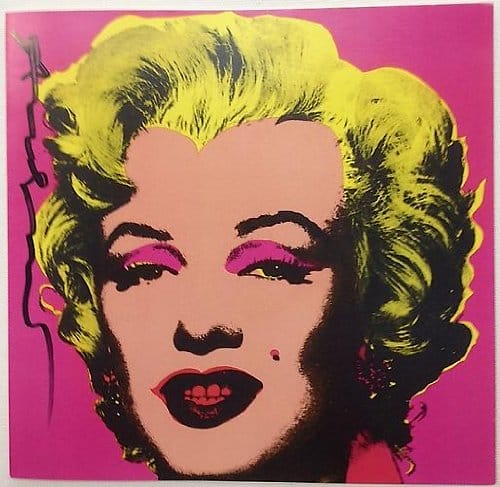

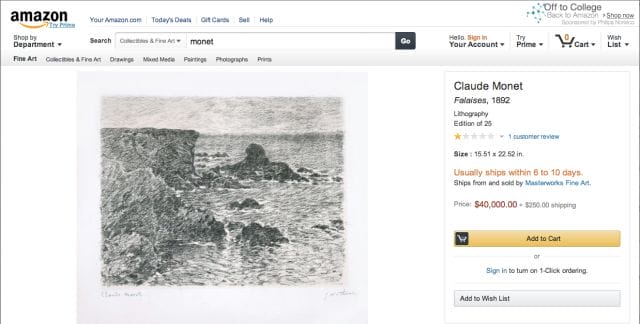

From its roots as an online bookseller, Amazon.com has expanded into selling movies, toys, furniture, and just about everything. Recently it added fine art, so instead of traveling to a Manhattan art gallery, you can now spend tens of thousands of dollars on a Monet or Warhol without getting off the couch. Reuters notes of the move:

On Tuesday [August 6], Amazon.com launched Amazon Art, a section of the site that boasts 40,000 works of art from 4,500 artists represented by 150 dealers.

With price points below $100 and up to more than $4 million (but the majority of works priced between $1000 and $10,000), Amazon is solidly placing itself in the realm of startups like Artsy, Artspace, and Paddle8, in inventory if not in aesthetics or art world pretension.

Amazon Art’s critical reception could be summed up as “puzzling.” Commentators have generally pointed out that the site does not appear to be tailored to the fine art world (for example, one gallery owner notes that searching by size, color, or orientation is not how galleries and collectors look for art), questioned whether authenticity would be a problem, and doubted the utility of applying Amazon’s strengths of low cost and convenience to a world that thrives on high price tags and exclusivity.

Economist Tyler Cowen writes that he does “not think that it will revolutionize the art world”:

I expect the real business here to come in posters, lower quality lithographs, and screen prints, not fine art per se. And sold on a commodity basis. There is nothing wrong with that, but I don’t think it will amount to much more aesthetic importance than say Amazon selling tennis balls or lawnmowers.

Matt Yglesias of Slate suggests that “there’s a real business opportunity,” but he believes it is “in the four-to-five-figure range selling stuff that art snobs would look down on to people whom art snobs would look down on.”

While Jeff Bezos may force us to eat our hats, Priceonomics would like to suggest a key problem for Amazon Art. The experience of buying a product – when it is a book or pack of diapers – is often an inconvenience that people will gladly use Amazon to avoid. But in the case of fine art, that experience is something of value – a key part of the product and inherently necessary to pricing the product.

To understand why, we would point to the experience of a young entrepreneur named James Maskell in a similar market – that of fine wine.

While not identical, art and wine have similar dynamics. The majority of the wine market consists of bottles that sell under $10, but at the high end, bottles sell for thousands of dollars. Fine wine is both a luxury product and, due to the fact that wines get better and more valuable with age, an investment opportunity. Both oenophiles and professional traders literally buy and sell wine in an attempt to arbitrage the wine market.

Fine wine and art appear to be impossible to price due to their subjective value. Just as a preserved shark in a tank selling as a piece of art called “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living” for millions of dollars baffles people outside the art world, spending $20,000 for a case of wine baffles those of us who consider a $50 bottle a huge splurge.

Priceonomics spoke with Maskell several months ago for an article on the price of wine. In 2011, Maskell founded Vinetrade, a marketplace for buying and selling fine wine. Maskell saw an opportunity to cut out the many middlemen who increased the price of wine, bring technology to the labor intensive world of wine storage, and increase price transparency. With Vinetrade, he writes,

We were playing a classic disintermediation game – connect buyers and sellers, increase transparency, cut margins, and take a small cut for ourselves.

In other words, Maskell was implementing the Amazon experience. But in early 2013, Maskell and his co-founder decided to shut Vinetrade down, believing that it could not be a scaleable business. As we previously wrote:

The most fundamental problem, as they discovered, was that people resisted ordering wine online. For hobbyists, it destroyed the fun of being part of an elite group that unashamedly used words like “tannin” and “subtle.” For investors, it denied them the opportunity to exchange information with salesmen.

“Even if they don’t admit it,” James told us, “people like having the posh voice on the other end of the line. They want reassurance and they want to feel part of the ‘boy’s club.’”

In the stock market, most assets have an underlying value based on objective facts. In wine, taste and quality is a factor of perception. Investors deal, then, in perceptions of perceptions. In the small world of insanely expensive wine, value and prices are determined by what the wine clique is saying about a given vintage.

There are real differences in the production of wine, but the value of fine wine is mostly a social construct. As we’ve written before, the correlation between price and the average person’s enjoyment of a wine is almost zero. Even people educated about wine can be tricked into believing that a white wine is a red wine or declaring a $5 bottle an extraordinary vintage. Our sense of taste is simply so easily tricked and warped by perception that taste plays a small role in the price of wine (when it costs thousands or tens of thousands of dollars at least). Between two fine wines, in a weird, snake-eating-its-own-tail way, your enjoyment of the wine is more impacted by how good you think it is than anything else. And the primary drivers of the market, Chinese businessmen bribing government officials or trying to show up their friends, don’t really care anyway.

In such a world, no one can afford Amazon style convenience. Some of the most important information in the market is what all the other middlemen, collectors, and investors are saying about a wine. Since gossip is key pricing information, no one can afford to not be part of it by ordering wine online.

And since most people – even if trying to make a profit – do it out of a love of the wine world, efficiency means missing out on all the conversations they love and exclusivity they enjoy. For someone spending ten thousand dollars on a case of wine, the experience of being taken into a cellar and shown wine that your average person will never even see may be more valuable than the product itself.

The exclusive middlemen of the art world are just as essential. We imagine that people in the art world value the experience of viewing art and feeling like part of an exclusive club just as much as those dealing fine wine. Moreover, the problem the fine art market faces is how to price art dependably. No one wants to spend $100,000 on a work by a hip, new artist only to see no one willing to pay more than $5,000 five years later when people’s tastes change. As a result, as economist Allison Schrager notes, “high-end art is one of the most manipulated markets in the world… galleries manipulate prices to an extent that would be illegal in most industries.”

Galleries go to great lengths to maintain the fiction of dependable prices for the artists they represent. They rarely post prices, and when an item goes to auction, the gallery representing the artist often bids on it to inflate the price. As Schrager shows in this anecdote, the art gallery cartel simply will not let an outsider set the price of fine art:

A few years ago a young art collector from New York I know bought a painting from a New York gallery. A few weeks later she went to the Miami Basel art fair where a celebrity heard about the painting. He offered to buy it for more than 50 times what she paid for it. She refused and he raised his offer to a sum that would mean she’d never have to work again. She explained that she would not bargain with him—any resale of the painting must go through the gallery, so they’ll get a commission and select the price—not her. The young collector knew there would be consequences to making the sale. She may have owned the painting, but reselling it at a profit without the gallery’s permission would blackball her from the art industry. To her, that was not worth the millions she was offered.

The problem for Amazon in the fine art world is that galleries are not just middlemen. Galleries offer an experience and a feeling of exclusivity that is as important as the actual product. Their price manipulation semi-arbitrarily creates powerful brands out of the artists they back in order to bring stability and predictability. Without galleries, the market would be a chaotic mess of erratic prices that would scare off big money.

It’s intuitive to think that Amazon, which specializes in cheaply and conveniently selling commodities, cannot sell something as un-commoditized as fine art. But the opposite is true. In markets where value is so subjective and cache, it is the opaque and exclusive middlemen, wine’s old boy’s clubs and art’s exclusive Manhattan galleries, that make the product a commodity that can be bought, sold, and invested in.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.