EDITOR’S NOTE:

Last Wednesday (January 28th, 2015), at approximately 6:45pm, a fire broke out in a commercial-residential building at Mission and 22nd Streets in San Francisco. In the aftermath, one man is dead, three are injured, and some 64 individuals (including 16 children), are left without a home. The vast majority of these residents are low-income, Latino families who had been living in the 108-year-old building for decades. They have lost everything — valuables, documents, cash savings, quinciñera dresses, family heirlooms.

This feature is the first of a series of these families’ stories we’ll be telling over the next few days. Our hope is to put faces behind this tragedy, and to raise money for a fire relief fund started by the author, who is a writer for this blog.

![]()

It’s 6:40 PM, and Toni Segovia has just wrapped up a long, back-breaking work day that began at dawn. The 42-year-old construction worker removes his vest, and unfastens his toolbelt. He’s thirsty, exhausted, ready to sit and relax with his children at home.

Shortly after picking up his wife, Nancy, Toni’s phone buzzes: it’s his 13-year-old son, “Tonito.” The father expects his son has a question about dinner, or where to find the television remote. Instead, he’s greeted with stammering, sobbing, sirens; over the din of unfamiliar voices, Toni can only pick out bits and pieces of what is said: “Building….Fire…Burning…”

Toni floors his vehicle and races down Valencia Street. At some point — he can’t remember when — he leaves the car with his wife, Nancy, and takes off sprinting toward 22nd Street and Mission. He sees the smoke rising in a black plume above the streets; as he nears his home, he breaks through the crowds that have amassed, and scans faces.

Finally, his eyes fall on his children, Tonito and Perla; in a sea of spectators’ cell phone screens, they embrace and cry. Together, in the shadows across the street, the Segovia-Caro family turns and watches the only place they’ve ever called home erupt in flames.

***

For Toni Segovia, apartment #308 on 3222 Mission Street was more than a place to live: it was the lens through which he experienced what he calls the “best times I’ve had.”

In 1989, at 14 years old, he fled civil war-torn El Salvador with his parents, older sister, and relatives, and settled in San Francisco’s largely Latino Mission District. At the time, the neighborhood was experiencing an influx in Central and South American immigrants seeking refuge from hostile political climates; Toni and his family found themselves at home in the community.

After a few years of bouncing around between different studios in the building, Toni’s family secured apartment #308, one of the biggest two-bedrooms in the complex. “At that time it was easy,” he reminisces. “The management didn’t ask for credit or background. They just told us the place was available, and we moved.”

The cream-colored corner unit overlooking Mission Street would be where Toni would spend the next 25 years of his life.

After graduating high school in the city, he says he “didn’t have the opportunity to [go to college];” instead, he found work as a busboy at a hotel restaurant. Over the next few years, he held various odd jobs — “anything I could get,” — to help support his parents. It was through this varied employment that he eventually made a connection in the construction industry; soon, he’d accrued a stable career in the field. All the while, Toni remained in unit #308.

Toni’s unit was one of roughly 20 that occupied the third floor of 3222 Mission Street; the majority of the building’s first and second floors were occupied by businesses all of sorts — a flower shop, a travel agency, a local paper, markets, and eateries. It was in one of these establishments — Taqueria La Altena — where Toni met his future wife.

“I met Nancy down in La Altena, below the building, in 2000,” he says. “She used to work there at the front. I ate there so I could go see her.”

The two fell in love and married.

Shortly thereafter, Nancy brought her first child, Perla, then three years old, over from Mexico; a year later, in 2001, Tonito was born. After Toni helped his parents retire to a much-cheaper Central California home, he settled into unit #308 with his new family, and they made it their own.

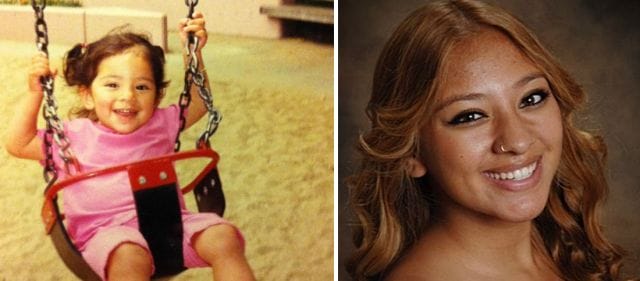

Toni, with his Daughter, Perla, a few months before the fire

Perla, now a 17-year-old high school senior, was just returning home to change for a church service, when the fire broke out.

“I had been hanging out with my boyfriend,” she says, “and I went up the stairs to my [apartment] as if it were a regular Wednesday night. As I was opening my door, I saw my neighbor run out of his apartment, yelling, ‘Call 911! Call 911!’ In my head, I was like, ‘What’s going on?’ Then I saw smoke coming out of my apartment.”

She ran inside the apartment to see her younger brother, Tonito, standing in the middle of the room, “all dressed up” in his church clothes; the room was smoky and hot, and she could tell that the source of the fire wasn’t far from where they stood. Somehow, she says, she had the clarity to call 911, usher both her brother and the family dog out of the room, and redirect a crowd of confused tenants out of the building.

“There were a bunch of people in the elevator, waiting,” she recalls. “I was yelling at everyone to get out of the elevator and go down the stairs…right after we got out of the building, my neighbor’s window blew up.”

As far back as she can remember, Perla called apartment #308 home. It was here where she celebrated her third birthday party with close friends and neighbors, some of whom still lived in the building. One of these friends, Mayra Alvarez, also now a 17-year-old high school senior, grew up in apartment #316 just down the hall. Ever since, the two have been inseparable — “like sisters.”

“We’ve known each other since we were two,” says Mayra, nodding to a smiling Perla, who’s perched by her side. “We went to the same elementary school, go to the same high school now, and–”

“And, we’ve been best friends ever since!” interrupts Perla. They both laugh.

***

Mayra’s recollection of the fire is vivid, and especially terrifying.

As she and her mother sat down to eat dinner (Mayra’s older brother and her mother’s partner were away), they began to hear an increasing number of sirens. It was nothing out of the usual in the heart of a city, but Mayra’s mother had a bad feeling, and as was the case, mothers’ bad feelings usually hold merit.

“When my mom opened the front door, it was pitch black in the hallway, as dark as that screen,” says Mayra, pointing to a television on a wall of the family friend’s apartment they’re temporarily staying in. Mayra, along with other residents, would later relate to me that the building was potentially not up-to-code with fire regulations: many of the building’s smoke alarms failed to go off, a few of the extinguishers didn’t expel retardant, and the fire escape door on her floor was chained shut.

While Mayra’s mother was “freaking out,” she says she tried to remain calm and find an escape route. A series of nightmarish failures ensued:

“My first reaction was [to try] the fire escape. I ran to my mom’s room, but the window wouldn’t open. When I looked outside, I remembered the windows had bars on them; either way, I thought, ‘Why try? We’re not going to be able to get out.’ I thought to go through the kitchen window instead, and started thinking about throwing stuff out that we could save. I’m pretty athletic, and I knew I could climb down, but then my mom wouldn’t be able to.”

In the chaos, Mayra’s mother yelled out for help — luckily, just at the moment that San Francisco firefighters were entering the building. They quickly escorted Marya and her mother through the hallway, where Mayra, who has asthma, struggled to breathe. On the way to safety, she tripped over something. “I didn’t know what it was,” she says. “I found out later, it was a lady on the ground..”

The woman Marya stumbled over was ultimately uninjured, but others were not so lucky: one man perished, and three were taken by ambulance to hospitals and treated for third-degree burns.

Mayra at 4; Mayra at 17

Marya only managed to grab a few relics of her previous life: her cell phone, her backpack, and a purse. Everything else was lost, including cash that she’d been saving since she was 12 years old — cash she’d earned by babysitting for “rich” people. “They work at Google, Facebook…one invents iPad games,” she says with a fluttering voice “They come from wealthy families.”

She has also lost treasures that can never be replaced: the elaborate dress she wore on her quinceañera (a girl’s fifteenth birthday celebration, and an important coming of age ceremony in Latino culture), the blanket she was wrapped in as an infant, her grandmother’s last piece of jewelry.

Things like this are gone, but the fire can’t take away Mayra’s memories of growing up in the Mission. And luckily, she has plenty.

“My mom always used to say, she’d rather live in a small place and stay in the Mission than get a house and leave the city,” says Mayra. “We love it here.”

She remembers the third floor of the building — which housed the residents — as one big family. Neighbors had no qualms about leaving their doors unlocked, or sharing meals:

“The girl who lived across from us was really young. Sometimes, I would get out of the bathroom, and she’d be sitting on our couch…It was a building where we were able to keep our doors open, and there were no safety concerns. We would just trust nothing bad would ever happen.”

“Me and Perla would walk by each other’s doors, and our moms would say ‘Want dinner? Wanna eat?’” she adds. “That’s the kind of place it was.”

***

Like everyone else in the building, Mayra and Perla have had to cope with losing just about everything. But the local community has made sure to restore anything they can.

Mayra, who, in addition to being an honor role student, is the captain of Galileo High School’s soccer team, lost her cleats and all her gear in the fire. “I thought, ‘Well, I can’t play this year,” says Mayra, “but, then my coach bought me brand new cleats, warm-up gear — everything.” Mayra’s 21-year-old brother, who she calls “a game freak,” lost his console and games; his fellow employees at GameStop are banding together to buy him a new Xbox One.

Perla, who calls herself “more of a girly-girl than Mayra,” competes in beauty pageants, and recently landed a job as an administrative assistant for Miss Asian Global America (“I’m the only Latina there,” she laughs). Next month, she plans to compete in a large pageant, despite losing her heels, dresses, and jewelry. “The past queens, present queens, and founder of pageant have been really supportive,” she says.

Perla, preparing for her senior portrait

Both girls lost their computers, textbooks, and school work, and Galileo High has been understanding and supportive — though, as studious pupils, they’re still concerned. School policy says that if you don’t return your textbooks, you can’t graduate,” Perla jokes. “All our textbooks got burned, so I’m hoping they make an exception.”

More taxing is the emotional toil the experience has had on the girls. While their classmates bask in the glory of senior year and celebrate their accomplishments, Perla and Maya feel a heavy sense of responsibility.

The girls, who had just applied to college less than a month prior to the fire, each have a distinctive dream. Mayra, who has “always been interested in helping people,” wishes to attend the nursing program at Dominican University in San Rafael, about 30 minutes north of San Francisco. Perla would like to attend Syracuse University in New York and work toward becoming an early childhood education teacher — though, the disaster has impacted her desire to leave home, and her family.

“Now that everything happened, I don’t want to go as far away,” says Perla, softly. “I can’t leave everything the way is it, now that this happened. It would make it more difficult to move on.”

“I’ve worked so hard to have a better future,” adds Mayra, “and now I feel, like, guilty for leaving to college.”

***

Every few moments during our interview, Toni turns away from me to look out of the window. In the glow of the mid-day sun, I can see a crease form between his eyes. He’s in an armchair at a friend’s apartment in the Mission; across from him, Perla and her friend, Mayra, sit on the couch. We listen to the clock tick.

Speaking slowly, Toni takes me through the days following the fire — the emergency meetings, an assessment with the Red Cross, and finally, his family’s brief stay at the Salvation Army shelter, where most of the affected residents were placed.

“The first three nights,” he admits, “I couldn’t sleep.” Nearly a week later, he still hasn’t sat down and eaten a full meal; when he tries to, his stomach twists up. “We made jokes at the shelter at night, but when I look in their faces — my son, my daughter — I can see their trouble.”

The best Toni could do was sit and watch Tonito, play with the other children in the building, enjoying his son’s fleeting moments of joy. “Sometimes, I see he’s happy,” says Toni. “At the same time, when he has nobody to play with, I can see in his face that he is hurting. He is sad.”

While the city reaches out to low-income housing programs and struggles relocate the families, officials have begun the process of shifting some of the responsibility onto the parents. “They told us, ‘Start looking on your own,’’” says Toni. For now, his friend’s place will do — but only until Thursday. After that, Toni will either ask another friend for help, or return to the shelter.

When incidents like this happen, tenants are legally entitled to return to their units, once the units have been repaired, at their former rent prices. There are, however, many loopholes to this. If a tenant accepts his security deposit back or takes any other financial offer from the building owner, for instance, he could lose this right. What’s more, if 75% of the building is deemed “a new development” upon restoration, this right is terminated, essentially punishing the tenants for the severity of the fire. With damages on Toni’s building estimated at over $8 million, this is a likely scenario.

Staying in the Mission — the only place Toni, Perla, and Mayra have ever called home in America — is a major concern.

“Our rent didn’t raise too much — only, like $60 every two years,” says Toni. “Our unit was the biggest one in the building, and we paid less than $1,100 [per month].” Finding something comparable in San Francisco’s increasingly-heated and crowded real estate market will be a daunting task.

Yet through all of this, Toni continues to work his construction job — he “has to,” he says, “to support the family.” A half-hour later, he excuses himself to do just that.

Just before leaving, the robust, proud man pauses and turns.

“The Mission is my home, you know…” He’s struggling to find the right words, but it’s clear they’re coming from a deep place. “It’s my home.”

________________________________________________________________

Last week, after witnessing the fire while biking home, I set up a GoFundMe page for the families affected by this fire, with the goal of raising $2,000. So far, the community has come together to raise $108,000. I’m currently working with MEDA, a local non-profit, to make sure these funds are distributed to ALL affected families in cash payments by the end of this month. If you’d like to help Toni’s family, and others, get back on their feet while they await relocation, please consider donating. Anything helps.

In addition to my fund, Perla (Toni’s daughter), and Mayra, have each launched their own independent campaigns. They can be found here (Perla), and here (Mayra).

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.