Flying an aircraft into the fiery maw of a raging wildfire is just as dangerous as it sounds.

Early one morning in August of 2001, Scott Vail received a report of a fire burning in an isolated corner of California’s Eldorado National Forest. The wildfire had caught at the bottom of a deep canyon, and so Vail, then the Forest Service’s Fire Chief for Eldorado, chose to send out a forest helicopter with a ground crew following behind.

Throughout the morning, the helicopter delivered water to the fire’s perimeter, 500 gallons at a time, in support of the crew and the fire engines below. But as the day wore on, winds started gusting off of the fire. Four hours into the operation, a draft caught the helicopter’s empty bucket, swinging it out from under the belly of the aircraft and over its tailboom. The pilot was able to make an emergency landing without damage or injury, but Vail was forced to pull the helicopter and ground crew out of the canyon.

The Star Fire of 2001 would go on to climb out of the canyon and scorch over 16,500 acres across the central Sierra. The helitack crew under Vail’s command escaped crash and flame, but not all aerial firefighters were so lucky that week.

That Monday, some 250 miles to the west, two Grumman TS-2A airtankers had collided while battling a fire near Hopland. The pilots in both planes had been killed.

“Flying a big aircraft through inhospitable terrain with outflow winds is not for me,” says Vail, who has since retired from the Forest Service after a 34-year career. “I liked being in helitack, as helicopters can be more forgiving if something goes wrong, but I don’t spend much time in them if I don’t have to.”

Vail’s trepidation is warranted. Wildland firefighting is dangerous in its own right, even without the addition of military-grade aircraft. Since wildfire fighting became the business of the federal government in 1910, nearly 1,100 firefighters have died in the field. More aggressive firefighting policy and more severe fires have escalated the death rate. According to an analysis by the CDC, over 20 firefighters died each year between 2000-2013. A quarter of these were aviation-related.

That’s a staggeringly disproportionate death toll. Though total employment statistics for wildland firefighters are hard to come by, the number of ground crew working a single wildfire can number in the thousands, while those aboard planes and helicopters are not likely to exceed a few dozen. Aerial firefighting is a risky business.

And it’s a risk that many believe is taken far too frequently. Aerial firefighting—by helicopter, scooper plane, or chemical retardant-bearing airtanker—is dangerous, but it is also expensive, regularly misused, and, as some experts argue, emblematic of a long-standing, but entirely misguided, approach to U.S. forest fire policy. While wildland firefighters and forest fire researchers agree that the “aerial attack” can be an important component of effective firefighting strategy, its imprudent use can come at a steep financial, ecological, and human price.

And for that, we the public might bear some of the blame.

Fly for the Cameras

When a wildfire is raging, ground crew will burn, bulldoze, or hack away combustible biomass in advance of the coming flames in order to starve and contain them. Fireline construction is grueling, necessary, and effective work—and it makes for lousy television.

Not so of fire aviation. When a decommissioned DC-10 soars low over the landscape and empties a bellyful of crimson chemical dust onto the treetops, it may or may not be doing any good, but it certainly looks effective.

“For sixty years now, the sign of active fire protection has been an airplane dropping retardant or a helicopter dropping water,” says Stephen Pyne, a professor of history at Arizona State University and the author of over a dozen books on wildfire. “The public expects it.”

In many cases, the public demands it too. Media optics aside, firefighting authorities are under pressure from the public and policymakers alike to throw everything they can at a raging wildfire—especially when life and property are at risk. A highly visible retardant drop can serve as an insurance policy by elected officials and firefighters against future complaints that not enough was done. Cynics have a term for the unnecessary use of aerial resources to fight wildfire: “the CNN drop.”

Aerial firefighting resources have long served a public relations role. In the aftermath of World War I, the federal government used decommissioned British biplanes to scout for fires and deliver messages, but also to lend a degree of credibility to the newly created Forest Service. Amid a debate between western landowners, who would regularly set small fires to reduce fuel buildup on their land, and the anti-fire foresters in Washington D.C., the planes helped to mobilize support for the government’s new war against forest fires.

That war is ongoing. Adopting uniforms based on those of the U.S. Army, conducting joint research with the military, and using surplus military aircraft after World War II and the Korean War, the Forest Service’s fire fighting machine expanded dramatically in the late 1950s and adopted a decidedly militaristic posture. Even the firefighting nomenclature invited comparisons to the battlefield: the person who directs the firefight is the “incident commander,” the first response is called the “initial attack.”

“Fire was called ‘the Red Menace,’” says Pyne. “That reinforces the sense that you are at war with fire—which was never the case and is a really, really bad idea.”

The Price of Smokey the Bear

Not all forest fires are bad. In fact, as many experts argue, over the last century, we haven’t had nearly enough of them.

It’s a counterintuitive view, but it’s one that Pyne shares with most ecologists and forest researchers. The story goes like this: many ecosystems in the American west adapted to the regular presence of fire. Historically, when these fires burned through a forest, they ripped through the grass and brush. But, absent a more substantial fuel source, the fires would peter out before doing serious damage to the bigger trees. Enter the Forest Service in 1905 with its traditional strategy of fire suppression above all else and you get an unprecedented, century-long build up of fuel.

And while the agency has modified its formal policy in recent years to allow for more “managed wildfire,” according to a report coauthored by one of the Service’s own research scientists, risk aversion and mismanagement within the agency has meant that policy on the ground has changed little. In the last decade, less than half of one percent of all fires have been allowed to burn. This policy, in concert with climate change, is a recipe for massive and massively destructive forest fires.

It’s also a justification for the extensive use of airplanes, says Pyne. “When we have a universal policy that every fire is put out by 10 o’clock the next day, you’re going to have to use aircraft heavily,” he says. And that can get pretty expensive.

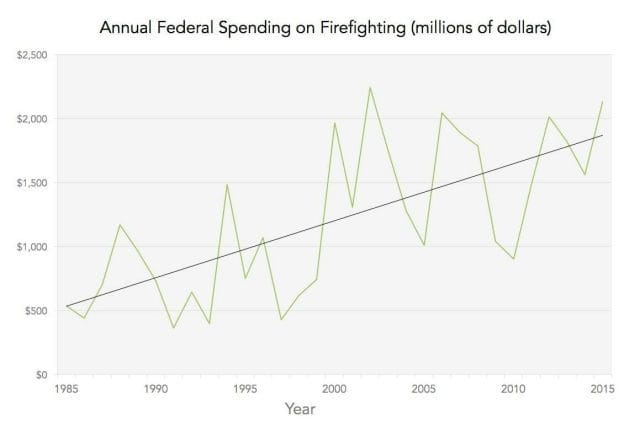

Since 1985, the Forest Service, along with the Bureau of Land Management, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the National Park Service, have collectively boosted spending on all fire suppression activities—both in the air and on the ground—by four-fold, from $533 million to over $2 billion.

Data: National Interagency Fire Center, inflation-adjusted to 2015 dollars.

There are a host of potential reasons for the spending surge—climate change, drought, fuel buildup, and the encroachment of human development into traditional wilderness areas—but whatever the cause, it has crowded out other potentially valuable investments in land management, research, recreation, and future fire prevention. According to a Forest Service report, 16% of the Forest Service’s 1995 budget went to putting out fires. Last year, it was 52%.

Aerial firefighting makes up a sizable share of those costs. A 2009 report by the Government Accountability Office suggested that aviation activities claim up to one-third of all federal firefighting expenditure. Not surprisingly, the largest source of these aviation costs are associated with the aircraft themselves. In the case of the Forest Service, planes and helicopters are most often leased from private contractors, a group that Pyne half-jokingly refers to as members of a “fire-industrial complex…a set of lobbyists for more firefighting.”

The high price tag on these aircraft might be worth the expense, if they were being put to use effectively. But evidence suggests that they are not.

Speed and Access

First, let’s start with a basic, if counterintuitive, fact: airplanes and helicopters rarely put out forest fires.

No matter how large an airplane and its liquid payload may seem from the ground (or on a TV screen), both are generally too small and their aim too imprecise to completely extinguish a serious conflagration. The effect is a bit like spitting on a campfire.

Instead, these aircraft provide support to the ground crew. When a large plane dumps a cloud of red retardant at the site of a forest fire, it helps build a fireline by painting a flame resistant chemical cordon around the flames. Likewise, when a helicopter or a small scooper plane dumps water directly onto an inferno, it is doing so to tamp things down before firefighters on the ground can arrive to encircle the area with firebreaks.

Thus, the conventional wisdom in firefighting circles is that aviation resources should be used in the “initial attack,” those first precious hours of a nascent wildfire’s existence, in order to keep the conflagration in a holding pattern and buy time for the firefighters on the ground.

Matt Plucinski is one of the scientists who helped to make this wisdom conventional. In a series of papers published throughout the late 2000s, the bushfire research scientist at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Organization evaluated the effectiveness of airplanes and helicopters in various firefighting scenarios. According to his results, timing is everything.

“I could summarize my previous research in one sentence, and that’s that ‘small fires are easier to put out than big ones,'” he says. By reaching a wildfire early, aerial firefighters increase the probability that a small, manageable fire will not become a large, unmanageable one. In this respect, he says, the key advantage of aircraft is their speed and their ability to access remote or otherwise difficult to reach fires.

But as the hours drag on and a fire continues to spread, the value of sending out additional aircraft becomes more of an open question, says Plucinski. Raging, acres-wide firestorms tend to rage on regardless of how many buckets of water you dump on them. Choking off such a large fire with extensive firelines has proven effective, but from a scientific perspective, it is nearly impossible to determine what kind of effect a plane or a helicopter has on a large fire—if it has one at all.

Photo Credit: Sgt. Jonathan C. Thibault, U.S. Army

As a matter of policy, the Forest Service has responded to this absence of evidence by prioritizing the use of its most expensive and scarce aerial resources for the so-called initial attack. But as a matter of practice, this has not been the case.

In 2012, a team of Forest Service research scientists reviewed flight records for large retardant-bearing airtankers going back nearly 20 years. The team found that nearly 50% of all tanker flights were used after that initial window of effectiveness had closed. In other words, roughly half of all airtanker flights in the United States during that time period had potentially no effect on wildfire suppression. If true, the implication of the finding is troubling: that’s hundreds of pilots and flight crew needlessly at risk and millions of gallons of potentially toxic flame retardant dumped on our national forests. It also implies an unnecessarily large bill for the federal government.

“Retardant costs about $3 a gallon,” explains Edward G. Keating, a senior economist at the RAND Corporation. “When you’re dropping 3,000 gallons per drop, that’s $9,000 every time.” In contrast, he says, water scooped from a nearby lake is free.

That’s one reason why when Keating and a number of his colleague at RAND were commissioned by the US Forest Service in 2012 to rethink the agency’s aerial fleet, they recommended an emphasis on “scoopers.” Smaller and much cheaper than the large air tankers favored by the Forest Service, these water-bearing planes can deliver more payload at a cheaper price more frequently.

According to Keating, the Forest Service did not refute his findings, but they were nonetheless met with “general grousing.”

“The Forest Service loves its retardant-bearing aircraft,” he says.

The Fault is Not in Our Planes…

Still, as U.S. fire fighting policy evolves, there are small reasons to celebrate.

Potentially misguided aircraft transactions are certainly a marked improvement over the dark days of the early 2000s, when the Forest Service’s dilapidated fleet was falling apart—in some cases, literally. On July 17, 2002, an airtanker carrying retardant near the California-Nevada border broke up in the air. The next day, the left wing fell off an airtanker in Colorado. Between the two crashes, five Forest Service contractors were killed in 48 hours.

“We were crashing two-and-a-half flight crews a year,” recalls retired Fire Chief, Scott Vail. Then, as now, the Forest Service’s entire fleet numbered in the mid-tens. “If you extrapolated that percentage to fire crews, the public wouldn’t stand for it.”

Things have changed in the last decade. In response to the wave of crashes—and later to the criticisms and recommendations leveled by the GAO, by RAND, and by the Forest Service’s own research scientists—the agency has retired its oldest aircrafts, increased the number of water scoopers in its fleet, and chartered an internal “Aerial Firefighting Use and Effectiveness” study. This has all taken place in context of a broader national push by all land management agencies for a coordinated strategy on wildfire management—a strategy that considers not only the financial and human costs of fire, but also its ecological benefits.

On the ground, fire crews have also learned by experience, says Vail, though “too many people had to die to get to where we are.”

But even the clearest policy will not prevent all accidents. Though academics may criticize the overuse of certain aerial resources, Vail insists that the decision to send in the planes or choppers is not an easy decision.

“Am I putting these aviators at risk so that I can take care of something that maybe a handcrew or an engine could take care of it they walked a little further?” says Vail. “That’s the thing that has to go through your mind.”

And even when you make the right decision, things can still go wrong, he says.

The Star Fire that Vail battled in 2001 offers a telling example of the limits of even highly effective wildfire management technique. In response to the early reports of a fire, a helicopter had been dispatched to provide early assistance as part of the initial attack. Vail and his team followed up with a second round of aerial bombardment until the fire reached a certain threshold. Recognizing that additional aircraft would not longer be effective, he pulled back. The response to the fire, in other words, had been by the book. The fire spread anyway.

Though fighting forest fire from the air may seem miraculous, it is no godsend. That, says Vail, has been a difficult lesson for many to learn—and a difficult message for the Forest Service to convey. If airplanes and helicopters are overused, it is because citizens too often expect them to show up and perform the impossible.

“Some of these fires are going to be intractable,” he says. “No matter what you have up there.”

Our next article looks at how Korea’s Kimchi Institute tries to capture the hearts and minds of foreigners through their stomachs. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Want to write for Priceonomics? We are looking for freelance contributors.