“I think this theory checks out. I was very unpopular with the opposite sex in high school and I ended up valedictorian”

~ Rohin Dhar, Priceonomics CEO

![]()

When you are in high school, it feels very important to be popular. Given the amount of hormones floating around, it feels particularly important to be popular with the opposite sex (especially if you’re a straight teenager). Popularity with the opposite sex is key to unlocking many of teenagehoods most stressful rites: finding a date to the prom, getting invited to a party, or landing a girlfriend or boyfriend.

But if you’re not popular with the opposite sex, what’s the silver lining? Good grades, as it turns out.

According to a recently published study in the American Economic Journal of Applied Economics, a larger number of opposite gender friends may drag down your grades. The myth of the sexless but brainy high school nerd appears to be true. While all the cool kids are out partying and dating, the nerds are getting ahead academically.

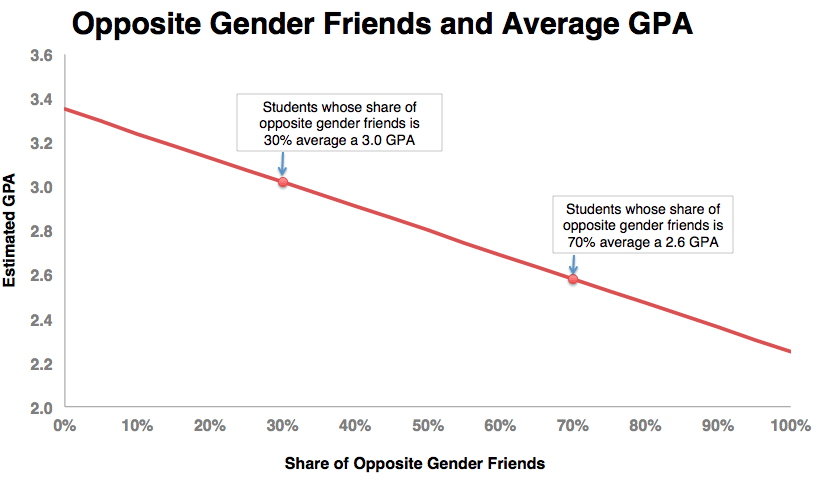

The study, cheekily titled, “The Girl Next Door: The Effect of Opposite Gender Friends on High School Achievement,” uses data from a nationally representative survey of students from grades 7 to 12, to assert that students with more friends of the opposite gender perform worse academically. And this is no small effect. The results from the study suggest that, on average, if people of the opposite gender make up 70% of a student’s friend group, that student will have a GPA 0.4 lower than if only 30% of their friends were of the opposite gender.

The study is also full of great nuggets on how adolescents of either gender interact with their friends, and other social behaviors. Which gender talks on the phone with more of their friends? What proportion of 7th-12th graders report smoking cigarettes, or ever having been in a relationship?

****

Dr. Andrew J. Hill, the author of the “Girl Next Door” study and an Economics professor at the University of Southern California, has long been interested on the effects of gender interaction in schools. “I grew up in a family of educators surrounded by opinions of how the interactions between boys and girls at school affect outcomes.” he explained. “But it seemed these were often not based on any real evidence.” Hill went about finding that evidence.

Hill’s study uses data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, a survey of over 20,000 students from 80 schools in 1994-1995. Students interviewed were asked to nominate up to 5 female friends and 5 male friends. The average number of friends nominated was 2.6, with 62% of these friends of the same gender.

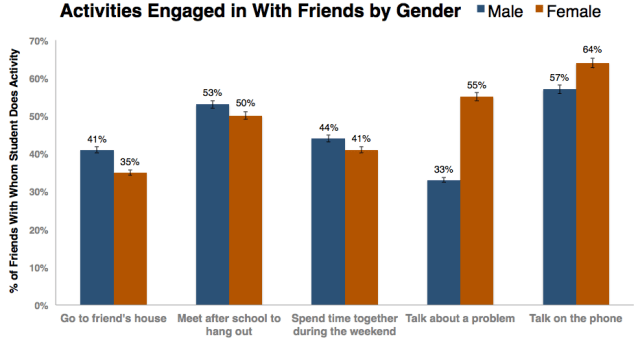

The following chart shows the activities male and female schoolmates reported engaging in with their friends:

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Hill

***

The result of the study is straightforward: additional opposite gender friends have a negative impact on grades. But the methodology to reach this result is relatively complex. The main complexity arises from the fact that it is difficult to isolate the impact of having more opposite gender friends. Hill explains:

“…Lots of things cause people to become friends, so you cannot just compare the GPA of students with 70% opposite gender friends and 30% opposite gender friends and argue that this difference is caused by the different share of opposite gender friends. Many other factors may also differ between those individuals.”

Hill did not just want to look at the correlation of opposite gender friends and grades, he wanted to make a causal argument. If you randomly introduce more opposite gender friends into someone’s life, how does this affect academic performance?

In order to make this causal argument about the effect of opposite gender friends on academic performance, Hill used a clever social science trick. He found that the number of opposite gender schoolmates that lived near a student highly correlated to the number of opposite gender friends they had. Unlike the factors determining who your friends are, the number of opposite gender schoolmates in the neighborhood is random (Hill demonstrates this). It then follows that if students who have more opposite gender schoolmates in the neighborhood have a worse GPA, this can be attributed to an increased share of opposite gender friends.

The estimated impact on academic outcomes is substantial. The primary result of the paper is that a 50% increase in the number of opposite gender neighbors, on average, causes a 0.5 lower GPA. It’s a sizable enough effect that tiger mothers should take note. The study is based on a sample, so it is certainly possible that the effect is smaller or larger than reported, but a real and notable effect is likely.

The following chart displays the average GPA for students with different shares of opposite gender friends:

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Hill

***

In the paper, Hill explores the mechanisms by which opposite gender friends might affect achievement at school. He analyzed the impact of opposite gender friends on classroom behaviors, such as “Trouble paying attention in class” and “Trouble getting along with the teacher.” The analysis showed a strongly negative relationship between a higher proportion of opposite gender friends and both of these classroom problems.

Hill also looked at issues outside of class like “Trouble getting homework done” and “Trouble with other students.” The relationship of additional opposite gender friends was also negative for these issues, but the strength of the relationship was significantly weaker. Using these finding as evidence, Hill conjectures that the impact of opposite gender friends is greater within school than out of school.

Another possible mechanism through which additional opposite gender friends might lead to worse grades is the increased likelihood of being in a relationship. The study shows that a 10% absolute increase in the number of opposite sex friends is related to a 9% higher likelihood of being in a relationship. Although this study cannot prove that being in a relationship is bad for academics, Hill speculates, “High school romantic relationships may reduce both the quality and quantity of homework and studying if students spend time with their romantic partners, as well as be distracting in the classroom.”

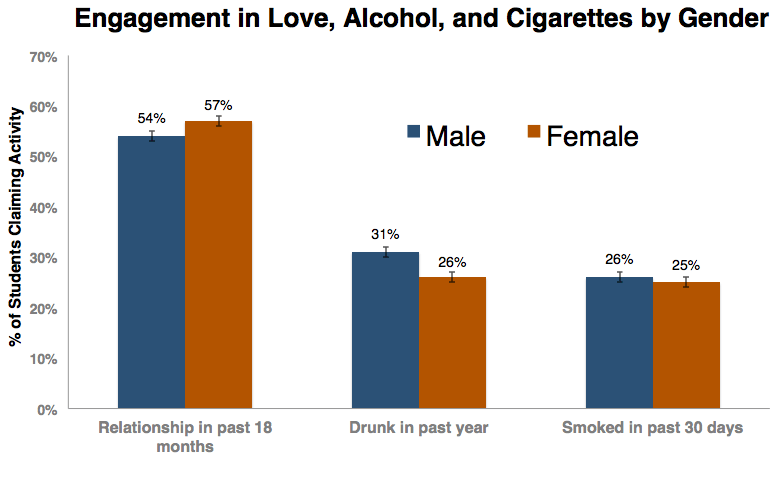

The following chart displays some of the behaviors that were examined in the paper by gender:

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Hill

***

At the beginning of Hill’s paper, he poses the question, “Are opposite gender friends in high school a distraction or do they promote better academic achievement?” This study affirmatively comes down on the side of “distraction.” Receiving little attention from the opposite sex might not have felt good, but at least it was probably good for your grades.

![]()

This post was written by Dan Kopf; follow him on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.