Colin Arisman overlooking the Sierras near the summit of Mt. Whitney

Last week, hundreds of hikers gathered in Campo, a tiny town resting on the border of California and Mexico, and set off northbound to tackle one of the longest, toughest trails in America.

Stretching 2,650 miles from Mexico to Canada, the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) meanders through harsh desert terrain, roller coasters up and down 13,000-foot Sierra peaks, and winds its way through the vast, pristine wildernesses of Oregon and Washington. In total, it crosses 25 national forests and 7 national parks, all of which greatly vary in temperature, terrain, and climate.

For those seeking to “through-hike” the trail — that is, hike it from end-to-end in a single trip — the journey will take 135 to 150 days to complete. Along the way, a hiker will wear through 4 or 5 pairs of shoes, consume some 600,000 calories (mostly in the form of energy bars and freeze-dried foods), and take 6 million steps. It’s not an undertaking for the weak-willed: less than 50% who set out to reach Canada make it there — and those who do must maintain a 20-25 mile per day pace to beat the early snowfall in Northern Washington.

The 2,650-Mile Pacific Crest Trail; via Colin Arisman, Illustration: Susan Abbott

Despite these challenges, the PCT offers something that civilization often lacks: solitude, time for inner reflection, a chance to regenerate one’s soul.

Twenty-six year old Colin Arisman is well-aware of the trail’s healing powers. After graduating college, the nomadic Vermonter felt lost, self-aware, and unsure about how to proceed in life. As his friends settled into jobs as accountants, salesmen, and contractors, he dropped off the grid and set off on the trail — not just to experience it, but to film it.

***

In April 2013, Colin Arisman boarded a plane from Burlington, Vermont to San Diego, California. He was beardless and short-haired then, vaguely aware of the journey ahead. He carried only a lightweight backpack full of the prerequisites of a long hike: a sleeping bag, a tarp, a water filter, a stove he’d crafted from a can of cat food.

A few years earlier, while miserably sick in an Ecuador hostel, he’d randomly come across a hiker’s guide to the Pacific Crest Trail while surfing the Internet. As he scrolled through the photos, and read about the man’s voyage, he knew it was something he had to do. After returning and finishing up school, he began to plan his trip.

Colin was no stranger to multi-day hikes. “My dad hiked the Long Trail [a 272-mile trail across Vermont] in the 70s,” he says. “I grew up thinking that was pretty cool, and I ended up doing it myself in college.” But he was also well aware that the PCT (10 times longer, and at much higher altitudes than the Long Trail) would be an entirely different beast — especially since he planned to film his journey.

Colin (on his dad’s back), “hiking” Vermont’s Long Trail as a youngster; Colin Arisman

“When we were preparing for the hike, we were looking for videos of the trail online; most were pretty low quality, and just focused on logistics, and the nerdy hiker side of it,” he says. “They lacked emotionally compelling, cinematic shots of the trail. So, we decided to make something available to the public.”

The PCT is not an especially cheap undertaking. The average hiker spends $4,000 to $8,000 hiking the trail, most of which goes toward gear and food. Colin, who had to also invest in film equipment, turned to Kickstarter for support. His proposal — to capture “the ebb and flow of the hike” in visual format — won over a few dozen supporters: in 30 days, he raised $3,140.

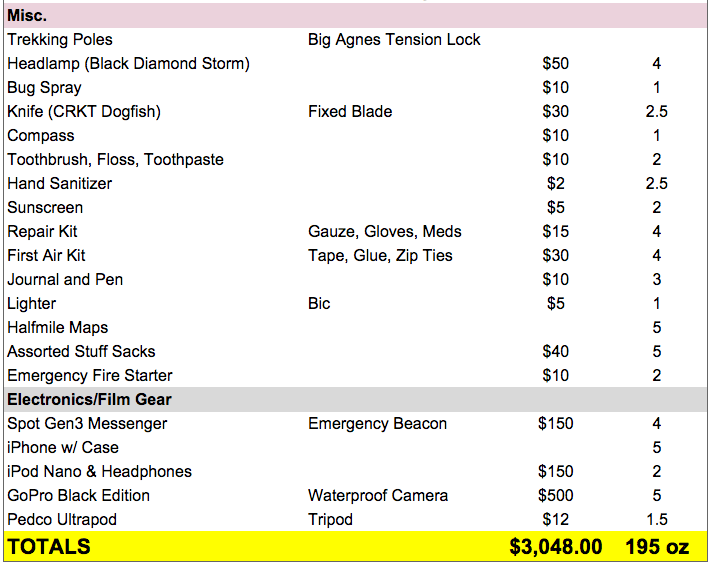

Previous efforts to film a PCT through-hike had been thwarted by the weight of equipment; Colin knew he had to keep his rig light. With his fundraised money, he bought two cameras (a Sony RX100 and a GoPro Hero 3), plenty of extra batteries, and a lightweight tripod:

“I looked specifically for gear with best ratio of sensor size (which is a good indicator of the power/quality of the camera) to weight. Both cameras were really light weight — less than half a pound — but capable of shooting really good video. We didn’t bring standard film equipment; we worked around the system, and improvised a lot.”

He spent a few months researching the logistics of the hike and putting together his gear, then, with his long-time friend Casey (“the only person crazy enough to come with [him]”), headed out West.

Colin’s PCT gear list; this “base weight” of 12lbs., 3oz. does not include consumables (food and water); during a typical day, Colin carried 2 liters of water and 3 days worth of food, and his total pack weight was 24 pounds.

The duo arrived in Campo, the trail’s Southern terminus on the Mexico-U.S. border, on April 19, 2013, about a week before the crowds amassed, and embarked on the first “phase” of the trail — a 700-mile stretch through the desert

Sparsely dotted with chaparral and tumbleweeds, the barren path crawls through the San Jacinto Mountains, the San Andreas Fault Zone, and the western arm of the Mojave Desert. Hikers endure rattlesnakes, long, water-less stretches, and temperatures over 100 degrees F. Shade is a rare commodity.

“We started out hiking all day, but the sun wore us out pretty quickly,” says Colin. “Eventually, we just found shade during the day and hiked through the nights.”

A few night shots from the desert leg of the PCT; Colin Arisman

Arriving at Kennedy Meadows marked a new stretch of land for Colin and Casey: the Sierra Nevada.

Unlike the dry, unforgiving terrain that precedes them, the Sierras are dotted with a myriad of lakes, streams, and rivers. Towering granite spires intermingle with meadows and conifer forests, and the trail winds up and over 10,000-foot peaks, providing sweeping views of carved-out valleys:

Casey overlooks the Sierras; Colin Arisman

Marmots — funny, plump little creatures intent on stealing nuggets of trail mix — pop their heads out from beneath grey rocks; coyotes howl in packs at the moon; black bears, deer, coyote, and cougars lurk behind trees and seldomly present themselves. It is an environment that is at once ripe with life and starkly solitary.

“When you think of wilderness, you think of isolation — but really, it’s a community that’s very different than our normal definition of the word,” explains Colin. “The PCT is a linear community, and as such, there are a lot of random, fleeting encounters along the way.”

In the wild, adds Colin, everyone has a story.

“The trail is a microcosm of society: you’ll meet professors, people who dropped out of high school, 13-year-olds, 70-year-olds, professionals, dirtbags,” he says. “And being in nature makes us more comfortable being vulnerable with people. In the city, you’re over-stimulated with interactions; when you’re out on the trail, you’re starved for it.”

In the Sierras, Colin came across a variety of these characters: “Oakdale,” an aging, grey-goateed man with painted nails and a shirt marked in Sharpie with a giant cross; “Hike-a-while,” a Spokane native who’d sold his house, given away all of his possessions, and taken to smoking pot with “militant” fervor; “Billy Goat,” who had a heart complication on the top of a 13,000-foot mountain, and was pissed off at the rangers for airlifting him out (“I wanted to die up here!” he’d reasoned).

Like these men, Colin and Casey took on their own “trail names” (monikers granted by another hiker on the trail): from early on, they became known as “Miracle Zen” and “Wabash.”

Casey (left), and Colin (second to left), with a few new friends on the summit of Mount Whitney in the Sierra Nevada (Note: Whitney is slightly off of the PCT; they took a little detour to bag the peak)

As they forged onward, they transitioned into the Northern California stretch, lush with green forests, larkspur, gooseberry, and manzanita bushes. Traversing over the Cascade Range and Lassen National Park, Colin, for the first time on the trail, faced his inner demons.

“Northern California got a little monotonous, and all the practical thoughts came rushing in,” he says. “I started thinking about getting a job, where I was going to live after the PCT, what I was doing with my life. It was an excruciating, very challenging week, full of mental struggles.”

Colin also faced the mental burden of having to film compelling footage every day. “Pulling out the camera to film yourself when you’re feeling exhausted sucks,” he adds. “There are times when you just don’t want to document the experience, but you need to — especially when you’re trying to capture the whole experience for the viewer.”

What’s more, now two months into the hike, the food began to get pretty dull, says Colin:

“We started with full-on, ridiculous junk food: candy bars and tons of cookies. That got gross pretty fast after the honeymoon period of the hike wore off, so we started transitioning to a more solid diet. I’d eat bars throughout the day. You don’t want to cook anything in the morning — you want to be efficient. You just eat bars, every hour, all day. Maybe some salami, cheese, and tortilla for lunch. And always a hearty dinner: tortellini, pasta, rice, couscous — anything that’s dehydrated and light.”

By the time Colin had crossed the border into Oregon, he’d regained his physical and mental strength.

“I started thinking less about what my friends were doing back home — that became irrelevant,” he says. “All the mattered was the present: Being in the woods was my life. Being around this vibrant community of hikers was my life. And it was a life I was in love with every day.”

Colin overlooking Mt. Hood, Oregon; Colin Arisman

The duo trekked on, past the pristine blue waters of Crater Lake, up and over the undulating peaks of Oregon’s Cascade Range, and through songbird-infested forests.

In less than a month, they had crossed the Bridge of the Gods into Washington, and faced the final 500-mile crawl to the Canadian border. Peppered with endless lakes, the land teemed with huckleberries and pine needles. It also came with a new challenge: a constant downpour of rain.

Luckily, like most of the trail, the Washington section is rife with “trail angels,” or selfless mountain town residents who take it upon themselves to provide resources for hikers. Their assistance comes in many forms, from food drops on the trail, to fly-by-night hostels and shower stations.

Resting in a small mountain town; Colin Arisman

“In one town, there was a dentist who had a ‘PCT’ banner,” says Colin. “You go in and he gives hikers free tooth care. The towns have an understanding that we have a positive impact, and they reciprocate.” Another spot, Dinsmore’s Hiker Haven, in Bearing, Washington, takes hikers in and offers hot food.

Since being established in 1968, the PCT has also changed the economic dynamics of many small mountain towns along the route, and has provided them with a pop-up tourist industry. Back in the 70s, hikers would have to send themselves food to designated spots ahead on the trail; today, general stores can be found in nearly every town, and food is readily available for re-stocking on the go. The supply has adapted to the demand.

In part, it was this generosity that kept Colin motivated to finish the trail — sometimes to an extreme. In the last push to the border, he happened through the Cascade Crest 100, an ultra-marathon in Washington’s central mountains. He ended up joining, on a whim, and hiking/running 70 miles in one day.

“I started loving to push my body,” he says.

Colin at the Canada-U.S. Border

Finally, on an overcast day in early September, Colin reached the Canadian border. He’d spent 142 days on the trail, and had traveled no less than 6 million steps to get there — yet strangely, the finish was anti-climactic:

“I was expecting that when I got to the Canadian border, something would be unlocked, there’d be this big moment of release. But there wasn’t. It was more just, ‘This is it. This is where it ends.’ I realized it was less about the fact that I got there, and more about the process it took to get there.”

Touching the wooden post of the Northern terminus symbolized the completion of a great feat, but it also signifying the bittersweet ending of an amazing journey — one that is seldom pursued.

“We all have a bucket list, things we want to do in our lives,” says Colin. “It never feels like the right time to do something scary, or something that contradicts our definition of ourself — but after having done it, you realize you don’t have to hesitate about doing these things. You can just go for stuff in life.”

***

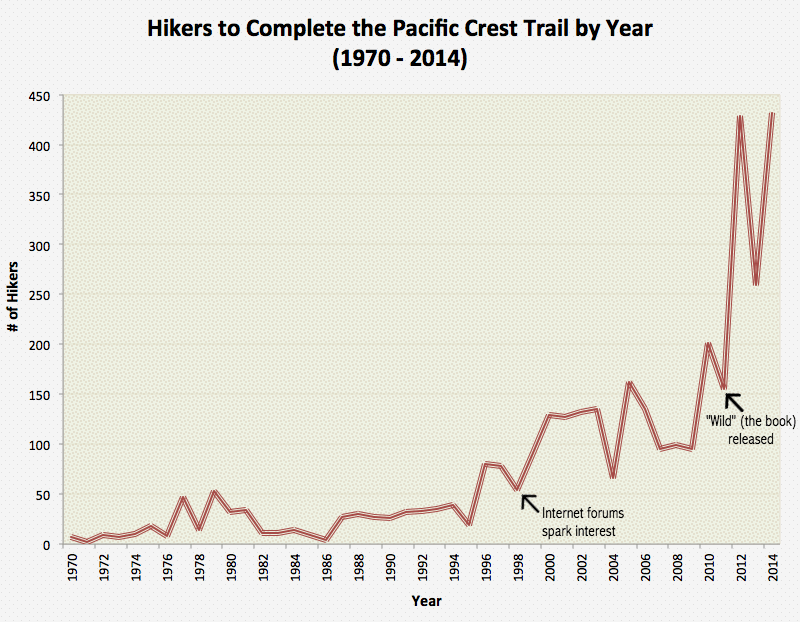

As it turns out, more people are starting to heed words like Colin’s: over the last decade, there has been a tremendous increase in the number of hikers on the Pacific Crest Trail.

Though the Pacific Crest Trail Association admits having a “lack of data” on the expansion of the trail’s use, the site does maintain a list of people who’ve completed the hike each year, dating back to 1970. We compiled these figures and graphed them:

Note: “Through hiking” refers to completing a trail from end-to-end in a single trip. Some of these data (for instance, the dip in 2013) are affected by early snowfall in Washington, which hindered completion of the trail

For the first 20 years of the PCT’s existence, less than 50 people per year completed the hike from start to finish. Then, beginning in the late 1990s, it seemed to explode in popularity.

Jack Haskel, who is the PCTA’s Trail Information Specialist (and who also through-hiked the trail himself in 2006) tells us that he suspects technology had something to do with it:

“The birth of the Internet in the late 1990s revolutionized information flow, and exposed more people to the trail. You could sit on your PC at home, research about a subject to your heart’s content, then discuss it and ask questions in online forums. These discussion sites have a way of stoking passion, and I think that passion started translating into more people taking action, and tackling the trail.”

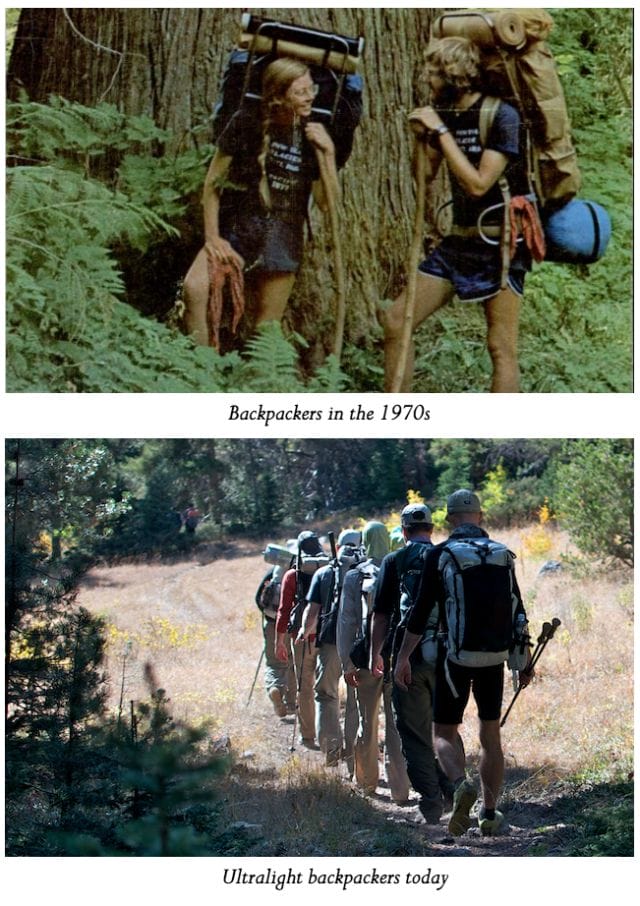

But Haskel also speculates another reason for the increase: the birth of “ultra-light” backpacking. In the mid-90s, Ray Jardin, a renowned rock climber and hiker, released Pacific Crest Trail Hikers Handbook, which proposed substituting clunky gear for incredibly lightweight, homemade alternatives.

At the time, hikers attempting long trails typically carried 60 to 70 pound backpacks, heavy tents, and metal cook-sets; Jardin’s suggestions — which included foregoing a tent for a tarp, and rouging it — revolutionized modern hikers’ approach. Since 2000, gear companies have released a number of innovations that have made hiking with a lighter pack more conceivable.

Whereas it was once a “just put on a pack and go” kind of attitude, backpacking is now divvied into several classifications, based on the “base weight” of one’s pack (that is, the pack’s weight prior to the addition of food, water, and fuel): “super-ultralight (less than 5 pounds base weight), ”“ultralight” (less than 12 pounds), and “lightweight” (less than 25 pounds). Anything more than 25 pounds is, by modern standards, considered excessively heavy.

All of these innovations, says Haskel, have made it significantly “easier to hike a lot of miles per day.”

The massive leaps in popularity around 2007 and 2012 can be more easily attributed: the 2007 film Into the Wild and Cheryl Strayed’s hugely popular 2012 book Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail both generated a tremendous amount of interest in the therapeutic effects of the hike.

The film adaptation of Wild, released in December 2014, has inspired the largest influx of hikers to ever apply for PCT permits. Last week, some 3,500 hikers were reported to have launched from the trail’s southern terminus. Gauged with previous figures — 1,870 in 2013, and 2,655 in 2014 — that’s nearly a 200% increase over two years. The film has even had an impact on the Pacific Crest Trail Association’s web traffic: “More than 15,000 people visited [our] long-distance hiking page in December 2014, writes Haskel. “That’s up 340% from last year.”

But for Colin, this data was irrelevant: the vast space of the wilderness allowed for plenty of solitude and reflection.

***

After completing his hike, Colin Arisman found himself in Oregon, using his wisdom to mentor kids through tough phases in their lives. “We brought them out to a wilderness setting, took them backpacking, and had them live in the backcountry,” he says. “Wilderness can heal.”

In the meantime, he spent hundreds of hours pouring over footage, editing, and producing Only The Essential, his short documentary film on his Pacific Crest Trail experience. (The trailer is below.)

Trailer: Only The Essential – Hiking the PCT (Colin Arisman)

Today, he’s up in rural Washington, promoting his film, and preaching the power of nature. He’s enrolled in the Wilderness Awareness School, a survival technique program aimed at advanced hikers and outdoors enthusiasts. One of his classmates, “Lorax,” happens to be a guy he met out on the trail.

“I’ve developed an inner stillness, a calmness” he says, speaking slowly. “I feel like, at any time, I can leave a comfortable situation to do something challenging.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett,who met Colin while backpacking through the Andes in Patagonia. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.