Mariana Stark, an Englishwoman who wrote travel guidebooks in the 1820s, had a brilliant idea.

In Stark’s time, tourism for the British meant going to mainland Europe to look at art. Travel was an educational experience for the upper classes in which they would see the best of “Western Civilization.” But how were tourists to know what was the very best?

Stark’s solution: Exclamation marks.

Stark writes in the introduction to her guidebook, “In the following pages the Reader will find that several of these works of Art are distinguished, according to their reputed merit, by one or more exclamation-points.” Venus and Cupid by Rembrandt: one exclamation point. Le Belle Jardeiniere by Raphael: two exclamation points. Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa: curiously, no exclamation points.

Stark’s use of exclamation marks — the precursor to the star ratings of today — came at the dawn of the modern guidebook.

The physical guidebook, developed by Stark and others in the 19th Century, has had a good run. Millions of people have traveled the world with a guidebook in hand. But the guidebook’s nearly two-hundred year run may be coming to an end. Over the last decade, guidebook sales have declined, due in large part to the increasing availability of the Internet and sites like Google Maps, Yelp and Wikitravel.

We explore the history of how the guidebook grew into its current form, and whether technology has made it obsolete.

The Dawn of the Guidebook

Travel literature, writing that concerns visits to foreign lands, goes back thousands of years. The Greek author Pausanias wrote about his travels through Greece in the 2nd Century, Marco Polo about Asia in the 13th, and Ibn Battuta about almost the entire Eastern Hemisphere in the 14th. Readers took in their experiences in lieu of traveling themselves. Travel was exceedingly expensive, dangerous and time consuming, and it was only available to an adventurous few.

Modern tourism, at least in its Western form, began with the Grand Tour. The Grand Tour, the emergence of which coincided with the Enlightenment, became a ritual for upper-class Brits beginning in the late 1600s. These travellers would set out for Italy—and perhaps a few other countries—to see the architecture of Ancient Rome, ponder the art of the Renaissance, and rub noses with the local aristocracy. It was seen as declasse among the elites to not have done the Tour. The noted intellectual Samuel Johnson wrote in the 1700s, “a man who has not been in Italy is always conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see.”

In the early days of the Grand Tour, guidebooks did not play a large role. Tourists generally had a Cicerone, a personal guide who arranged everything for them. But by the 1800s, due to industrialization and steam-powered transportation, travel became cheaper and open to a larger pool of people.

It was in this period of the democratization of travel that the modern Guidebook emerged. Books written for travellers prior to 1800, like the The Gentleman’s Pocket Companion, for Travelling Into Foreign Parts and The Voyage Of Italy, Or A Compleat Journey Through Italy, were nearer to travel literature. They were mostly written in the first person, and primarily filled with subjective opinions about sites that writer had visited.

The innovation of 19th Century guidebook writers was putting the practical concerns of the traveller front and center. Many of the new, slightly less wealthy, tourists could not afford a personal guide to handle logistics. The counsel they received from a written guide on the challenging aspects of travelling were invaluable.

Mariana Stark, a “transitional figure” in the growth of the Guidebook, was one of the first to focus on providing practical information. In her 1826 guide, Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent, Stark provides itineraries for travelling in Western European countries, along with suggestions about the best mode of travel and places to stay. Her accommodation advice would not satisfy modern travelers. “Le Lion d’Or is a good inn,” she wrote in one passage. “La Croix Blanche, though less good, is tolerable.”

Stark also includes brief and informative descriptions of the main sites in each city. Her writing is similar to what you might find today in the Lonely Planet. Below is an excerpt on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris:

Yet Stark’s guidebooks were still antiquated in their use of the first person and relatively disorganized presentation of information. The modern guidebook truly arrived a decade later.

The Modernizers

In 1836, John Murray III started publishing Murray’s Handbooks for Travellers, his series that revolutionized the guidebook. The series is still published today as Blue Guides.

Murray brought the “rational planning” mindset of the industrial revolution to guidebook writing, providing the reader with never before seen levels of detail. His goal was to collect “all the facts, information, statistics, &.c, which an English tourist would be likely to require or find useful.”

Murray’s Handbooks included instructions for getting passports, advice on obtaining foreign currency, train schedules, and recommendations for how much luggage to bring. He even had thoughts on the the potability of the water. “In the provinces of Holland, bordering on the seas, that water is generally very bad, not drinkable; and strangers should be careful to avoid it altogether, except externally,” advises Murray, “or they may suffer from bowel complaints, and be delayed on their journey.”

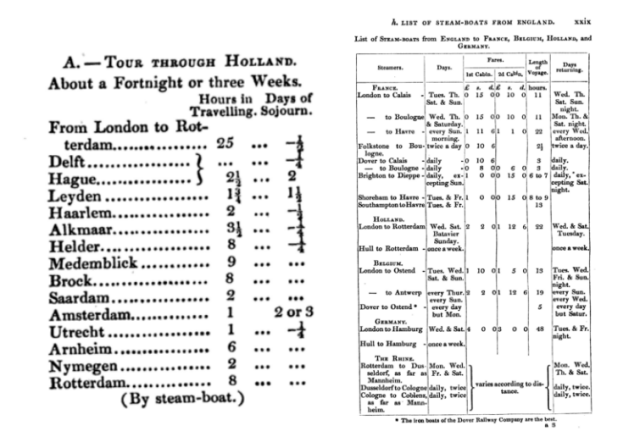

A suggested itinerary for Holland along with a train schedule from Murray’s “A Handbook for Travellers on the Continent.”

The tone of Murray’s writing is sharper than what is generally found in contemporary guidebooks. He seems equally intrigued and bewildered by the places he describes. Murray calls Holland “hardly endurable” as a place to live, but so peculiar in its charms that it is “too strange to fatigue.”

Much of the advice in Murray’s Handbooks still applies. He recommends taking “as little baggage as possible” and says that “No one should think of travelling before he has made some acquaintance with the language of the country.” Murray’s caution about rapacious agents who ambush newly arrived tourist still rings true for the intrepid traveller:

When the steam-boat reaches its destined port, the shore is usually beset by a crowd of clamorous agents from the different hotels, each vociferating the name and praises of that for which he is employed, stunning the distracted stranger with their cries, and nearly scratching his face with their proffered cards. The only mode of rescuing himself from these tormentors, who often beset him a dozen at a time, is to make up his mind beforehand to what hotel he will go, and to name it at once.

In the introduction to the 1845 edition of the Handbook For Travellers on the Continent, Murray refers to “an intelligent bookseller” in Germany named Karl Baedeker, who Murray was indebted to for translating his guide into German and improving its accuracy. Karl Baedeker would go on to become one of the few people who was arguably even more influential in the development of guidebooks than Murray himself.

A map of Waterloo from Karl Baedeker’s Guidebook for “Belgium and Holland”

Baedeker was a bookshop owner German town of Essen. In the early 1830s, when a publishing house in the city went bankrupt, Baedeker bought out the firm. One of that firm’s best sellers was a guidebook, A Guide to the Rhine – A Rhine Journey from Mainz to Cologne. The author of that book died, and the travel-loving Baedeker decided he would update it himself.

In the course of bringing of A Guide to the Rhine up to date, Baedeker had a similar realization to Murray. He was struck by how little of the information that would be most useful to a tourist was actually in the book. Herbert Warren Wind wrote in a 1975 New Yorker article that in addition to history and descriptions of the landscape, Baedeker thought a guidebook should contain information like “the most comfortable hotels in the key cities and the prices of the rooms, the restaurants that gave the traveller the best value for his money, the easiest way to reach little-known, out-of-the-way towns and villages that had something special to offer…”

Baedeker’s update of A Guide to the Rhine was published in 1839, and the resulting book was so completely different from the original that he published it under his own name. He followed this by creating guides for Holland and Belgium. They were a grand success.

Baedeker’s books became so popular that, for a time, the term Baedeker became synonymous with guidebooks (like Kleenex and tissue paper). Baedeker’s works were known for their incredible detail, accuracy and dedication to assuring that his readers were not taken advantage of financially. The books were also renowned for their excellent maps. Baedeker’s were used by British officers in the Middle East during World War I and by the Germans in World War II. Over time, Baedeker’s were published in most major languages.

Perhaps the most influential aspect of Baedeker’s work was his prose style. His writing is clear and concise, and whereas John Murray was cantankerous, Baedeker exhibited a great pleasure in travel. Almost all of the modern guidebooks ape his amiable but direct style. Baedeker’s description of the Italian city of Siena is a good example:

Siena possesses a population of 24,000 souls, a university founded in 1203, an archbishop, several libraries and scientific societies, a thriving trade and manufactories, and is one of the most animated and agreeable towns in Tuscany. The climate is healthy, the atmosphere in summer being tempered by the lofty situation, the language and manners of the inhabitants pleasing and prepossessing.

The guidebooks written by Baedeker are remarkably similar to today’s.

The Guidebook’s Halcyon Days

The 20th Century was the heyday of the Guidebook. The rise of the middle class and air travel made tourism accessible to a much larger part of the world’s population, and these greenhorns wanted guidebooks. By 2000, the guidebook had grown into a $200 million industry.

In addition to Baedekers and Blue Guides, the market was flooded with other names. Early guides include Michelin, Fodor’s, and Frommer’s. With a larger and more diverse group of travellers came specialization. Michelin distinguished itself by its ranking of restaurants, Frommer’s by its focus on budget travel, and Fodor’s by its focus on culture. Eugene Fodor wrote in the introduction to a guidebook of Italy, “Rome contains not only magnificent monuments, but also Italians.”

Later in the 20th Century, “backpacker” focused guidebooks like Let’s Go, Lonely Planet and Rough Guides emerged. These new books were particularly focused on young people looking for a bargain, and they were filled with advice for getting off the beaten path. Harvard University students started Let’s Go, the first “backpacker” guide, in the 1960s. Let’s Go continues to be written by students to this day. Lonely Planet, which followed Let’s Go, became the largest Guidebook publisher in the world.

Guidebooks also became more niche in geography and area of interest. Guides appeared for specific cities and regions, and for those looking for outdoor adventures. Jane Austen aficionados and zoo lovers even got their own travel books.

The forecast for the physical guidebook looked rosy at the turn of millennium. But the Internet and financial crash changed everything.

The Death of the Guidebook?

In 2008, guidebook sales reached an all-time high. The year before, the couple that founded Lonely Planet sold the company to the BBC for nearly $270 million.

It was bad timing for the BBC. The next five years were the guidebook industry’s worst since its inception. When the BBC sold the company in 2013 to NC2 Communications, it received $137 million.

For many, this signalled the “death knell” of the traditional guidebook. An outpouring of nostalgia flowed on to Twitter.

— Ina (@EirysX) August 4, 2013

What happened? A market crash and the Internet.

The 2008 recession was terrible for the publishing industry in general, but especially bad for the guidebook industry. Tourism decreased, and when people did travel, they were less likely to splurge on a guidebook.

Instead, travellers relied on free online resources like Tripadvisor or Wikivoyage. Eric Kettunun, the former director of Lonely Planet, said of the decline, “It was the ease at which travelers could access destination content online, especially ‘perishable’ info like rates at hotels, prices at restaurants, etc.” The improved Internet access and battery power of smartphones made going without a guidebook increasingly sensible. Lost and don’t know the language? No need for a map from a guidebook; a tourist could just look up directions on Google Maps.

The combined sales of the 5 largest guidebook publishers in the United States fell from $125 to $78 million between 2007 and 2012: a 40% decline. The following chart shows the sales numbers for major publishers in the United States. It includes digital sales.

Data: Skift.com

Guidebooks publishers reacted slowly to the Internet. For example, Frommer’s did not dedicate any staff to developing new digital products. Generally, the companies presumed that people cared more about receiving curated information, not trusting what they found online. Like many interested that thought they were insulated from the disruption of the Internet, they were wrong (see hotels and taxis).

After this significant downturn, however, the guidebook may be making a small comeback. Nielsen Bookscan data shows that after years of decline, guidebook sales in the United States increased in 2014 by 3%.

The primary reason for this uptick is increased travel, particularly tourism, due to better economic conditions. In addition, many publishers have improved their online presence and are generating more revenues from downloadable content.

Some in the publishing industry believe there is something deeper at work: that the shine has come off online reviews and people are returning to the physical objects they love. Lorrain Shanley, formerly of the publisher HarperCollins, believes that guidebooks are similar to cookbooks, which have continued to have strong sales. “The emotional relationship between the reader and the travel book is like the emotional relationship between a reader and a favorite cookbook author,” she says. “It summons up a lifestyle to which you have an attachment.”

Certainly, nostalgia and affection will keep some people coming back to the guidebook, but it’s not a long term solution for the industry. Modern guidebook publishers will need to channel the innovative spirit of those who created the genre, and their obsession for figuring out what might improve the travellers’ experience. If not, the guidebook’s best days have past.

***

For our next post, we explain why “picking the low-hanging fruit” is bullshit — at least, according to actual fruit pickers. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Dan Kopf; follow him on Twitter here.