It’s 2 AM. You’ve just returned to your hotel room after a night carousing on the town. The corner stores have long-since closed, and you’ve been left tipsy, alone, and in need of an after-hours morsel. And then, like some culinary apparition, it beckons you from the corner of the room: the hotel mini-bar.

At some point, despite our better judgement (or thanks to a generous expense account), we’ve all ceded to the temptation of this invention’s price-bloated contents — whether in the form of $13 cashews or a $6 water bottle. Sometimes it’s for lack of alternate options, and sometimes, it’s just because we’re lazy; the mini-bar caters to these situations without discrimination.

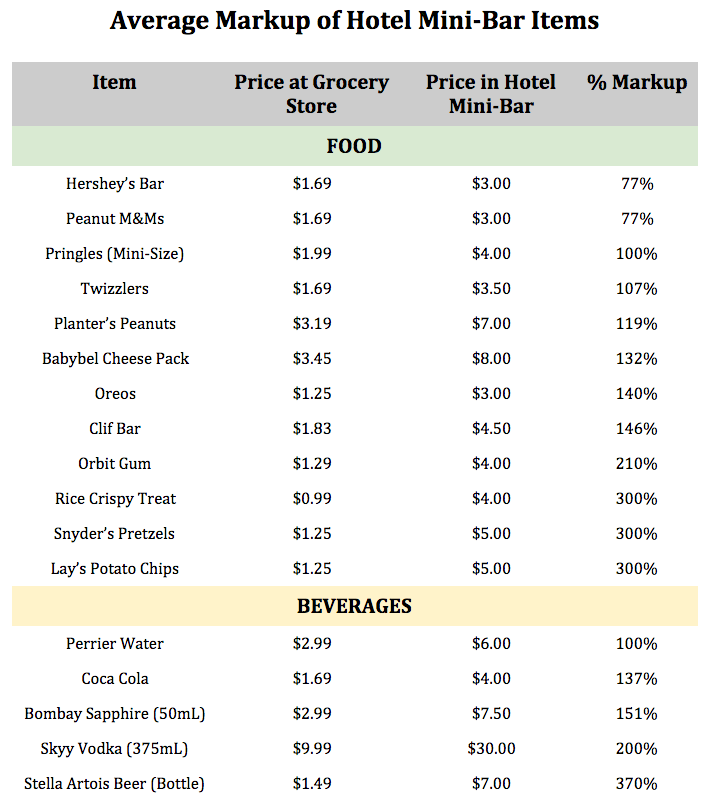

Here’s a price sampling that might look familiar to you:

Data via Mint.com

At some hotels, $7 peanuts are considered paltry: gummy bears are jacked up as much as 1,300% at New York’s upscale Omni Berkshire Place, while a bottle of “premium” water runs $25 at Trump International Hotel & Tower in Chicago.

But despite these figures, most hotel managers claim that their fridges operate at a loss, and are nothing more than an outdated perk to guests. Is the hotel mini-bar on its way out?

Birth of the Mini-Bar

When German-run company Siegas invented the mini-bar in the early 1960s, it was an instant hit with luxury hoteliers. First integrated in the suites of Washington D.C.’s Madison Hotel in 1963, mini-bars became an expected perk at high-end chains — and despite high mark ups, guests indulged in the snacks and beverages inside of them.

In 1974, the Hong Kong Hilton became the first hotel to include a “liquor-stocked” mini-bar in each of its 840 rooms, and it proved to be lucrative: in-room drink sales skyrocketed 500%, and the company’s overall revenue was boosted by 5%. Riding on the coattails of this success, Hilton’s executive team integrated mini-bars into all of their locations worldwide.

By the end of the decade, most 4 and 5 star hotel rooms housed a mini-bar, and the device was at the height of its renaissance.

But hotels would soon learn that the minibar came with a number of problems: it required additional labor (usually, in the form of a dedicated “mini-bar operator”), the overstocking of goods routinely led to “spoilage,” and guests stole items — specifically the tiny bottles of vodka, which were often consumed and refilled with water.

Over time, managers have come to realize that the mini-bar is far from an idyllic cash cow. In a 2012 survey, nearly 500 hotel owners unanimously agreed that re-stocking mini-bars was a “nightmare,” and 84% reported they’d had guests dodge bills by stealing items and replacing them with inferior goods.

Goodbye, Sweet $9 Toblerone Bar

In today’s hotel economy, the once-briefly-popular mini-bar is now what one industry analyst calls “a relic of the past”. In a 2013 consumer study that surveyed some 20,000 travelers, it was ranked as the “least important” amenity in a hotel room, with only 21% of respondents desiring one. Marginalized by in-room Wi-Fi and continental breakfast, the mini-bar is a shadow of what it once was.

According to a report by PKF Hospitality Research, which analyzed data from 667 full-service hotels, mini-bar sales have dropped 28% from 2007 to 2012:

Data via PKF Hospitality Research’s “Annual Trends in the Hotel Industry” report

It comes as no surprise then, that many hotels are opting to phase them out. In 2004, New York’s Marriott Marquis — a 4-star behemoth in Times Square — excavated all 1,946 of its mini-bars, citing unfavorable operation costs and dwindling popularity. Most Hyatt and Hilton locations (which once housed the world’s first mini-bars) have followed suit. One New York City hotel manager elaborated on her reasoning in an interview with Food Arts:

“We had eight full-time mini-bar staffers who each checked 150 rooms a day [and] they simply couldn’t get to every room every day. Plus, we found that guests weren’t using the mini-bars as much as one would think. In Times Square, many retail outlets are open 24/7, so beverages and snacks are available everywhere, all the time. In addition, some mini-bar items have expiration dates, and we were throwing items away. It was a pure business decision: mini-bars were not profitable.”

This shift, writes The Economist, could also be due to the changing culture of travel:

“Expense accounts are more closely monitored these days; drinking on the company’s dime is generally less acceptable than it was. Travel in general has become more commoditized and more widely accessible, and budget travelers are unlikely to spend $15 on one drink. Many higher-end hotels now have shops inside, most have bars where hotel guests can go for a drink instead of moping around in their room with a miniature bottle of scotch.”

Increasingly, hotels are opting to leave empty fridges in rooms, and allowing guests to stock them at their own leisure.

Don’t Even Think About Touching That

Despite this general annihilation of mini-bars, some hotels have elected to keep them — and in order to viably do so, they’ve turned to technology.

Some 85% of the remaining hotel mini-bars now come equipped with built-in electronic sensors and scales to detect when items have been removed or tampered with. Other companies, like eRoomSystem Technologies, offer hotels state-of-the-art beverage safes that automatically charge guests using a system of infrared sensors. The mini-bar, writes The Atlantic, has morphed into “a supermax prison for sodas and candy.”

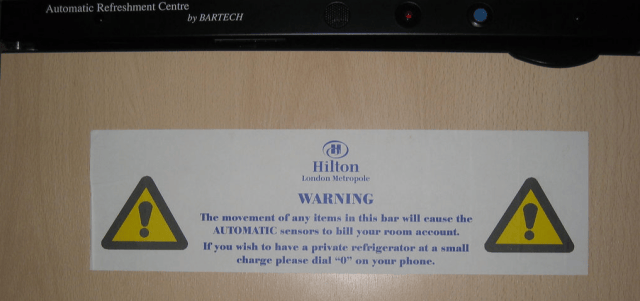

A mini-bar warns of what will happen if you tamper with its sensors; via Nic Walker

In this newfangled system, a sensor is placed beneath each snack, and if any change in presence is detected, the item’s value is tacked on as “incidental” fees on the bill. Often, the highly sensitive nature of these rigs results in faulty charges.

One journalist staying at a DoubleTree hotel in Chicago reported incurring six such charges, ranging from $6.06 to $7.72, for merely picking up treats from the mini-bar. Many hotels also now openly display snacks on scale-equipped trays, imploring the guest to give them a once-over. At the Wynn in Las Vegas, snack-stuffed trays are perched atop the mini-bar, and when an item is fondled by a curious guest, its value is automatically added to the bill, even if it isn’t consumed.

“Nine times out of 10, it just means something was picked up and put back,” a hotel insider told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in an interview. “No computer is a foolproof system. You always need human interaction.”

More often than not, it is the guest’s responsibility to check over her bill and ensure that she hasn’t been inappropriately charged. Jacob Tomsky, who worked at a major hotel chain for more than a decade, writes that, as a front desk clerk, mini-bar charges were “without question, the most disputed charges” on any bill:

“The process for applying these charges is horribly inexact. Keystroke errors, delays in restocking, double stocking, and hundreds of other missteps make mini-bar charges the most voided item. Even before guests can manage to get through half of the ‘I never had those items’ sentence, I have already removed the charges and am now simply waiting for them to wrap up the overly zealous denial so we can both move on with our lives.”

Still, these efforts have not curbed the costs for hotels that continue to equip rooms with mini-bars. It seems dubious that anything — whether it be a $13 bag of nuts, or a system of sensors — can stop the fate of the mini-bar. And most hotel frequenters couldn’t care less.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.