudimentary nature: it rattled, randomly shut off, overheated, and was difficult to scale and reproduce. In 1921, shortly after Morrison’s 17-year patent expired, another enterprising dentist, Josef Lascaux, took it upon himself to “reinvent” the machine, but he never followed through with his patent and his advancements didn’t quite pan out. He did, however, coin the term “cotton candy,” and sell it to children at his practice. Over time, this new name replaced the old one (though cotton candy is still called “fairy floss” in Australia).

It wasn’t until 1949, with the introduction of spring-loaded bases, that the cotton candy machine received its first substantial upgrade — so substantial that the company responsible for the innovation, Gold Medal Products (Cincinnati, Ohio), constructs and sells nearly all cotton candy machines in production today. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, a variety of advancements automated the entire process — from spinning to packaging — and expedited the process of creation.

***

Today’s machines are compact, efficient, and fast: they hold up to three pounds of sugar at a time, spin at rates of up to 3,450 revolutions per minute (RPM), and can produce four servings per minute. Industrial wares run anywhere from $500 to $2,000 — not a bad investment, considering the claims one pitch makes: “In as little as two square feet of floor or counter space, you can place this easy-to use cash generator that will continually bring in AT LEAST 90 cents profit on every dollar sold!” As the ingredients of cotton candy are sparse — air, small amounts of sugar, flavoring and dye — each serving yields nearly 100% profit.

If you’re a dentist looking to follow in the footsteps of cotton candy entrepreneurs, there’s another upside to consider: an increase in cavities.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.