Despite humanity’s near-universal case of arachnophobia, we cherish the spider web as one of Earth’s beautiful, organic creations. Spun delicately and dexterously from resilient silk, the web is the most important element of the eight-legged, plump-bottomed arachnid’s livelihood, both providing him with a home and ensnaring his meals.

But what if spiders were to craft their webs under the influence of marijuana? How about cocaine, caffeine or LSD? Luckily, thanks to years of taxpayer-funded research, we have the answers to these important questions.

It all started in 1948, thanks to the curiosity of a Swiss gentleman named Peter N. Witt. A pharmacologist by trade, Witt had spent much of his time researching the effects of various drugs on humans at Germany’s University Tübingen. He shared his small research space with H.M. Peters, a zoologist who studied spiders.

For months, Peters fruitlessly tried to capture the web-building process on film, but as he sat and watched late into the night, he’d often fall asleep and miss the process (spiders typically build their webs between 2AM and 5AM). After one particularly frustrating night, Peters asked Witt to find a way to shift the process to more reasonable hours.

Annoyed by his colleague’s incessant pestering, Witt agreed. He began by addressing the problem the only way he knew how: with psychoactive drugs.

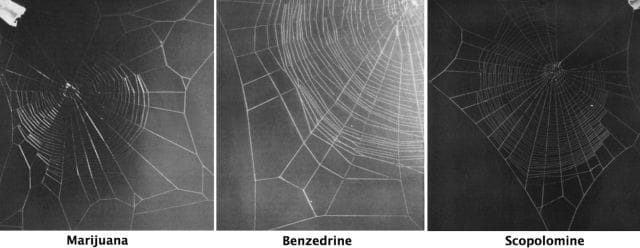

Until then, he’d only worked with humans and “had not the slightest idea how the drugs would affect spiders.” Nonetheless, Witt collected potent doses of several drugs — marijuana, mescaline (peyote), morphine, scopolomine, and Benzedrine — mixed them with sugar water to attract interest, and administered tiny drops of the solutions into the spiders’ mouths (one drug per spider), at various levels of concentration.

The following morning, Peters and his team of zoologists returned sorely disappointed: Witt’s tests failed to change the spiders’ tendency to work on webs late at night. But the results fascinated Witt: the creatures’ mannerisms and web patterns deviated tremendously with each drug administered. At that moment, Witt decided to entirely devote himself to getting spiders high.

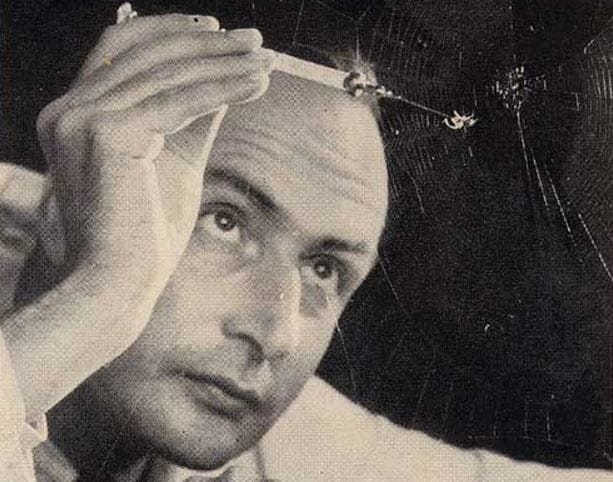

Peter N. Witt sending a spider on a trip (c. 1950s)

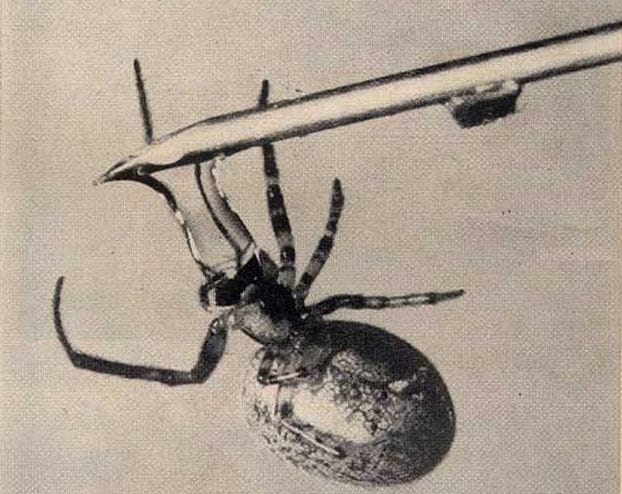

A spider tripping hard (c. 1950s)

“Human subjects are moody, complicated and variable,” Witt wrote in Spider Webs and Drugs, the 1954 publication on his preliminary findings. “Spiders proved to be much simpler subjects.” But spiders also had a practical application: since they had a visually different response to each drug, they could serve as an easy test for identifying unknown drug poisonings in humans down the line.

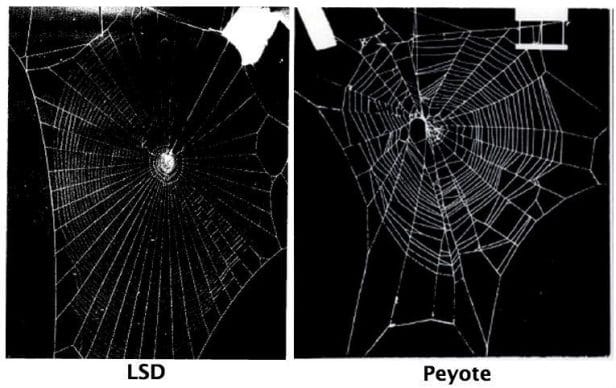

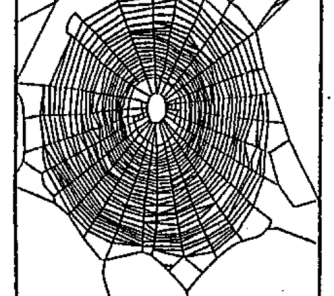

Witt honed his experiments over the years. He exclusively used the zilla x-notata, a garden spider species that spins orb webs; he kept them on a natural diet — one that provided the spiders with sufficient energy, but was also sparse enough to force them to build a new web each night. He also only used female spiders, because males are half the size, eat less, and don’t build webs as often. In subsequent experiments, he added other drugs into the mix — chiefly LSD and caffeine. Each drug produced its own distinctive aberration.

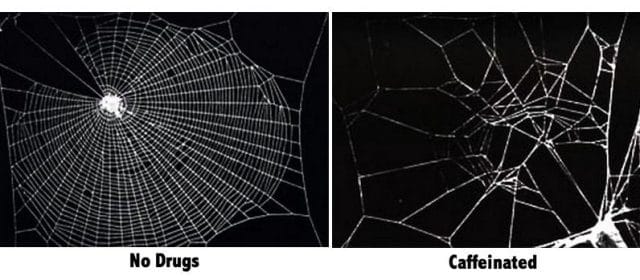

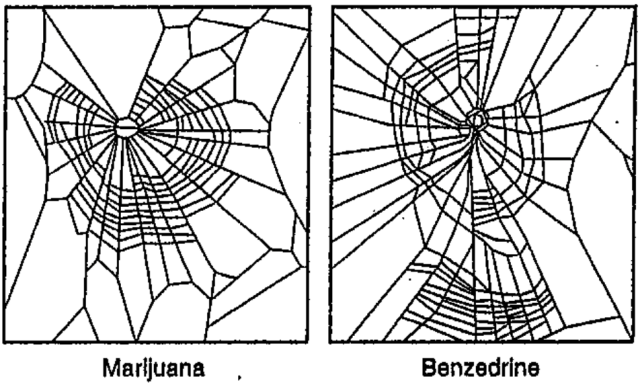

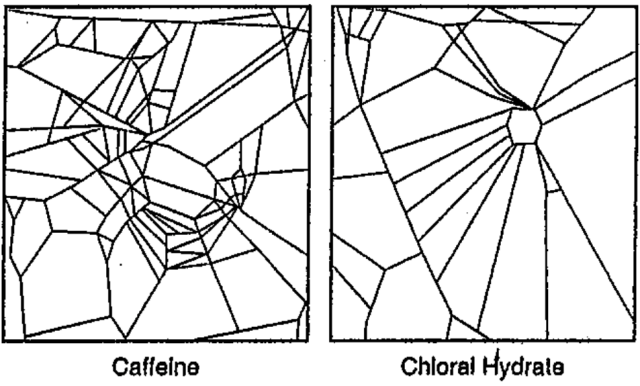

With a 10 µg dose of caffeine, for instance, a spider would build its web much smaller, and the radii (circular threads) would be incredibly uneven and disorganized. At a higher dose (100 µg, pictured below), the spider’s ability to craft a web would essentially go to shit:

Witt found that nearly every drug yielded the same effects, in slightly varying degrees of non-functionality. Spiders dosed with sleeping drugs became “very drowsy,” skipped spinning the longest, most challenging radial threads (those on the outer corners of the frame), and left huge gaps in their webs; Benzedrine caused the spiders to spin a spiral “that zig-zagged like an unsteady walker” and induced the inability to locate precise spots within the web; marijuana made the insects omit altogether the inner part of the web; scopolamine, which has hallucinogenic effects in humans, destroyed the spiders’ sense of direction altogether.

“When a spider’s central nervous system is drugged,” wrote Witt, the insect faltered “as a man intoxicated by alcohol weaves an erratic course down the street.” Only one drug was an exception to this: spiders administered small doses of LSD actually constructed “more orderly” webs (they didn’t, however, fare as well on high doses, as pictured above).

Witt went on to do many other things to spiders — chiefly, launching them into space, frying their nervous systems with lasers, and pumping them full of barbiturates — but he ultimately discontinued his experiments in the late 70s, and passed the torch to the next generation of spider-druggers.

It would take years before Witt’s research was revived. In 1984, J.A. Nathanson, a molecular pharmacologist, published “Caffeine and related methylxanthines: possible naturally occurring pesticides,” a study in which he reanalyzed Witt’s findings — but only those dealing with the effects of caffeine.

In 1995, NASA decided to entirely recreate Witt’s experiments using many of the same drugs — marijuana, chloral hydrate (sleeping pills), benzedrine, and caffeine — on a small army of European garden spiders. Qualitatively, NASA’s results were similar to Witt’s, but NASA researchers went further by quantifying the alterations with computers to measure levels of toxicity.

The scientists’ ultimate findings insinuated that the more toxic the chemical, the more screwed up the web was. Their results, like Witt’s, widely varied:

Of course, dozens of other species and animals have been drugged for the sake of science: rats, snails, goats — even an elephant was given LSD once (it didn’t turn out well). So, why spiders?

Both Witt and NASA cite that other animal testing is “expensive, time consuming, and increasingly restricted by law.” Spiders, on the other hand, are cheap, produce relatively fast outcomes, and, most importantly, give us a physical visualization of the effects of drugs. They’re also ugly, detested, and don’t elicit our sympathy (unless you’re Gwen Stacy).

Ultimately, intoxicated arachnids didn’t really provide us with a tremendous amount of information about drugs — at least, not information that could be readily applied to humans. But one thing is clear: spiders on drugs are much like humans on drugs. If we qualify the skills enlisted by a spider to craft its web (ie. dexterity, precision, depth perception), these are all things humans generally fail at under similar states.

We have only one lingering question: which camp does Spiderman fall into?

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.