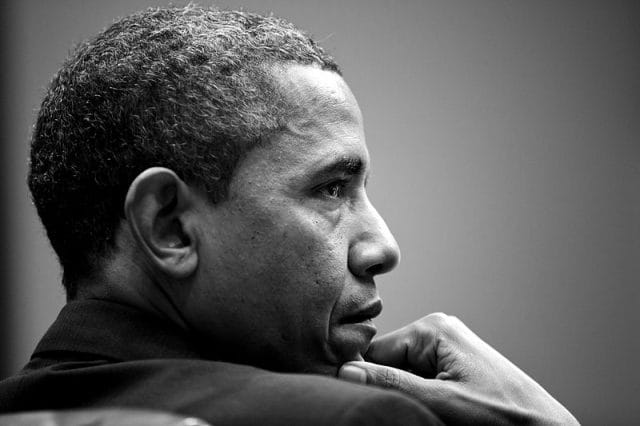

Since Barack Obama first began campaigning for the presidency, people have said some crazy things about him. “He is a socialist Muslim with a radical anti-colonial agenda who was born in Kenya,” for example.

Commentators described the accusations as a racist reaction to an African-American president. Others comforted themselves that they were the ramblings of a lunatic fringe. But polls indicated otherwise. A 201 Harris Interactive poll found that the following percentage of Americans believed about President Obama that:

- He is a socialist (40%)

- He wants to take away Americans’ right to own guns (38%)

- He is a Muslim (32%)

- He wants to turn over the sovereignty of the United States to a one world government (29%)

- He was not born in the United States and so is not eligible to be president (25%)

- He may be the Anti-Christ (14%)

- He wants the terrorists to win (13%)

These beliefs split clearly along partisan lines. Republicans believed the following about President Obama:

- He is a socialist (67%)

- He wants to take away Americans’ right to own guns (61%)

- He is a Muslim (57%)

- He wants to turn over the sovereignty of the United States to a one world government (51%)

- He was not born in the United States and so is not eligible to be president (45%)

- He may be the Anti-Christ (24%)

- He wants the terrorists to win (22%)

Although these are extreme examples, they are typical of how polls about facts show clear partisan bias. In 2012, years after American officials failed to find any signs of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, 63% of Republicans believed in their existence. (As did 15% of Democrats.) Democrats (falsely) underrate economic performance under Reagan while Republicans do the same for the economy under Clinton.

Academics often explain this ideological gap in the realm of facts as a result of partisanship influencing how we acquire and process information. Four economists, however, recently decided to challenge the sincerity of these reported beliefs. (Perhaps they were inspired by the fact that 14% of Americans report believing that Obama may be the Anti-Christ.)

They propose that Americans discuss facts of partisan importance with the same intellectual honesty displayed by arguing sports fans. Basketball diehards from Los Angeles and Chicago exaggerate Kobe Bryant’s free throw percentage and the size of Michael Jordan’s Most Valuable Player trophy collection. So, the economists argue, why do we expect any more honesty from zealous Republicans and Democrats? They see partisan disagreement over facts arising from political cheerleading rather than psychological biases.

To test their hypothesis, they replicated common, fact-based poll questions but gave participants an incentive to tell the truth: Correct answers earned a chance to win cash or a gift certificate. In a first experiment, people were rewarded for giving the correct answer. In a second experiment, participants were rewarded for responding correctly or admitting that they did not know the answer. (The reward for admitting ignorance was only a fraction that of the reward for a correct answer.)

Their results, published as a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper under the title “Partisan Bias in Factual Beliefs about Politics,” suggest that the partisan gap in knowledge of politically relevant facts may be insincere.

In the first experiment, the control group’s Republicans and Democrats demonstrated a partisan bias in their responses for 8 out of the 9 questions about facts such as whether the deficit and unemployment rate rose or fell under President Bush and how the average annual global temperature had changed over time. But among the group rewarded for giving accurate answers, 55% of the Republican-Democrat divide disappeared.

In the second experiment, the economists introduced a slider that participants could use to answer questions dynamically (ie how much the unemployment rate changed during Obama’s presidency from -1% to 3%). Once again, incentivizing correct answers reduced the partisan gap. But when responses of “don’t know” also earned a reward, the partisan gap shrunk further. Participants responded “don’t know” 47.8% of the time, and the partisan gap shrunk from 15% of the scale range to 3%.

The authors explain what that means in practice:

In the case of the question about change in unemployment under Bush, the response scale ranged from –2% to 4%, and the estimates imply that control-group Democrats offered a response that was about .9 percentage points higher than control-group Republicans. Among those paid for a correct response, these estimates suggest that gap was only .4 percentage points, and among those paid for both a correct and don’t know response, it was only .2 percentage points.

One remarkable aspect of the study is just how small of an incentive was needed to dramatically increase the participants’ sincerity. In the first experiment, the reward was a chance to win a $200 gift card to Amazon.com, which puts the expected value of answering a question correctly at under a quarter. In the second experiment, the maximum potential reward was only a few dollars.

The economists see this as good news for democracy. If voters always see the world in Republican or Democrat tinted glasses, constantly believing that representatives of their party performed better than they in fact did, then they won’t be held accountable. But if an incentive of ten cents can reduce this partisan gap by over 50%, maybe democracy has a chance.

On the other hand, when the economists offered monetary rewards for honesty, participants in the study owned up to their own ignorance almost 50% of the time. And when voters despise the other party so strongly that they say that it is led by the Anti-Christ… Even if that is political cheerleading, it probably doesn’t matter that they know the real GDP figures.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.