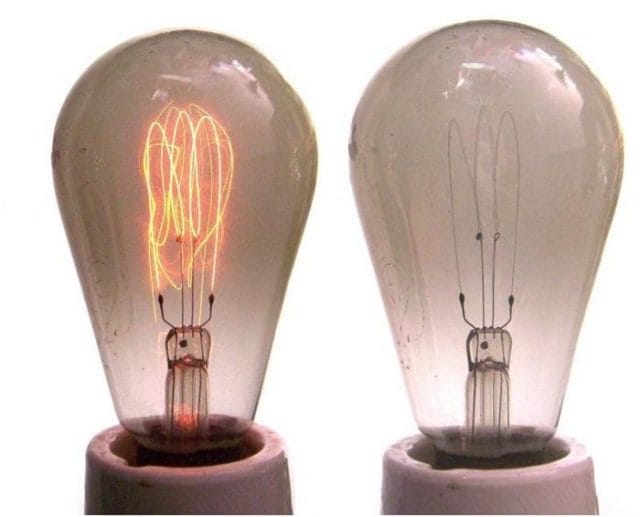

In the United States, the average incandescent light bulb (that is, a bulb heated with a wire filament) has a lifespan of about 1,000 to 2,000 hours. Light emitting diode (LED) bulbs, which are increasingly replacing incandescent bulbs, are said to last between 25,000 and 50,000 hours — an incredible bump.

But dangling from the ceiling of a California firehouse is a bulb that’s burned for 989,000 hours — nearly 113 years. Since its first installation in 1901, it has rarely been turned off, has outlived every firefighter from the era, and has been proclaimed the “Eternal Light” by General Electric experts and physicists around the world.

Tracing the origins of the bulb — known as the Centennial Light — raises questions as to whether it is a miracle of physics, or a sign that new bulbs are weaker. Its longevity still remains a mystery.

A Brief History of the Light Bulb

While it is generally reported that Thomas Edison “invented” the light bulb in 1879, a long lineage of innovators preceded him.

In 1802, British chemist Humphry Davy produced incandescent light by passing current through thin strips of platinum; over the next 75 years, his experiments would be the basis of many efforts to produce long-lasting, bright light through heated filaments. Scottish inventor James Bowman Lindsay boasted, in 1835, of his new light that allowed him to “read a book at a distance of one and half feet,” but soon after abandoned his efforts to focus on wireless telegraphy. Five years later, a team of British scientists toyed with heating platinum filaments inside a vacuum tube. Though the high price of platinum made the device inaccessible and difficult to scale, this design formed the basis for the first incandescent lamp patent in 1841.

With his integration of carbon filaments in 1845, American inventor John W. Starr arguably could have been credited as the light bulb’s inventor, but he died of tuberculosis the following year, and his colleagues were unable to pursue the idea without his knowledge and expertise. A few years later, British physicist Joseph Swan utilized Starr’s advancements to produce a working bulb, and, in 1878, became the first man in the world to brighten his home with bulbs.

Meanwhile, in America, Thomas Edison worked on improving carbon filaments. By 1880, through the utilization of a higher vacuum and the development of an entire integrated system of electric lighting, he improved his bulb’s life to 1,200 hours and began producing the invention at a rate of 130,000 bulbs per year.

In the midst of this innovation, the man who’d build the world’s longest-lasting light bulb was born.

The Shelby Electric Company

Adolphe Chaillet, c. 1890

Adolphe Chaillet was bred to make exceptional light bulbs. Born in 1867, Chaillet was constantly exposed to the burgeoning light industry in Paris, France. By age 11, he began accompanying his father, a Swedish immigrant and owner of a small light bulb company, to work. He learned quickly, garnered an interest in physics, and went on to graduate from both German and French science academies. In 1896, after spending some time designing filaments at a large German energy company, Chaillet moved to the United States.

Chaillet briefly worked for General Electric, then, riding on his prestige as a genius electrician, secured $100,000 (about $2.75 million in 2014 dollars) from investors and opened his own light bulb factory, Shelby Electric Company. While his advancements in filament technology were well-known, Chaillet still had to prove to the American public that his bulbs were the brightest and longest-lasting. In a risky maneuver, he staged a “forced life” test before the public: The leading light bulbs on the market were placed side-by-side with his, and burned at a gradually increased voltage. An 1897 volume of Western Electrician recounts what happened next:

“Lamp after lamp of various makes burned out and exploded until the laboratory was lighted alone by the Shelby lamp — not one of the Shelby lamps having been visibly injured by the extreme severity of this conclusive test.”

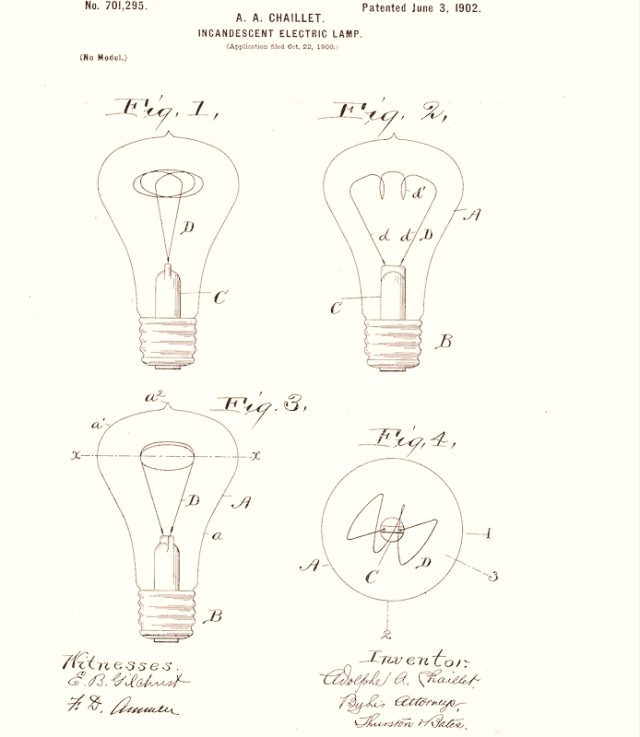

Chaillet’s original patent

The bulb’s brilliance was attributed to Chaillet’s patented coiled carbon filament, as recounted in a The Electrical Review (1902):

“The inventor’s idea, practically stated, is to flatten the coil, and also flatten the end of the globe or bulb so that the greatest intensity of light is thrown downwardly. The filament is coiled in a form which presents a loop that is elongated transversely of the axis of the lamp, or in other words, the loops are substantially elliptical, the major axis being transverse to the longitudinal axis of the lamp. The globe is likewise flattened at its tip end so that the glass wall is substantially parallel with the lower lines of the filament loops when the lamp is suspended from above.”

Citing these advancements, Shelby claimed that its bulbs lasted 30% longer and burned 20% brighter than any other lamp in the world. The company experienced explosive success: According to Western Electrician, they’d “received so many orders by the first of March [1897], that it was necessary to begin running nights and to increase the size of the factory.” By the end of the year, output doubled from 2,000 to 4,000 lamps per day, and “the difference in favor of Shelby lamps was so apparent that no doubt was left in the minds of even the most skeptical.”

Over the next decade, Shelby continued to roll out new products, but as the light bulb market expanded and new technologies emerged (tungsten filaments), the company found itself unable to make the massive monetary investment required to compete. In 1914, they were bought out by General Electric and Shelby bulbs were discontinued.

The Centennial Light

Seventy-five years later, in 1972, a fire marshall in Livermore, California informed a local paper of an oddity: A naked, Shelby light bulb hanging from the ceiling of his station had been burning continuously for decades. The bulb had long been a legend in the firehouse, but nobody knew for certain how long it had been burning, or where it came from. Mike Dunstan, a young reporter with the Tri-Valley Herald, began to investigate — and what he found was truly spectacular.

Tracing the bulb’s origins through dozens of oral narratives and written histories, Dunstan determined it had been purchased by Dennis Bernal of the Livermore Power and Water Co. (the city’s first power company) sometime in the late 1890s, then donated to the city’s fire department in 1901, when Bernal sold the company. As only 3% of American homes were lit by electricity at the time, the Shelby bulb was a hot commodity.

In its early life, the bulb, known as the “Centennial Light,” was moved around several times: It hung in a hose cart for a few months, then, after a brief stint in a garage and City Hall, it was secured at Livermore’s fire station. “It was left on 24 hours-a-day to break up the darkness so the volunteers could find their way,” then-Fire Chief Jack Baird told Dunstan. “It’s part of another era in the city’s past [and] it’s served its purpose well.”

Though Baird acknowledged that it had once been turned off for “about a week when President Roosevelt’s WPA people remodeled the fire house back in the 30s,” Guinness World Records confirmed that the hand-blown 30-watt bulb, at 71 years old, was “the oldest burning bulb in the world.” A slew of press followed, which saw it featured in Ripley’s Believe it or Not, and major news networks.

***

Aside from the 1930s fire house remodel, the bulb has only lost power a few times — most notably in 1976, when it was moved to Livermore’s new Station #6. Accompanied by a “full police and fire truck escort,” the bulb arrived with a large crowd eager to see it regain power, but, as recalled by Deputy Fire Chief Tom Brandall, “there was a little scare:”

“We got to new location and the city electrician installed the light bulb and made connection. It took about 22-23 min, and [the bulb] didn’t come back on. The crowd gasped. The city electrician grabbed the switch and jiggled it; it went on!.”

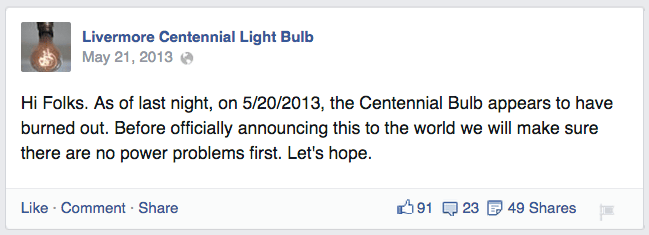

Once settled, the bulb was placed under video surveillance to ensure it was alive at all hours; in subsequent years, a live “BulbCam” was put online. Last year, the bulb’s groupies (of which there are nearly 9,000 on Facebook), received another scare when it lost light:

The Centennial Light’s Facebook page

At first it was suspected that the light had finally met its demise, but after nine and half hours, it was discovered that the bulb’s uninterrupted power supply had failed; once the power supply was bypassed, the bulb’s light returned. The 113-year-old bulb had outlived its power supply — just as it had outlived three surveillance cameras.

Today, the bulb still shines, though, as one retired fire volunteer once said, “it don’t give much light” (only about 4 watts). Owning a frail piece of history comes with great responsibility: Livermore firefighters treat the little bulb like a porcelain doll. “Nobody wants that darn bulb to go out on their watch,” once said former fire chief Stewart Gary. “If that thing goes out while I’m still chief it will be a career’s worth of bad luck.”

“They Don’t Make ‘Em Like They Used To”

Everyone from Mythbusters to NPR has speculated on the reasons for the Shelby bulb’s longevity. The answer, in short, is that it remains a mystery — Chaillet’s patent left much of his process unexplained.

Some, like UC Berkeley electrical engineering professor David Tse, outright dispel the bulb’s legitimacy. “It’s not possible,” he told the Chronicle in 2011. “It’s a prank.” Others, like engineering student Henry Slonsky, insist it’s likely due to the fact that things were once made with more care. “Back then,” he says, “they made everything way over the top.”

In 2007, Annapolis physics professor Debora M. Katz purchased an old Shelby bulb of the same vintage and make as the Centennial Light and conducted a series of experiments on it to determine its differentiation from modern bulbs. She reported her findings:

“I found the width of the filament. I compared it to the width of a modern bulb’s filament. It turns out that a modern bulb’s filament is a coil, of about 0.08 mm diameter, made up of a coiled wire about 0.01 mm thick. I didn’t know that until I looked under a microscope. The width of the Shelby bulb’s 100-year-old filament is about the same as the width of the coiled modern bulb’s filament, 0.08 mm.”

While Katz’s findings were inconclusive, she speculates that the Shelby bulb’s filament — eight times thicker than that of a modern bulb — may be integral to its longevity. Modern bulbs, she explains, use thinner tungsten filaments that put out more light (40 to 200 watts) burn hotter, and are therefore taxed more rigorously than older bulbs like the Shelby. “You can think of it as sort of an animal with a low metabolism,” she reported to the Centennial Light’s committee. “It’s giving us less energy per time, so it can keep on going longer.” Katz also adds that the bulb’s age could be, in part, contributed to the fact that it hasn’t been turned off and on a whole lot — a process which is more exhausting on a bulb than letting it run continuously (the filament needs to reheat itself, much like a car’s engine).

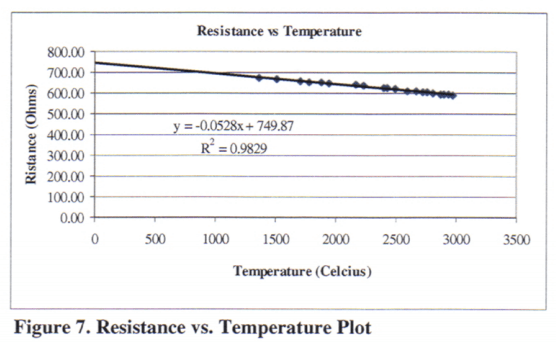

The Shelby bulb’s properties, from Felgar’s Paper

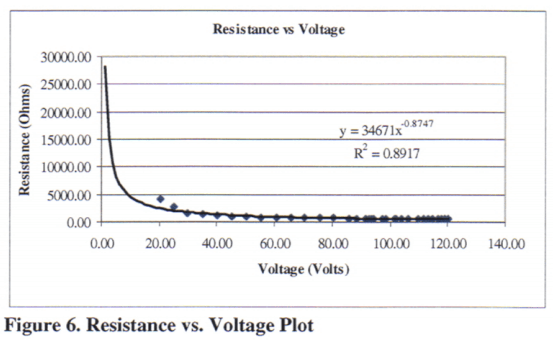

Justin Felgar, one of Katz’s students, explored the bulb further and published his findings in the 2010 paper, “The Centennial Light Filament.” Felgar found that the hotter the Shelby got the more electricity went through it — the opposite of what happens to modern tungsten filaments. To determine the Shelby filament’s exact makeup, Felgar asserts that it would be necessary to “tear one up” and run in through the Naval Academy’s particle accelerator — but it’s a costly process and has yet to be undertaken.

Ultimately, Katz and her colleagues remain uncertain. “I thought for sure all the physics must’ve been worked out,” she says, “But perhaps there’s just some fluke with that particular [bulb].” Livermore’s ex-deputy fire chief agrees. “The reality is its probably just a freak of nature,” he told NPR in 2003, “just one in a million light bulbs thats just going to keep going and going.”

The Lightbulb Cartel

Today, the average incandescent bulb lasts about 1,500 hours; even top-of-the-line LED bulbs, at $25 each, last 30,000 hours. Regardless of the Centennial Bulb’s secret formula, it has burned for 113 years — nearly 1 million hours. So where did we go wrong with light bulb technology?

Light bulb companies like Shelby once prided themselves on longevity — so much so, that the durability of their products was the central focus of marketing campaigns. But by the mid-1920s, business attitudes began to shift, and a new rhetoric prevailed: “A product that refuses to wear out is a tragedy of business.” This line of thought, termed “planned obsolescence,” endorsed intentionally shortening a product’s lifespan to entice swifter replacement.

In 1921, multinational lighting manufacturer Osram formed the “Internationale Glühlampen Preisvereinigung” (International Association of Light Bulb Prices) to regulate prices and limit competition. General Electric soon reacted by founding the “International General Electric Company” in Paris. Together, these organizations traded patents and sales information to get a stronghold on the light bulb market.

In 1924, Osram, Philips, General Electric, and other major electric companies met and formed the Phoebus Cartel under the public guise that they were cooperating to standardize light bulbs. Instead, they purportedly began to engage in planned obsolescence. To achieve this the companies agreed to limit the life expectancy of light bulbs at 1,000 hours — less than Edison’s bulbs had achieved (1,200 hours) decades before; any company that produced a bulb exceeding 1,000 hours in life would be fined.

Until disbanding during World War II, the cartel supposedly halted research, preventing the advancement of the longer-lasting light bulb for nearly twenty years.

***

Whether or not planned obsolescence is still on the agenda of light bulb manufacturers today is highly debatable, and there exists no definitive proof. In any case, incandescent bulbs are being phased out worldwide: Since Brazil and Venezuela began the trend in 2005, many countries have followed suit (European Union, Switzerland, and Australia in 2009; Argentina and Russia in 2012; the United States, Canada, Mexico, Malaysia, and South Korea in 2014).

As more efficient technologies have surfaced (halogen, LED, compact fluorescent lights, magnetic induction lights), the old filament-based bulbs have become a relic of the past. But perched up in the white ceiling of Livermore’s Station #6, the granddaddy of old-school bulbs is as relevant as ever — and refuses to bite the dust.

If you enjoyed this post, you’ll be mildly amused by our book → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.