Photo credit: JR P

The image of Marilyn Monroe holding down her dress as a subway train passes adorns countless posters — and inspired this hideous sculpture. Less well known is the fact that the iconic image also played a role in framing how Americans think about marriage.

The scene comes from the 1955 film The Seven Year Itch about a man struggling with his attraction to his young neighbor (played by Monroe) while his wife and son are on vacation. At the time, the phrase “7 year itch” referred to getting bored with anything — often a job — after a long period of time. In the film, the protagonist’s disloyal thoughts begin when he reads a book by a psychiatrist who claims that most men cheat on their wives in the seventh year of marriage.

Although Hollywood is known to exaggerate, some actual data does support the idea. Psychologists took up the term to describe findings that divorce rates seem to spike around 4 to 7 years into a marriage, and academics, journalists, and marriage experts continue to use the term today.

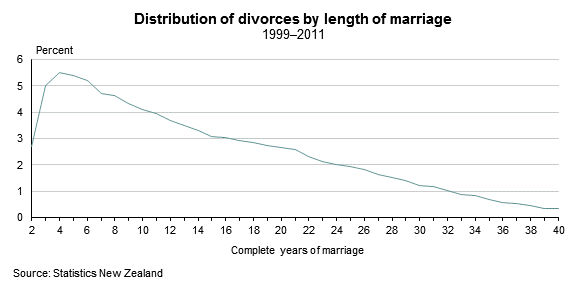

Since the United States doesn’t collect the most granular data on divorce rates, some of the best illustrations of the 7 year itch come from other countries. This data from New Zealand shows the spike quite clearly:

American census data shows a similar pattern. Among men married in the early to mid 1960s, 11.2% divorced after 5-10 years of marriage while only 2% divorced after 35 to 40 years of marriage. Marriage data is inevitably backward looking, but among men married in the early to mid 1990s, we similarly see that 12.4% divorced after 5-10 years of marriage.

Divorce rates are a blunt instrument for understanding the durability or “success” of marriages, so there is a lot to squabble about. Some psychologists and demographers point out that since divorces peak at around 7 years of marriage, that means the “itch” must come earlier, given that people take time between first thinking about infidelity or divorce and actually acting on it. Others contest whether the itch comes sooner, perhaps after 3 or 4 years, and debate potential causes that range from childcare siphoning all the energy from marriages to 7 years representing enough time for men and women to change significantly.

But drawing from studies that find happiness levels in couples declining after a short “honeymoon period” for around 5-10 years before stabilizing, the 7 year itch idea has stuck. It fits into general pessimism about the durability of marriages and the narrative of increasing divorce rates. With some half of marriages ending in divorce and the median divorce taking place after 7 years, “Till death do us part” doesn’t sound very accurate. A European politician with 2 divorces under his belt has cited the idea to propose that marriage last only 7 years. “This would mean that one will only commit for a fixed period,” he told reporters, “and will actively have to renew your vows if you still want to continue.”

While divorce rates do reflect the pattern of the 7 year itch, the effect is not nearly strong enough to back up popular conceptions of everyone’s marriages ending within a few years. Graphs like the one above show a spike in divorce rates, but that spike is only a difference of a few percentage points. Couples 7 years into a marriage only divorce at rates 2% higher than those 15 years into matrimony.

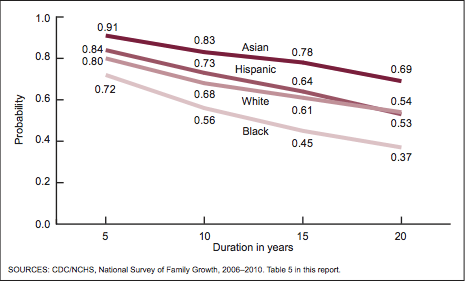

When we look at a different representation of divorce rates, marriages look much more durable:

Probability of 1st Marriage Remaining Intact Among American Women

Source: 2012 National Health Statistics Report, CDC. Applicable to women ages 15-44.

The fact that over 10% of American marriages end within 5 years — and that only about half last “until death” — does not speak well of an institution meant to be permanent. But the data does not support the popular image of marriage lasting only a few years. Divorce rates are higher in the first 5 or so years, but at a rate you might expect. It’s hardly an epidemic.

The spike in divorces after 5-7 years of marriage is also trumped by many other factors. One study using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that among couples who did not complete high school, half of all marriages ended in divorce. In contrast, the divorce rate among college graduate couples was 30%. This widely found result is not destiny. Rather it reflects that college graduates tend to marry later and have higher incomes, whereas poverty and getting married young both have been found to increase the risk of divorce.

Divorce rates only tell us so much about whether people are fulfilled by their marriages. Does the increasing rate of divorce from the 1960s to 2000 mean that Americans found less happiness in marriage? Or did no-fault divorce and changing norms allow people to escape unhappy marriages?

But even by the crude instrument of divorce rates, pessimism about matrimony appears overblown. The latest US census data shows that among marriages that began in the late nineties, the percentage that lasted at least 5 years is the highest it has been since Lyndon Johnson served as president. Reports of the demise of marriage have been greatly exaggerated.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.