Researchers can’t ask cavemen about their sleeping habits. If you want to get a sense of a paleo sleep schedule, the best you can do is find a place without Netflix, iPhones, streetlights, and 18-hour work days.

That’s why sleep researchers recently asked 94 people who live in preindustrial societies to wear Actiwatches—wearable devices that measure “activity, sleep, wake, and light-exposure data.” Those 94 people include Hadzas and Ju/’hoansis, hunter-gatherers who live along Lake Eyasi in Tanzania and the deserts of southern Africa, and Tsimanes, hunter-horticulturalists who live in lowland Bolivia.

“People like to complain that modern life is ruining sleep, but they’re just saying: Kids today!” researcher Jerome Siegel explained in an interview. “It’s a perennial complaint, but you need data to know if it’s true.”

Siegel and his peers simply want to know more about the sleep habits of people whose unelectrified lives more closely resemble our past. But given that Siegel’s research subjects don’t have a word for insomnia, commonly live into their “60s, 70s, 80s, and beyond,” and never exhibit obesity, it’s tempting to view them as living in some sort of preindustrial Eden of sleep.

A common reaction among the public is to ask whether we should copy them. A more interesting question is why we’d want to.

The Re-Discovery of Sleep

William Dement is a professor who made the connection between rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and dreaming. Roger Ekirch is a historian and the author of At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past. Both are experts on sleep, and both of them agree: their fields don’t pay enough attention to sleep.

Their comments are not the mere complaints of professionals convinced that everyone should care about their work. As Ekirch wrote in 2001, “So ingrained has been the historical indifference toward sleep that such elementary matters as the time and length of slumber before the nineteenth century remain an enigma.”

Ekirch’s investigation of sleep kept turning up odd mentions in plays, poems, and diaries from preindustrial Europe of “first sleep” and “second sleep.” In Descriptions of England, clergyman William Harrison wrote in 1577 of “the dull or dead of the night, which is midnight, when men be in their first or dead sleep.” In The Canterbury Tales, a character wakes up in the very early morning “after her first sleep.”

Translators and historians have interpreted first and second sleeps as “the first moments of sleep” or “early slumbers.” Ekirch’s dutiful digging through historical records, however, revealed that Europeans’ sleep was once segmented. They commonly woke up in the middle of the night, spent roughly an hour discussing the children with a spouse, doing chores, thinking about their dreams, or having sex, and then slept again until morning.

As Ekirch tracked down references of first and second sleeps, Dr. Thomas Wehr watched his research participants undergo segmented sleep. In order to mimic a long winter night, Wehr had put his subjects in a dark lab for 14 hours each night. After several weeks, they started sleeping in two periods separated by a wakeful hour or two. Looking at his subjects’ brain waves and hormone levels during the wakeful period, Dr. Wehr likened it to “a state of meditation.” This sounded familiar to Ekirch, who had read dozens of accounts from artists and intellectuals that this inter-sleep period was great for contemplation.

By finding references to segmented sleep throughout time (in the Aeneid and the Odyssey) and place (in villages visited by anthropologists), Ekirch speculated that a single block of unbroken sleep was a recent development. Wehr asked whether this wakeful period might have once been “a nightly occurrence.” Both pointed to the light bulb and modern life as the death of segmented sleep.

***

The work of sleep researchers like William Dement has provided a scientific foundation for this sense—shared by busy office workers—that electric lights and hectic schedules have changed how we sleep, likely for the worse.

Dr. Dement spent years as a popular professor at Stanford who taught his students to yell, “Drowsiness is red alert!” In experiments, Dr. Dement measured how long it took Stanford students and other research subjects to fall asleep if they lay down in a dark place during the day—a proxy for sleepiness.

By monitoring these students and mandating that they sleep more each night, Dement found that it took the students longer and longer to fall asleep during the day. Once they caught up on sleep—and paid off what Dement dubbed a “sleep debt” from sleeping too little in the past—students reached an equilibrium and reported feeling much better rested and less fatigued. Since sleeping 8 hours each night allowed most of his subjects to maintain this equilibrium, Dement’s studies represent an important foundation for the recommendation to get 8 hours of sleep.

If you’ve ever wondered who is making you feel guilty about not sleeping enough, you can blame, among others, a white-haired Stanford professor who believes sleep is so important that he gives students extra credit for falling asleep in class.

What is Normal Sleep?

An easy interpretation of sleep research is that modern life has negatively disrupted our sleep. Yet studies of preindustrial societies defy simple explanations of a sleep-paradise lost.

When Siegel and his peers reviewed the data from their 94 test subjects who live hunter-gatherer, light bulb-free lifestyles, the researchers found that they slept 5.7 to 7.1 hours per day. They did not observe segmented sleep; they found that the hunter-gatherers went to bed several hours after sunset and rarely napped; and they describe the average nightly sleep duration of 6.4 hours as “near the low end of those [of] industrial societies.”

“Sleep in these traditional human groups,” Siegel and co. conclude, “is more similar to sleep in industrial societies than has been assumed.” They speculate that segmented sleep may actually be a more recent development (from the perspective of a paleontologist) that arose when humans migrated out of Africa to higher latitudes that experience long winter nights.

Ekirch’s exploration of sleep in Europe’s past also demonstrates that our worries about undersleeping are nothing new. In one diary entry, he notes, a shopkeeper who had expressed his determination to get 7 to 8 hours of sleep recalls returning home at 3 a.m. “not very sober” and laments, “Oh, liquor, what extravagances does it make us commit!” Britons drank alcohol and consumed opiates as sleep aids in the 17th century, and aristocrats called their (sleep-deprived) servants slothful for constantly falling asleep on the job.

Finding a normal or ideal period to model our sleep after is made more difficult by the fact that people seem to require different amounts of sleep. Children and teenagers need more sleep than adults and seniors. Studies that subject people to sleep deprivation find that people’s ability to handle less sleep varies widely—a trait likely determined by genetics.

The search for a prehistoric sleep pattern, and any attempt to mimic it, also suffers from the same problems as the paleo diet.

Critics of the paleo diet point out that cavemen had terrible diets. Before humans cultivated better food and achieved food security, vegetables were skimpy, unappetizing, and of little nutritional value, and balanced diets were rare.

Similarly, anyone promoting paleo sleep would be thrown off by Ekirch’s descriptions of historic sleeping conditions: In 16th century Britain, peasants searched their bedding for fleas and bedbugs each night and, in order to stay warm, slept with livestock and endured their feces and urine.

Scientists who study isolated groups—like Siegel and his peers with the Hadzas and Ju/’hoansis—are investigating how sleep may have looked in the past. They’re not looking for a model. But it’s worth noting that many of these remaining hunter-gatherers are impoverished or persecuted minorities. One group visited by anthropologists, the Toraja of Indonesia, do not exhibit segmented sleep or a single block of sleep. They wake up constantly throughout the night because “they sleep on the floor together in groups, sharing blankets and huddling close for warmth.”

Another critique of the paleo diet is that paleolithic humans’ diets varied by “season, geography, and opportunity.”

Our best proxies of paleo sleepers exhibit similar diversity. Some enjoy segmented sleep, others sleep in one block like modern sleepers, and some groups, like the Toraja, exhibit punctuated sleep. The three groups studied by Siegel and his co-writers only slept 6.4 hours per night. But in a rebuttal in The Atlantic, sleep researcher Horacio de la Iglesia noted that other hunter-gatherer groups sleep for as many as 9 hours. When he studied two such neighboring communities, he found that one that gained access to electric lights slept an hour less each day.

If someone suggests the paleo sleep schedule, you should ask, “Which one?”

Why Sleep?

When we look at isolated societies or in history books for examples of more paleo-like sleep, we do so with a particular, modern perspective: that sleep is a problem to be managed or a tool that wards off drowsiness and makes us productive.

We see this in the work of Dr. Dement, who describes sleep as a key to productivity and has investigated how extra sleep allows Stanford basketball players to achieve personal bests in free throw accuracy. It’s also the foundation of the $55 billion sleep aid industry. Even contrarians who dispute the findings of researchers like Dr. Dement do so by pointing to studies that seem to show people cutting back on sleep without suffering from fatigue or a drop in productivity.

But if there is anything to learn from paleo sleep, it’s not how many hours we should sleep or the importance of naps. It’s that there are ways to think about sleep other than as an off switch.

In many societies without electric lights, being awoken is not an obstacle to sleep. It’s a key reason why dreams are part of their lives. “In traditional non-Western societies like the Toraja,” anthropologist Tanya Marie Luhrmann writes, “what happens at night really matters. People pay close attention to their dreams, and because they are awakened more often, they have more opportunity to remember them.” Ekirch notes that Europeans once spent their inter-sleep period discussing dreams, and that the Alorese of the West Indies wake each other every night to share their reveries.

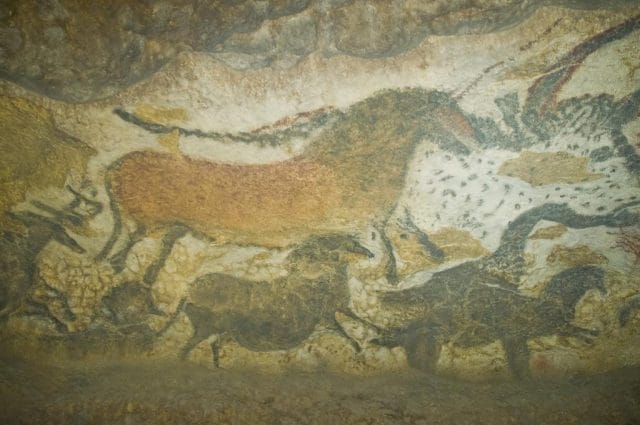

Was this artist well rested? Photo by Jack Versloot

When dreams are not forgotten, they influence life. Ekirch explains that art from preindustrial Britain displayed men and women awake in bed and reacting forcefully to their dreams. For this reason, ladies placed cakes beneath their pillows to incite sweet dreams, and peasants used charms to prevent nightmares.

Due to “continuous disruptions,” wrote anthropologist Eduardo Kohn, who studied a community in the Amazon where the cold and sounds of nature regularly woke villagers, “dreams spill into wakefulness and wakefulness into dreams in a way that entangles them both.”

This may help explain the dominant influence that spirituality, religion, and superstition once held. The British letters studied by Ekirch reveal that people severed friendships or began romances based on their dreams. Anthropologists and historians have chronicled how people ascribed omens, spiritual visions, and visits from the dead to their dreams or bouts of wakefulness in the middle of the night.

Modern readers may not miss superstitious interpretations of dreams and half-awake visions. But perhaps we should envy the bouts of wakefulness and the inter-sleep period that 16th and 17th century artists and scholars described as a particularly peaceful, contemplative period. When Dr. Wehr observed that the research participants he subjected to 14 hours of darkness started to exhibit segmented sleep, he noted that their brain waves and hormone levels resembled meditation when they woke.

“Perhaps what those who meditate today are seeking,” he mused, “is a state that our ancestors would have considered their birthright, a nightly occurrence.”

![]()

Our next post investigates the world of for-profit snuggling.

To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. You can follow him on Twitter at @amayyasi.

The lead photo for this article is from Year One, a film by Apatow Productions.