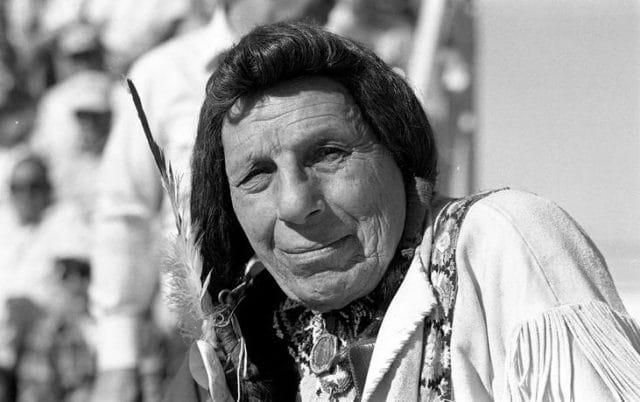

On Earth Day, 1971, nonprofit organization Keep America Beautiful launched what the Ad Council would later call one of the “50 greatest commercials of all time.” Dubbed “The Crying Indian,” the one-minute PSA features a Native American man paddling down a junk-infested river, surrounded by smog, pollution, and trash; as he hauls his canoe onto the plastic-infested shore, a bag of rubbish is tossed from a car window, exploding at his feet. The camera then pans to the Indian’s cheerless face just as a single tear rolls down his cheek.

The ad, which sought to combat pollution, was widely successful: It secured two Clio awards, incited a frenzy of community involvement, and helped reduce litter by 88% across 38 states. Its star performer, a man who went by the name “Iron Eyes Cody,” subsequently became the “face of Native Indians,” and was honored with a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame. Advertisers estimate that his face, plastered on billboards, posters, and magazine ads, has been viewed 14 billion times, easily making him the most recognizable Native American figure of the century.

But while Hollywood trumpeted Iron Eyes Cody as a “true Native American” and profited from his ubiquitous image, the man himself harbored an unspoken secret: he was 100% Italian.

America’s Favorite Indian

Long before his fame in the 1970s, Iron Eyes Cody had carved out a niche for himself in Hollywood’s Western film community as “the noble Indian.” With his striking, “indigenous” looks, he perfectly fit the bill for what producers were looking for — and his story correlated. Until the late 1990s, Iron Eyes’ personal history (provided solely by himself) was that he’d descended from a Cherokee father and a Cree mother, and had been born under the name “Little Eagle.” An old archived article filed in the Glendale Special Collections library elaborates on his account:

“Iron Eyes learned much of his Indian lore in the days when, as a youth, he toured the country with his father, Thomas Long Plume, in a wild west show. During his travels, he taught himself the sign language of other tribes of Indians.”

From 1930 to the late 1980s, Iron Eyes starred in a variety of Western films alongside the likes of John Wayne, Steve McQueen, and Ronald Reagan. Clad in headdresses and traditional garb, he portrayed Crazy Horse in Sitting Bull (1954), galloped through the plains in The Great Sioux Massacre (1965), and appeared in over 100 television programs. When major motion picture houses needed to verify the authenticity of tribal dances and attire, Iron Eyes was brought in as a consultant. He even provided the “ancestral chanting” on Joni Mitchell’s 1988 album, Chalk Mark in a Rainstorm.

By all accounts, he was Hollywood’s — and America’s — favorite Native American.

But several (real) Native American actors soon came to doubt Iron Eyes’ authenticity. Jay Silverheels, the Indian actor who played “Tonto” in The Lone Ranger, pointed out inaccuracies in Iron Eyes’ story; Running Deer, a Native American stuntman, agreed that there was something strangely off-putting about the man’s heritage. It wasn’t until years later that these doubts were affirmed.

The Italian Cherokee

In 1996, a journalist with The New Orleans Times-Picayune ventured to Gueydan, Louisiana, the small town Iron Eyes had allegedly grown up in, and sought out his heritage. Here, it was revealed that “America’s favorite Indian” was actually a second-generation Italian.

“He just left,” recalled his sister, Mae Abshire Duhon, “and the next thing we heard was that he had turned Indian.”

At first, residents of Gueydan were reticent to reveal Iron Eyes’ true story — simply because they were proud he’d hailed from there, and didn’t want his image tarnished. Hollywood, along with the ad agencies that had profited from his image, was wary to accept the man’s tale as fabricated. The story didn’t hit the newswires and was slow to gain steam, but The Crying Indian’s cover was eventually blown.

Iron Eyes Cody, or “Espera Oscar de Corti,” was born in a rural southwestern Louisiana town on April 3, 1904, the second of four children. His parents, Antonio de Corti and Francesca Salpietra had both emigrated from Sicily, Italy just a few years prior.

Five years later, Antonio abandoned the family and left for Texas, taking with him Oscar and his two brothers. It was here, in the windswept deserts, that Oscar was exposed to Western films, and developed an affinity for Native American culture. In 1919, film producers visited the area to shoot a silent film, “Back to God’s Country;” Oscar was cast as a Native American child. The experience impacted him greatly, and, following his father’s death in 1924, he migrated to California to forge a career as an actor.

Once in Hollywood, he’d changed his name to “Cody” and, to attract the attention of producers looking for authenticity, had begun acting under the moniker “Iron Eyes.”

Legacy

Even after his history was revealed, Iron Eyes Cody refused to admit the truth behind it. He continued to wear his braided wig, headdress, and moccasins, and was unrelenting in supporting the Native American community.

He toured on a lecture circuit, reminding Indians of their traditions, and admonishing them against gambling and the use of alcohol. “Nearly all my life, it has been my policy to help those less fortunate than myself,” he later told the press. “My foremost endeavors have been with the help of the Great Spirit to dignify my People’s image through humility and love of my country. If I have done that, then I have done all I need to do.”

Iron Eyes Cody peacefully passed away in 1999, at the age of 94, leaving behind a poetic homage to the culture he believed in. “Make me ready to stand before you with clean and straight eyes,” he wrote. “When Life fades, as the fading sunset, may our spirits stand before you without shame.”

If you liked this blog post, you’ll be mildly amused by our book → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.