Editor’s note: The following is the personal account of Ahmed Salah, an Egyptian democracy activist.

It is adapted from his memoir, You Are Under Arrest for Masterminding the Egyptian Revolution, which he wrote with Alex Mayyasi. You can find his book on Amazon.

![]()

Each time the police entered the housing complex, my thoughts flashed back to all the times when police beat me, threatened to kill me, and told me my death would be meaningless.

I had to remind myself that I was no longer in Cairo, where Egyptian police had once arrested me on charges of “masterminding the Egyptian Revolution.” I was a refugee working for minimum wage as a desk clerk in a San Francisco housing complex. The apartment building was a single room occupancy in a tough neighborhood called the Tenderloin, and our cameras regularly filmed robberies and stabbings that the police came to investigate.

Whenever I saw the police, it reminded me of the decade I spent fighting to free Egypt, my country, from a police state. I had been a democracy activist since 2004, when I stood in downtown Cairo with 300 protesters and signs that demanded an end to corruption and the rule of Hosni Mubarak, the dictator who ruled Egypt for three decades.

For years, I led protest movements, organized demonstrations, survived a hunger strike, torture, and prison, and trained activists to lead rallies on a day of revolution. It all culminated in the best day of my life: February 11, 2011, when Hosni Mubarak resigned and Egyptians sang songs and set off fireworks in the street.

For the last three years, though, I have lived in self-imposed exile in San Francisco. I was fleeing assassination attempts and newspaper headlines that smeared me as a traitor. I found safety—and the pain of dislocation and loss.

Once I spent my days hustling between protests, interviews with journalists, and meetings with foreign diplomats. My goal was to free Egypt. Now, on any given day, I struggle to make enough money to afford a slice of pizza. My goal is to avoid homelessness.

Through it all, I have watched Egypt and the achievements of our revolution fall apart. I have watched corrupt politicians and businessmen leave prison and return to power. I have watched our elections anoint military dictators. And I have watched the police imprison and attack my friends, fellow activists, and fiancee.

The achievements of the revolution—along with the meaning and importance that once pervaded my life—often feel like sand slipping through my fingers.

***

When I was young, I thought I’d grow up to be a politician—not an activist who tries to oust them.

I was born into a politically active family. My grandfather was a member of parliament, my grandfather’s brother served as Egypt’s Minister of Defense, and my uncle helped lead a military coup against Egypt’s King Farouk and the British-backed monarchy in 1952.

Egyptians hailed the 1952 coup as liberation, but the new military government was no democracy. In 1976, my father became a politician. He dreamed of a government that helped people rather than imprisoning them.

I was only nine, but I shadowed my father his entire career. I went to party meetings, sat by his side as he met the heads of powerful families over tea, and received the world’s finest education in how dictators run a fake democracy.

My father ran for parliament three times against members of the corrupt ruling party, and he lost each time. On the eve of the first election, I was in the room when my father met with representatives of the ruling party, police officers, and my relatives who were in the military. My father had won the first round of voting. They suggested that my father would be allowed to win the election—and one day serve as Minister of Labor—if he joined the government’s political party.

When my father refused, an official promised that the election would not run smoothly. The next day, my father’s supporters complained that they saw poll workers count neatly stacked ballots, which meant that actual voters, who had to fold their ballots to fit them in ballot boxes, had not cast them. Men with guns took over polling stations, and voter turnout was over 100% because the dead voted against my father. He lost the election.

My father remained active in politics his entire life. But one evening in 1991, when I was 24-years-old and my ailing father was 64, he told me that he felt disappointed. He said he always fought for the right cause but never won. He felt that he had lost his entire life to politics, and he did not want me to make the same mistake.

He turned to me and said quietly, “Promise me that you will never enter politics.”

I did not hesitate. “I promise,” I said. “I understand.”

Two weeks later, my father died.

***

I would have lived a quiet life in Cairo as a translator and Arabic teacher—if not for the actions of George W. Bush.

I still followed Egyptian politics closely. I had grown up on the campaign trail, and I understood that politics was to blame for the deterioration of my country. When I was young, people called Cairo “Paris on the Nile,” and we had neighbors from Greece and Italy who had found opportunity in our strong economy. But by 2003, Egyptians were living in graveyards, and doctors working in public hospitals made less than $60 per month.

I wanted to take action, but I had made a promise to my father. My life changed in 2003, when the United States invaded Iraq.

As the drums of war sounded in America, Egyptians believed that we could not accept a foreign invasion of another Arab country. We were furious that our government, which was allied with the United States, allowed American and British warships to sail through the Suez Canal toward Iraq. I had an intuition that if the United States attacked Iraq, Egyptians would take to the streets.

On March 20, 2003, America began bombing Baghdad. Acting on my hunch, I went to Tahrir Square, a central point in downtown Cairo. I arrived to an incredible scene.

Several thousand protesters occupied the square. They had erected makeshift barricades that blocked traffic from the intersection, and I did not see any police.

I stayed in Tahrir all afternoon. Protesters wrote slogans on the asphalt, sang and chanted in circles, and held discussions. By sunset, tens of thousands of Egyptians filled the square.The next day, we occupied Tahrir again. For the first time in my life, I felt free.

It did not last long. Riot police attacked us as we attempted to march out of the square. I escaped unharmed, but I saw bodies of bleeding, unconscious protesters piled like bales of hay. Policemen in and out of uniform snatched protesters and beat them. Once protesters fell to the ground, policemen tied their arms with their own clothes and dragged them to the nearest pile.

The attack delivered a clear message: Don’t speak up; don’t challenge the government. But we did not listen.

A year and a half later, I stood with 300 protesters on the steps of Cairo’s High Court. We held signs that read “Enough corruption!” and “Enough tyranny!” We represented a new protest movement called the Egyptian Movement for Change, which was founded by prominent businessmen, academics, and politicians at a series of meetings prompted by the brutal end of the Iraq War protests. We nicknamed it “Kefaya,” which means “Enough,” because we’d had enough of our corrupt leaders.

Policemen surrounded our protest, but they did not attack. The demonstration would have been boring if it weren’t revolutionary. It was the first protest calling for an Egyptian president’s resignation since 1977. I felt as much adrenaline as a boxer in the ring.

From then on, I was hooked on activism. Kefaya was Egypt’s first protest movement, and it offered a way to address Egyptian politics without joining a political party.

I had finally found a way to fight for my father’s ideals without breaking the promise I made him.

***

An activist’s life can feel like the definition of insanity: doing the same things over and over and expecting a different result.

From 2005 to 2012, I was a full time activist. I only worked as an Arabic teacher enough to pay my bills. This allowed me to play a leading role in three of Egypt’s most important protest movements: I became one of seven members of Kefaya’s governing body; I was elected the head coordinator of Youth for Change, a movement of young activists allied with Kefaya; and in 2008, I co-founded the April 6th Movement with an engineer named Ahmed Maher.

Failure followed our every success.

In 2006, Youth for Change and our allies occupied several blocks in the heart of Cairo. Nearby, Egypt’s judges held a sit-in to demand democratic reforms. We called the area “liberated territory,” and we painted graffiti with slogans like “This is the tomb of Mubarak.”

I remember telling a friend, “This is historic!” We felt sure that we would soon force President Mubarak to resign and call for new elections.

Then the police attacked our encampment and arrested me and eleven activists. I spent six weeks in prison, indefinitely detained and on hunger strike. Guards beat me, held mock executions, and told me my death would just be a bit of paperwork. Before the guards released me, the head of State Security threatened to bury me in prison if I showed my face at a protest again.

But in 2008, democratic change once again seemed attainable. Egyptians who worked at state-owned factories had organized strikes all over the country. Their demands started to turn political, and on April 6, 2008, activists organized a nationwide strike in solidarity with them.

It was a success, and reporters, who gushed over activists’ use of Facebook groups to publicize the strike, coined a new term: a Twitter Revolution. Ahmed Maher, a former member of Youth for Change, co-created the largest of these Facebook groups. After the strike, I worked with him to turn it into a new protest group, the April 6th Youth Movement.

Yet plans for our next national strike floundered, and while the April 6th Movement kept the media talking about activism and political change, we never created a mass movement.

Over and over, I saw our push for democracy gain momentum only to putter out.

Activists and political dissidents gathered over 1 million signatures for a petition that demanded democratic reforms. The government ignored it.

We organized protests in response to fraudulent elections, a church bombing, and the murder of an innocent, young Egyptian by the police. Each protestfelt powerful, but did not lead to sustained protests or the growth of our movement.

But that is the life of an activist.

The role of an activist is not to lead the masses with a flag draped around his or her shoulders. Activists meet a few people at a time in a coffee shop to explain in hushed tones why they should believe when no one else does.

An activist’s moment is not the moment of change; it is the period when change seems impossible.

***

This is what makes activism so difficult. Activists are idealists in a cynics’ world: they preach nonviolence while taking on a government with tanks, secret prisons, and limitless resources.

At times my work felt important and respected, which motivated me. I negotiated agreements between activists and political groups like the Muslim Brotherhood. I organized large protests and debated government hacks on satellite television. I met with ambassadors, members of Congress, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

One of these meetings became infamous when Wikileaks published the American Ambassador to Egypt’s report on our meeting. “[The April 6th Movement’s] stated goal of replacing the current regime with a parliamentary democracy prior to the 2011 presidential elections,” she wrote, “is highly unrealistic.”

But for every day I spent telling reporters about our demands for real elections while marching with thousands of Egyptians, I spent weeks mediating petty disputes among activists and crossing Cairo for a protest that only ten people attended.

Even basic questions—like how to communicate with members of Youth for Change and April 6th—proved vexing: Only the richest Egyptians checked the Internet every day or could afford to send group text messages.

Despite my righteous cause, I also could not escape the ugliness of politics that my father had warned me about. Activists jealously fought over leadership positions, and when I had a falling out with my April 6th co-founder Ahmed Maher, he told reporters that I was never part of the movement.

Two things kept me going through all the setbacks, danger, and ugliness.

The first was the influence of my father. Whenever I grew frustrated, I remembered his perseverance through decades of adversity.

The second was my fiancee: Mahitab El Gilani. We met in 2005, and we got engaged a year later.

We are still unmarried. My activism served as a scarlet letter when I tried to work, making it difficult to attain the financial stability expected by our families. But the bigger problem was the danger of activism. We got engaged just after my release from prison—around the time I stopped talking to my brother because Egypt’s government often silences dissidents by jailing or torturing their family.

Another fiancee might have demanded that I choose between her and activism, but Mahitab was even more committed than me.

We met at her first protest, and she became an activist. She had the perfect personality for it. Mahitab speaks with the intensity of a firecracker that never dies out. Whenever you think she must be out of breath, she launches into another flurry of arguments. During a signature-gathering campaign in 2010, she directed a team of canvassers and—for several months—spent all day going door-to-door.

Whenever my enthusiasm flagged, Mahitab convinced me to keep trying.

Still, when activists began sharing a call for revolution in 2011, I doubted we could succeed.

***

Egyptian activists dared to talk about revolution because we had just witnessed one: on January 14, 2011, the President of Tunisia, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, had fled his country.

Ben Ali was a dictator whose 22-year rule in Tunisia had resembled Mubarak’s in Egypt. But in December 2010, a fruit vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi had set himself on fire after the police asked him to pay a bribe. In just 28 days, protests by his family escalated into national protests that forced the Tunisian president from power.

Egyptians watched the Tunisian Revolution live from our living rooms. It destroyed the sense of inevitability that had propped up Arab dictators, and almost immediately, Egyptian activists started sharing a blog post that called for a similar revolution in Egypt on January 25, 2011.

The next day, I met with eighty activists to come up with a plan.

Our emotions ran raw. We represented different political parties and protest groups, and many of us had spent a decade protesting and attending meetings like these. We felt like a band that keeps flirting with fame, but will break up if the next album is not a hit.

By 2011, the way we prepared for large protests had become habitual. We’d choose a time, a place, and perhaps a theme or theatrics—like placing tape over our mouths to symbolize censorship. Then we’d spread the word by mobilizing our network of activists, talking to independent newspapers, posting updates online, handing out flyers, and painting graffiti.

The problem was that we did not have enough people. We’d always imagined months of successful demonstrations growing our movement until we could mobilize tens of thousands of Egyptians. But the previous year had not been successful, and many activists had abandoned politics. We left the meeting frustrated, having agreed on nothing except the fact that we did not have enough activists to stage a large protest.

We barely mentioned Facebook or Twitter. This may surprise readers who heard the media describe Egypt’s revolution as a “Facebook Revolution”—a spontaneous uprising organized by young people on social media.

But you can’t organize a revolution online—at least not in Egypt.

***

I have always loved technology, and for a time, I believed the Internet was a powerful tool for dissidents.

In 2006, I hosted a podcast, which evaded government censorship of radio shows, where I interviewed politicians and activists. In 2008, the growth of the April 6th Facebook group, which promoted a national strike, so impressed me that I teamed up with its creator to found a youth protest movement from its members.

Our use of social media was an incredibly effective media strategy. It allowed journalists to cover our protests from their desks, and Western journalists, who loved the idea of tech-savvy protesters taking down dictators with a tweet, wrote feature stories on our April 6th Youth Movement.

While the press glorified us as “Facebook activists”, though, we were learning that the Internet was a poor tool for recruiting activists and organizing protests in Egypt.

Our April 6th Facebook group had over 70,000 members, but the gap between venting on Facebook and braving the streets seemed to be a chasm. My co-founder and I only managed to recruit roughly two dozen of them to join our protest group. Despite all our efforts to announce, plan, and promote protests on the Facebook page, our digital supporters never joined us in the streets.

The man most credited by Western press with using the Internet to spark Egypt’s revolution is Wael Ghonim, a Google marketing executive. Wael Ghonim had created a viral Facebook group called “We Are All Khaled Said” to publicize the murder of a young Egyptian by the police. Ghonim used the group to organize what he called “humanitarian stands”—events where we silently stood holding Bibles and Korans in solidarity with victims of police brutality. In 2011, Ghonim used the Facebook group to promote the protests that sparked the Egyptian Revolution.

I understand why outsiders attributed the revolution to people like Ghonim. Facebook posts are more visible than secret meetings, and Egyptians who spoke English and appeared on CNN had smartphones.

But the idea that activists organized the revolution on Facebook is silly. I’ve seen statistics that say 25% of Egyptians had Internet access in 2011 and others that say only 10% had used the Internet at least once. What I know is that I could not count on activists to check their email even once a week.

I also experienced the failures of Facebook Revolutions during each of our previous protests. Even the most successful of Ghonim’s events, which did not call for political change, were attended by only a few thousand Egyptians—despite tens of thousands of people RSVPing on Facebook. Ghonim himself has said that the Internet could not reach Egypt’s working class—and that he left the planning of the January 25 protests and rallies to street activists.

The transparency of the Internet is a double-edged sword. It’s effective at reaching journalists and a mass of people. But organizing protests online is like faxing the Head of Police your plans.

And as I discovered a week before January 25, the day of our planned revolution, we needed a new plan.

***

After my discouraging meeting with democracy activists, I decided to take a new tack in figuring out how to get Egyptians to take to the streets: I asked them about it.

Posing as a journalist, I spent hours interviewing Egyptians. I started by asking them if they planned to protest on January 25. “What protests?” they responded.

I felt better when I asked their opinion of Hosni Mubarak. Some echoed state propaganda about “our strong and wise president.” But many of them agreed with me. “This is the most corrupt government in our history!” one young woman fumed.

With these people, I dropped my objective journalist voice and revealed myself as an activist planning protests. “Will you join us?” I asked. They said “no” and looked at me like I was a fool. But what stuck with me is how many of them said they would brave the streets—in certain conditions.

“If it’s the day of the revolution and the real thing, I will face anything!” one man told me. Another Egyptian said, “I’ll go out in the street when I see everyone else out there. But I won’t be the stupid fool who goes first!”

I felt frustrated as I walked home. People wanted Mubarak gone. Yet even after seeing Tunisia’s example, they did not think protests could topple him. They would take action, but only after everyone else did first. How could we resolve this riddle?

The next day, I had a plan—one I conceived with the help of other dissidents. We would not announce one gathering point for a protest. If we assembled in a major square, we’d look like a small group (like “stupid fools,” as the man I interviewed put it), and the police could wait there to arrest us.

Instead we would recruit people to plan and lead rallies in every neighborhood. In the narrow confines of side streets, the protests would seem huge and convince Egyptians that the day of revolution was at hand. As more protesters joined, they’d advance from alleyways to boulevards to downtown. These rallies would be like springs and streams feeding into a raging river. By the time we converged in Tahrir Square, we might be powerful enough to break the dam of riot police.

When I shared my ideas with Mahitab and a core group of activists, they responded with enthusiasm. Drawing on the network of activists we’d built up over 10 years of protests, we explained the plan and asked everyone to share it and find more volunteers who could organize rallies.

I spent every hour training people to follow this plan on January 25. Members of protest movements I had led—Kefaya, Youth for Change, and April 6th—connected me with activists and people engaged in politics in Cairo, Alexandria, and Suez. Mahitab also found potential recruits in the thousands of forms she had from people who had signed political petitions. (The forms included contact information.)

I spoke over and over to volunteers in coffee shops until I spoke like a tape recorder. Mahitab only had to assemble a room of people and press play, and I would talk revolution and explain how to plan and lead a rally on January 25.

I tried to hide the fact that I did not know if we would succeed.

***

January 25 exceeded my wildest expectations.

By the time I woke after a fitful night of sleep, a rally was already underway in my neighborhood of Shubra. As I rushed to join it, I answered phone calls from activists who told me about rallying in the streets and facing off with cops all over the country.

When I found the closest rally, the street was packed with thousands of protesters. I looked around in amazement. I had been an activist for eight years, yet the streets were full of men and women I had never seen, and they were leading chants! As I lifted my voice to join them, I thought to myself: My God! Where have you been? We’ve been waiting for you!

As we’d planned, we walked through Cairo’s neighborhoods for hours, encouraging surprised onlookers to join us. By the time we braved the main streets, we filled them. And by the time we approached Tahrir Square, we had the numbers to confront the police.

People joining our rally told us that police had blocked the nearby 6th of October Bridge, which spans the Nile. We heard them fighting to keep protesters, whose rallies began in neighborhoods across the river, from crossing.

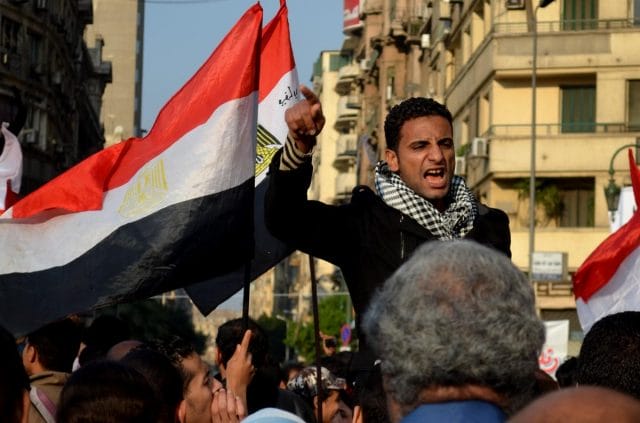

A picture taken by Ahmed Salah in Tahrir Square in January 2011

When we entered Tahrir Square, we entered a battlefield. Tear gas clouded the square, and I could make out the hazy forms of protesters and a dark tide of police opposite them.

Few of the people around me had attended a protest before, let alone clashed with police, and yet, with a yell, they charged forward. Spreading out into the open space, they sprinted fifty yards to the frontlines and dodged the stones and teargas canisters raining down.

I believe in nonviolent activism, and I oppose tactics like destroying government buildings or killing government forces. Yet I do not advocate meekly bearing the blows from the regime’s thugs. We knew we had to defend ourselves.

For two hours, we threw rocks at the police and surged forward against their batons, tear gas, and water cannons. More rallies arrived, and we pushed the police back until they retreated out of the square.

We celebrated and looked at each other in amazement. Had we really defeated the feared police state?

***

Readers who follow Middle Eastern politics may be surprised by my assertion that our plan of recruiting people in person and rallying in side streets—and not the Internet—was the key to our success.

I can understand why. We kept these plans secret, while journalists could easily find Facebook groups.

But the signs are there if you look for them. On January 25, protesters did not head straight to Tahrir Square. Instead they formed dozens of rallies in different neighborhoods—rallies that Wael Ghonim recommended (via his Facebook group) that people search out after he spoke with street activists.

Our plan did eventually leak, and on January 27, The Atlantic published a guide made by street activists. The guide warns Egyptians to “Distribute [the plan] through email printing and photocopies only!” because “Twitter and Facebook are being monitored.”

By following this plan, we solved the chicken and egg problem of people only wanting to join protests if they seemed large. Each rally recruited thousands of Egyptians who together defeated the police and occupied central squares in Cairo, Alexandria, Mahalla, and other cities.

We had the world’s attention, and the word revolution no longer seemed crazy. But success was not assured.

The night of January 25, riot police attacked, drove us from the square, and arrested me along with thousands of protesters. I was released three days later, and during my first hours back in the square, I escaped death only because a heroic stranger pulled me away from sniper fire.

On February 2, we fought thousands of thugs paid by members of the government to drive us out of Tahrir. The attack felt surreal—dozens of the attackers charged the square mounted on camels that tourists usually pay to ride at the Giza pyramids. During our two-day defense of the square, we developed a system of tapping rocks on lightposts to call for reinforcements and adopted specific roles. I have poor health, so I focused on breaking up rubble into ammunition for stronger protesters to throw.

We spent two dangerous weeks in the square, and I loved every minute of it.

Tahrir felt like a utopia. Businessmen talked with beggars. Women in designer clothes picked up garbage. People shared sandwiches with strangers and left their cell phones to charge unguarded. When Muslims gathered to pray, Coptic Christians surrounded and protected them. When the square was attacked, we ran toward the danger to help. Everyone was equal and generous and brave.

It was beautiful. It is hard to describe, but the energy in Tahrir felt like the opposite of mob rule. Everyone in Tahrir knew tanks could roll in and kill us. We were prepared to die for a cause, so why would we argue or act dishonestly or be anything other than the best we could be?

I hope everyone gets the chance to one day feel the way we did on February 11, 2011, when President Hosni Mubarak stepped down and we lit fireworks and sang songs and painted every wall near Tahrir in the colors of the Egyptian flag.

***

Ten years after I became an activist, we finally had our revolution.

But it was not complete. Toppling President Mubarak was just the tip of the iceberg.

When Mubarak resigned, he ceded his authority to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), a group of roughly 20 generals that convened only during times of war or national emergency. They quickly suspended the Constitution and dissolved the parliament, which meant that a secretive group of generals would lead our “democratic transition” by decree.

These generals were not interested in change; they were the corrupt system.

Each of Egypt’s presidents had come from the military and given military officers enormous privileges. Once the generals of the SCAF assumed power, the same police that beat us before the revolution harassed us when we protested the military. Dissidents were imprisoned under the same restrictive laws. The same corrupt businessmen bought elections.

We kept protesting to demand the generals turn power over to civilians, but we faced worse repression than ever. The state-owned media called us rioters and troublemakers even as riot police killed hundreds of protesters.

Graffiti near Tahrir Square in 2012

Due to my leadership role—especially my role talking to American diplomats and officials, which Wikileaks publicly revealed in 2011—I was a central target of both state security and the media. Prominent newspaper articles smeared me as a traitor paid by the CIA to undermine Egypt. Talk show hosts—who were Egypt’s version of Rush Limbaugh—said I should be charged with treason.

One quiet night in Tahrir, I barely escaped an assassination attempt. A group of men in plain clothes choked me, carried me to a dark alley outside the square, and pulled out knives. I only survived because my fiancee Mahitab rallied a group of activists to come make noise and wrestle me away from the attackers.

Not every activist was so lucky. A friend of mine, Mohamed al Masry, received phone calls from police officers who warned him against associating with me. He was an open-minded man who spoke several languages, and we found his body one day in downtown Cairo. He had stab wounds like the ones intended for me.

In the year after we ousted Mubarak, I slowly accepted that I needed to leave Egypt. I had an American visa since I had gone to D.C. to meet with politicians, so I decided to fly to Washington. My hope was that activists and liberals would succeed in reforming Egypt, and that I could return home soon.

***

My last day in Egypt was January 25, 2012. I spent it in Tahrir Square with Mahitab, celebrating the anniversary of the revolution. We nearly missed our flight because I spent so much time taking photographs of clever protest signs, babies with face paint, and huge Egyptian flags with the words “January 25 Revolution” emblazoned on them.

When Mahitab and I arrived in Washington D.C., we were greeted like heroes or foreign dignitaries. My Egyptian friends who worked on Middle East policy hosted us in their homes and shepherded me between meetings with journalists, State Department officials, and members of Congress. By then I was a regular in the Congressional cafeteria. I bought a coffee and the cheapest slice of pizza each time.

Mahitab and I gave talks about the revolution at a dozen universities and Occupy Wall Street encampments. We enjoyed meeting supportive people—they praised and congratulated us so much that we became embarrassed. We tried to make it clear that Egypt was not yet free.

Each night, I stayed up until 5 a.m. to Skype with activists. We’d discuss politics and plan protests, media campaigns, and events about political reforms.

Although I had fled my country, I felt like a proud Egyptian fighting for its liberation.

But as weeks turned into months, the weight of thousands of hours away from my home and my cause settled on me. I was waiting for conditions in Egypt to improve, but they did not. In Egypt’s first real presidential election, three liberal candidates split the votes of Egypt’s democrats. The liberals lost, and the Muslim Brotherhood candidate narrowly defeated a member of the military. Mahitab returned to Cairo without me; it was a hard, uncertain goodbye.

The election represented Egyptian politics since the revolution: a power struggle between military dictators and religious fanatics. And the Muslim Brotherhood—whose religiosity, I believe, is a trojan horse for pure political ambition—treated activists just as harshly as the military. The government and media kept calling me a traitor. During my Skype calls, I increasingly heard about arrests, travel bans, and deaths.

Three months after the election, in September 2012, I called Mahitab to wish her a happy birthday. She shyly told me she’d received some medical attention after a protest. When I pressed for details, she explained that riot police had attacked the protesters, chased Mahitab to the bank of the Nile, and punched and kicked her while she lay on the ground. She had lost sight in her right eye. I was speechless. It was terrible.

I felt helpless, and I wanted to see Mahitab. But I knew I could not. Realizing that my exile from Egypt would probably be permanent, I applied for political asylum.

This meant I had to face the reality that my money was running out, and I could not legally work until I received asylum. On occasion, I made money teaching Arabic to someone I found on Craigslist. But even though I ate cheaply and, since I’d overstayed my welcome in friends’ homes, moved into a cheap room in the basement of a house in Virginia, I stressed about money.

My wait for legal status was worse because I’d lost my sense of purpose. Since I had left Egypt months ago, journalists rarely sought my perspective, and politicians and officials politely turned down my requests for meetings. Members of Congress had told me previously that my asylum application would be accepted in 40 days because I had risked my life to address Congress in 2009. Instead it took a year.

I was old news.

***

I felt frustrated and unfocused. I lived for my occasional, late-night Skype calls with activists. Otherwise I stayed in my room—the bus from Virginia to D.C. cost as much as I spent on food each day. In the stuffy basement, I spent hours reading and sharing political news on Facebook. Often I played computer games just to keep my mind occupied.

The news I read was grim. The Muslim Brotherhood government was seeking power in ways that made us fear our country would soon look like an Iranian theocracy. At one point, the president issued a decree that placed his actions beyond the review of any Egyptian court, which gave him nearly absolute power. Protests led by Mahitab and others weremet with violent opposition.

After several months of purgatory, I bought a plane ticket to San Francisco. Egyptian newspapers kept calling me a “CIA agent,” and I did not want to hand them ammunition by living in Washington. I chose San Francisco because I knew it was a hub for activists—and I thought I would face fewer racist comments about Arabs and Muslims in California.

When I tried to justify the expense, I imagined that in San Francisco I could build a new life by befriending American activists and tutoring people in Arabic. My friends in Occupy Wall Street had even introduced me to a member of the San Francisco movement who offered to host me in his apartment.

But when I arrived, I struggled to find the energy to search Craigslist and ask friends if they knew of an opportunity. I felt burdened with something dark and deep. Motivation seemed like a childhood memory, and when I did teach an Arabic lesson or meet a friend or journalist, leaving the house felt like the mental equivalent of climbing ten flights of stairs.

Eventually I visited a clinic where a doctor diagnosed me with post traumatic stress disorder. He compared my condition to a soldier returning from war. During the struggle, my mind kept functioning through my time in prison, the protests turned street battles, and the assassination attempt. But once I left Egypt, my mind became overwhelmed by the brutality.

Ahmed (second from left) in Tahrir Square with Mahitab and friends

While I focused on my treatment, Egyptians suffered even more. In June 2013, 10 million Egyptians took to the streets to demand the resignation of Mohamed Morsi, the member of the Muslim Brotherhood serving as president. There were even more protesters than had opposed Mubarak, and as civil war began to look plausible, the military arrested Morsi and took control of the government.

Egyptians cheered the removal of another autocratic ruler, and I cautiously joined them, offering my congratulations to Mahitab and others over Skype. But our celebration did not last long. When the Muslim Brotherhood occupied major squares in protest, the military massacred them. Soldiers bulldozed through the encampments and shot live ammunition from helicopters. Journalists described people sprinting with bodies in their arms, and Human Rights Watch estimated the death toll at over 1,000 unarmed men, women, and children.

After the massacre, I no longer stayed up late to Skype with activists. Protest was nearly impossible; the government regularly shot or “disappeared” anyone who denounced it. I gave up any hope of returning home and watched the revolution come undone.

Egypt’s top general, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, ran for president and won 96% of the vote. Every newspaper backed Sisi and called him a hero. Businesses bought billboards to support his candidacy. Sisi’s victory was so assured that he and the government focused on inflating voter turnout figures. But few Egyptians voted.

Our new military government undid other achievements of the revolution. In 2011, I had jumped up and down in front of the television as I saw Mubarak, his sons, and corrupt members of his government put on trial. In 2014 and 2015, I sat paralyzed as I read that judges had dismissed their charges, which allowed them to return to politics.

Egypt was like a parody of a dictatorship. Soldiers appeared on college campuses to confront students who criticized the government. The state executed an activist I knew on charges of committing a crime that took place after he’d been arrested. Liberal politicians fled the country, as did Bassem Youssef, a brilliant satirist who had a TV show that resembled Jon Stewart’s Daily Show.

The achievements of the revolution felt like sand slipping through my fingers.

***

My friends often ask me what I will do now that I can’t return to Egypt.

The truth is that I don’t know. I am lost, and the only reason that I am not homeless is that generous friends in San Francisco have opened their homes to me.

It makes me feel depressed and small to admit this after years of confidently sharing my plans with activists, journalists, politicians, and ambassadors. But my poverty and health problems make long-term planning impossible. My ambitions are more modest now than they were when I promised Egyptians that we could free our country: I want to pay off my credit card debt and rent my own room.

This has not been easy. My asylum application was eventually accepted, and a year ago, I found a job. It was a tough one. I worked as a desk clerk in a single room occupancy in the Tenderloin. The job paid minimum wage. During my shifts, the police frequently arrived to look at our security cameras, which filmed multiple stabbings and burglaries. One day a man entered the building, pointed at me through the glass, and made a throat-cutting gesture.

The job reminded me of home in the worst possible way. I thought back to the dead bodies in Tahrir and the men pulling out knives the night Mahitab saved me from assassination. The job intensified the anxiety and depression of my PTSD until I quit.

I haven’t found another job since. My poor health makes it a challenge just to get out of bed in the morning.

I have now lived in San Francisco for over three years, and really I can’t complain. I have a place to live, and while I am in debt, I’ve managed to make enough money from teaching Arabic to keep going. I like this city and the fact that I can go to the ocean, even though it fills me with survivor’s guilt. I do not know why I should live free while brave Egyptians suffer.

At least that is what I tell myself when I feel magnanimous. But I can’t help feeling bitter that I lost everything. I worked hard and suffered for Egypt, and I was forced to flee and watch as the government destroyed my reputation. I feel proud that I played an important role in history, but also forgotten by the people who once praised me and the journalists and historians who chronicled the revolution.

I know there is nothing personal about what happened to me. The forces that left me forgotten in exile are the ones my father warned me about: the cruel machinery of politics and greed and interests.

Every now and then, I think of my father, and of all the men and women like me. The people who fought hard for freedom and nearly changed history like Gandhi or Nelson Mandela, but whose efforts ultimately fell short. There must be a lot of us who played a role in history but became footnotes.

I wish the history books followed them a little longer, and paid them a bit more attention. I’d like to know how their stories end. I’d like to know if they found happiness.

![]()

Ahmed Salah’s memoir “You Are Under Arrest for Masterminding the Egyptian Revolution” is available on Amazon.

You can get in touch with Ahmed and his co-author Alex Mayyasi by contacting Alex.