“The government should not be able to look at dick pictures,” a young woman says into a microphone.

“If my husband sent me a picture of his penis and the government could access it, I would want that program shut down,” a nicely-dressed older woman says, nodding.

“If I had knowledge that the US government had a picture of my dick, I would be very pissed-off,” a young man in a baseball cap says.

These quotes are from a video montage of man-on-the-street interviews John Oliver made Edward Snowden watch, when Oliver interviewed him in April, 2015. The in-studio audience laughed uncomfortably while Snowden cringed, because, though the people interviewed were oblivious to it, that program does exist. In fact, multiple programs like that do.

Snowden once worked for the National Security Intelligence Agency (NSA), where he says government agents were so accustomed to handling sensitive data, seized through government surveillance programs, that they frequently passed around naked photos of strangers. These programs included PRISM, a mass electronic surveillance data mining program.

In May 2013, Snowden fled the country and leaked thousands of classified documents to journalists, including The Guardian’s Glenn Greenwald. Glenn Greenwald broke the story on PRISM and the NSA’s other programs on June 6, 2013. Snowden was charged with violating the Espionage Act and theft of government property. Since June 23, 2013, he has lived in exile in Russia.

Two years later, he did an interview with John Oliver, in which Oliver showed him a series of interviews of people in Times Square who had no idea who he was, nor what the government programs he exposed were. And then, Oliver asked him what the “over under” was that the guy in a baseball cap had recently sent a dick pic. Before Snowden could respond, John Oliver played the next clip.

“I did, I did take a picture of my dick,” the man said. “And I sent it to a girl, recently.”

Oliver’s point was that Americans didn’t seem to think that government surveillance meant that their personally sensitive data was no longer private. Even though the widespread surveillance program had been exposed — at great personal cost to Snowden, and at the international security risk entailed in releasing the classified information — Oliver was making the point that people still didn’t understand it. For the average American, it might as well have never happened.

Of course, Oliver’s evidence was just anecdotal. Recent research has shed more light on the subject. It turns out that, following the PRISM revelations, internet usage did change. Both Americans and non-Americans significantly reduced their use of search terms perceived as possibly getting them into “trouble” with the government, e.g. “nerve agent,” “dirty bomb.”

But Americans specifically didn’t reduce their use of search terms that were personally sensitive — e.g. “escorts,” “gender reassignment” — even though international users did.

The Pulse of the Internet

Edward Snowden (Last Week Tonight)

The study was authored by MIT professor Catherine Tucker and Alex Marthews of the non-profit Digital Fourth. To investigate the effect of the PRISM revelations on popular internet use, the researchers started by making a list of search terms. The list included those used for “surveillance of social media” by a Department of Homeland Security agency. The researchers claim that “it is […] the most relevant publicly available document for assessing the kinds of search terms which the US government might be interested in collecting under PRISM or under its other programs aimed at gathering Google search data.”

The list also included 50 relatively “neutral” words — the most-searched terms on Google in 2013, and a variety of and a crowd-sourced list of potentially “embarrassing” search terms.

Then they conducted a massive survey, 6,000 respondents per search term, to rate how likely each term was to get the respondent “in trouble” or “embarrass” them with their family, friends, or the government. High-ranking “social embarrassment” terms included “white power,” “viagra,” and “gender reassignment.” (“Larp,” “nickelback,” “body odor,” and “tax avoidance” were farther down the list.) High-ranking “government trouble” terms included: “explosive explosion,” “pipe bomb,” “anthrax,” and “assassination.”

LARP is an acronym for “live action role-play.” It was given an average “friend embarrassment” score of 1.74 by survey respondents. (Verena Dahmen)

The researchers then used Google Trends’ normalized data on weekly search volumes in 2013. They compared search volumes before and after June 6 for “high friend trouble” versus “low friend trouble” terms, and “high government trouble” terms versus “low government trouble” terms.

Following Snowden’s revelations, the average search volume fell for search terms that were perceived as likely to get users in “trouble” with the government (Marthews and Tucker)

Overall the average Google Trends search index fell by roughly 10% for “high government trouble” terms, and went up a smaller amount for “low government trouble” terms.

The Impact Abroad

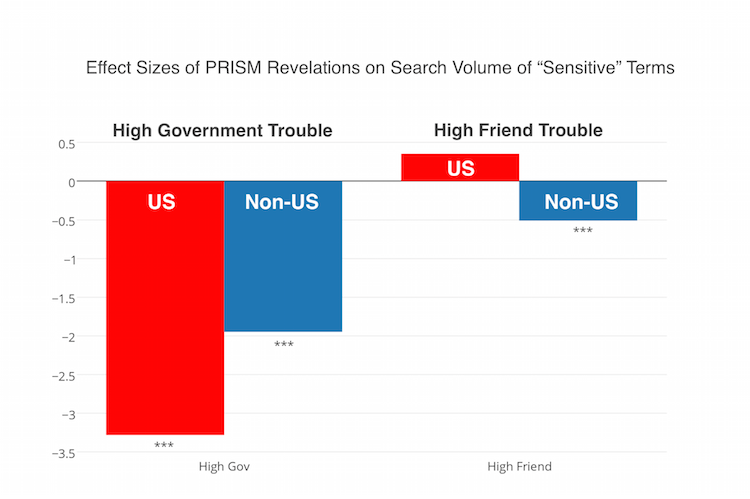

The researchers also broke the data down by country and ran an econometric analysis. In the United States, “high government trouble” terms dropped off at a significant rate, but “high friend trouble” search terms did not.

High government trouble terms were significantly reduced for all search engine users, and high friend trouble terms were significantly reduced for non-US users: ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. For US users, the PRISM revelations had an insignificant positive effect. (Rosie Cima, Priceonomics; data via Marthews and Tucker)

The researchers stress that the fact that there’s any measurable effect in search volume is very interesting. Catherine Tucker, one of the authors and a professor at MIT, has admitted that when she designed the study, she did not expect to see such an effect. From the paper:

“The fact we observe any significant effect in the data is surprising, given skepticism about whether the surveillance revelations were capable of affecting search traffic at such a macro level in the countries concerned.”

The other side of this is that the fact that the change in American usage of personally sensitive search terms isn’t measurable through this technique doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. But it does mean that it didn’t happen to a degree that was measurable through this technique. It also means that, if a “chilling effect” did happen on personally sensitive search terms, it was much smaller than the ones that happened with respect to “high government trouble” terms.

Interestingly, the “chilling effect” on personally sensitive search terms was measurable for international users. For non-US users, the average search volumes for both the “high government trouble” terms and the “high friend trouble” terms dropped off at significant rates. According to the researchers’ analysis, the data supports an interpretation that “the short-term shock in the country where the scandals originated was larger, but that over time the worldwide ramifications of the surveillance revelations became more apparent, and [international] user search behavior shifted accordingly.”

***

Although there is some concern in the sciences about using proprietary corporate data like Google Trends, which is only partially transparent, the study’s findings proved robust to the authors’ falsification checks — which included using different time windows, and controlling for news coverage. And as Motherboard pointed out, the findings are also consistent with a recent PEN survey of writers and journalists:

[According to the survey] writers are […] turning down book deals and speaking opportunities and shying away from writing about certain topics, “including military affairs, the Middle East North Africa region, mass incarceration, drug policies, pornography … the study of certain languages, and criticism of the US government.” Sixteen percent of writers polled by PEN said they won’t do certain Google searches in case it piques the government’s interest; and one in four say they regularly self-censor in email and on the phone.

As Tucker and her co-author, Alex Marthews, speculate in the paper, these effects could have longer-term economic repercussions. If users care about the privacy of certain searches, and feel like they can’t use Google in privacy, they might even take the drastic measure of using a different search engine. Both Tor and DuckDuckGo’s user bases have seen dramatically increased usage since June 2013. And this privacy-driven shift could extend past search engines: if you know that Google is a partner in US government programs that allow for the bulk collection of emails, you might switch to a different email client for very sensitive messages. It might dissuade you from getting an Android phone.

Whether such an economic impact is plausible, or already begun in a measurable way, has yet to be studied systematically. In the meantime, it certainly seems that the revelation of government surveillance has affected people’s behavior, for better or for worse.

“[Our study] helps to establish a common fact for all sides: that surveillance does indeed chill search behavior,” Marthews explained to Motherboard. “We don’t expect people to agree on whether that’s good or bad, but our article shows that this chill is definitely happening.”

Our next post examines why airlines have historically had trouble making money, even though they seem like monopolies. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Rosie Cima. You can follow her on Twitter here.