In the 1924 presidential election, the most hyped candidate was an egotistical and fabulously wealthy businessman who many politicians did not believe would really run.

That man was legendary carmaker Henry Ford, and the resemblance between his political un-career and Donald Trump’s is striking.

Ford was impulsive, hated experts of any kind, and refused to commit to a platform, specific policies, or even a political party. Instead he ran—for Senate in 1918, and (kind of) for president in 1924—on his reputation as a captain of industry and force of nature.

“I will move my whole force down [to Washington], then they will know that I have arrived,” Ford declared as he announced his political ambitions. He lambasted incompetent politicians, and his inner circle claimed he would save the “average man” from corrupt elites.

Summing up Ford’s appeal, a former governor endorsed him as “a builder.” His supporters called him “master of big things.”

Henry Ford did not want to make America great again in the sense of emulating the past. He hated tradition and claimed to have invented the modern age.

But he did want to reclaim something that America had lost. In a Newtonian example of an equal but opposite reaction, the more the Ford Motor Company advanced the industrial age and drew farmers and immigrants to American factories and cities, the more Henry Ford wanted to preserve America’s small towns, agriculture, and, arguably, white supremacy.

Over time, Ford spent less time at his factories and more at model villages he had built. He collected Americana, established tiny factories whose workers he encouraged to farm, and dreamed of reinvigorating agriculture to draw workers out of the cities and back to small towns.

Ford never wielded the powers of the presidency. But he did control the Ford Motor Company, the most powerful corporation on earth, in his campaign to turn back the clock to an idealized past. To prove his vision could work, he constructed towns, proposed to build a 75-mile long city in rural Alabama, and developed a section of the Amazon the size of Tennessee.

But the future rolled on, and Henry Ford’s genius and all his millions failed to restore his nostalgic vision of American greatness.

The Ford Name

By the time Ford ran for office, he was a celebrity whose name was the world’s most famous brand.

Henry Ford was born in 1863 on a Michigan farm that he was determined to escape. He showed a knack for disassembling and reassembling clocks and pocket watches, which led him to apprentice as a machinist and to later work for Thomas Edison. Ford designed cars for others and for his own unsuccessful companies until he founded the Ford Motor Company in 1903 at the age of 40.

As many have documented, Ford’s accomplishment was to pursue efficiency to the point that middle class Americans could afford a car. (The assembly line is the textbook example, although Ford long insisted on painting all his cars black, because black paint dried faster than any other color.) Ford made dependable cars with no-frills, and by 1921, the company manufactured two-thirds of all automobiles. Ford cars were ubiquitous, world famous, and reaping enormous profits.

What really launched Ford’s celebrity beyond the business world, however, was his decision to pay his workers $5 a day—double the industry standard. Ford’s “five dollar day” was a sound business decision; it incentivized workers to stop walking off the job, which hindered efficiency. But the reaction was a bit like if the Koch Brothers had instituted a $30 minimum wage. As historian Greg Grandin writes, the Wall Street Journal accused Ford of “class treason,” while Ford became a folk hero and one of the “world’s most admired men.”

Ford revelled in the publicity. In Grandin’s words, Ford was “an ‘unrelenting, unremitting’ master self-publicist who… succeeded at spinning his social awkwardness into wise enigma.” He liked when reporters described him and his $5 day as a model for humane industrialization. He disliked when they criticized his racism: Ford had his own self-promotional newspaper and radio broadcasts, which churned out racist comments and conspiracy theories (usually about Jews’ perverse influence) at a rate rivaling Donald Trump’s Twitter feed.

Still, much of the press fawned over the world’s greatest businessman, and both critical and admiring reporters loved Ford quotes like “History is bunk” and “Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black.”Only the president received more press attention than Ford.

“He is like a god of prosperity,” a newspaperman wrote in 1918. He noted that while politicians had to pay for advertisements, the Ford name “rolls over most of the roads of the world.”

Mr. Ford Goes to Washington

Did Henry Ford want to be president?

It’s a difficult question to answer. Ford narrowly lost the race for a Michigan Senate seat in 1918 after he refused to spend a dime on advertisements or do much actual campaigning. He claimed he was running only because President Woodrow Wilson asked him to, although his confidants told the press he considered it a stepping stone to the presidency.

In 1923-24, Ford never announced a presidential run. Yet for months, he refused to discourage friends and supporters who organized a national Ford for President movement. “He is not a potential candidate in the general sense,” his secretary once explained, “but he is not saying he will not be a candidate.”

In both cases, Ford’s campaigns were odd—and unique in American history until Donald Trump’s emergence.

Ford didn’t much care which political party he belonged to. “Any ticket will do,” Ford said in 1918, before ultimately running for Senate as a Democrat whose name appeared on the Republican ticket as well. During his flirtation with a presidential run, no one knew if he would be a Republican, Democrat, independent, or Farmer-Labor candidate.

Pinning down Ford’s preferred policies proved equally problematic. Ford rejected attempts by political parties to bind him to a platform—a surrogate explained that “Mr. Ford will not sign his name on any dotted line.” Instead he promised to use the great ability he had demonstrated in business to tackle challenges as they came.

This proved worrisome to party elites, but Ford found success attacking all politicians. Press releases from the Ford for President movement said that “the leadership of both the Republican and Democratic parties has become the special servant of what is commonly understood…as ‘the interests’.”

People believed that only Ford could liberate the common man from crooked elites. One Congressman complained about hearing poor farmers chanting “‘When Ford comes,…when Ford comes’, as if they were expecting the second coming of Christ.” In an early poll of magazine subscribers, Henry Ford received the most votes of any potential presidential candidate.

This horrified America’s upper crust. The few ideas Ford did propose seemed bizarre—he suggested that since American troops had nothing to do during peacetime, they should enforce prohibition by breaking up speakeasies. He also met with and received support from the Klu Klux Klan and wrote that “the trouble with us today is that we have been unfaithful to the White Man’s traditions and privileges.”

Some critics responded with snark. Ford had once contested claims of his political ignorance by saying that he first cast a ballot for President Garfield in 1884—despite the fact that Garfield was assassinated in 1881. This led one journalist to quip that if Ford’s “memory, busy with so many weightier matters, has mislaid his candidate’s name, at least Mr. Ford once voted, and he knows that there are Presidents.”

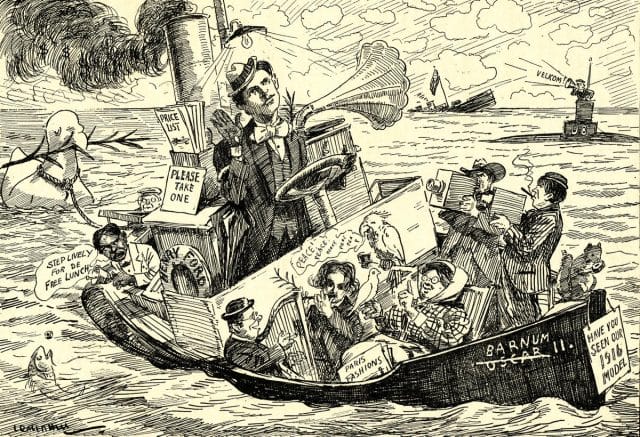

A political cartoon mocks Henry Ford’s “Peace Ship”, which carried Ford and peace activists on an unsuccessful and widely-mocked effort to get Europeans to end World War I.

Others responded with solemn denouncements that electing an “ill-famed anti-Semite” whose comments “have shocked the civilized world” would reflect poorly on the country—and that Ford was a “menace to peace and prosperity.” One company purchased an insurance policy that would pay out if Ford were elected president, and politicians schemed to make sure Ford could not join their political parties.

Yet this did not diminish the mass support for Ford’s candidacy, which his frustrated critics blamed on the media and the burgeoning film industry. As noted by historian Joseph Kosek, just as people see reality television and social media as key to Trump’s rise, critics in 1923 blamed Ford’s “bizarre” candidacy on people’s “movie mind” that demanded “new sensations.”

“If you were a motion-picture producer,” a journalist wrote in 1923, “bent on furnishing a glimpse into the future dramatically, wouldn’t you, now wouldn’t you, choose Henry Ford as your hero?”

In Search of Small-Town America

The Ford phenomenon came to a sudden end when Ford announced his support for President Coolidge. “People agree on the nomination and election of Mr. Coolidge,” he said. “Why change?”

It’s unclear why the enigmatic Ford declined to run in earnest. Perhaps he did not want to actually campaign, or realized he’d likely lose. Other historians speculate that he cared more about winning government approval for his dream project: building a massive, industrial city along Muscle Shoals in Alabama that felt like a small town surrounded by nature.

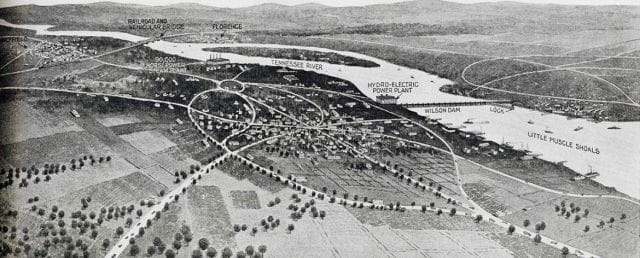

Ford’s vision for Muscle Shoals was a city as thin as Manhattan but five times as long. It would enrichen a destitute area, but more importantly to Ford, it would industrialize the valley without destroying agriculture or creating urban sprawl. The great industrialist saw cities as dens of sin whose trapped residents couldn’t “get a smell of country air.” At Muscle Shoals, residents of the thin city would never be far from nature, and they could work in both the farm and the factory.

At the time, magazines described Ford’s vision as “happy-working-peasants” living in a city of an “All Main Street.” Ford called it a “new Eden” that would be “the great garden and powerhouse of the country.”

Concept art of Muscle Shoals published in Scientific American in 1922

Muscle Shoals was an extension of Ford’s Village Industries: a series of small Ford factories. For each one, Ford either built an idealized small town or located a factory in one, making sure to hire locals so as not to encourage immigration and disrupt the town. The factory schedule explicitly made time for workers to farm.

Ford’s nostalgic goal was to save the American farmer from big cities and integrate him into an industrialized age. “With one foot in agriculture and the other in industry, America is safe,” Ford liked to say. He instructed company scientists and engineers to find industrial uses for agricultural products, especially soy, which he used in the construction of cars. Ford even promoted a “soybean car” until he realized the awful smell would never fade.

The Muscle Shoals project, however, required federal approval that Ford never received. (Congressmen seemed to have a problem with giving a messianic businessman control of a swath of the country.) So Ford decided to build his American utopia in Brazil.

The city he built in the middle of the Amazon was called Fordlandia, and its history is recounted in exquisite detail in Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City. The justification for Fordlandia was to grow rubber for the Ford Motor Company. But as author Greg Grandin makes clear, Ford’s real desire was to prove that he could transform a destitute area into thriving civilization.

In a series of directives, Ford ensured that the rubber plantation followed his vision of unifying small town America with industry. He mandated that all the workers live in well-ordered houses and tend their own flowerbeds and garden plots. He asked American employees to teach traditional dances. He ordered the building of a main street, and to satisfy Ford, his men taught local merchants to specialized in certain goods and act like American shopkeepers.

Fordlandia showed Ford at his best: He built a state-of-the-art hospital for workers and their families and refused to recreate the Amazon’s exploitative, feudal system of rubber tapping.

It also showed Ford at his worst: His efforts to control workers personal lives led to riots, and his poor management choices led to scenarios like two Ford men entrusted with procuring rubber seeds instead hiring prostitutes and embarking on a several week booze cruise.

But Fordlandia was undermined from the start by Ford’s distrust of experts. He put his personal secretary, a trained banker, in charge of choosing a location to grow rubber, and his secretary chose the Amazon—the one place that any botanist would have rejected. Rubber could be grown on plantations in Southeast Asia, where it was not plagued by the predators that co-evolved with rubber trees in the Amazon. In Fordlandia, however, growing rubber trees in tight rows only made it more efficient for fungi and insect infestations to destroy the crop. For years, the workers fought a losing war against nature.

Ford’s utopian city never had a chance.

Looking back at Fordlandia, Muscle Shoals, and Ford’s Village Industries is a cautionary tale about would-be saviors.

Of the three, Muscle Shoals was the most successful. While the government rejected Ford’s proposal, his ideas became the basis for the Tennessee Valley Authority, a central program of the New Deal that improved farming practices and provided cheap electricity to areas like Muscle Shoals.

The Tennessee Valley Authority is considered a model government program, and its proponents copied Ford’s vision of balancing the city and nature, farming and industry. Yet it hardly upended the dominance of the urban model. America’s quintessential economic engine remained New York, with its playbook of increased density, specialization, and immigration. Muscle Shoals became a better place to live, but never an industrial garden that saved small town America.

Ford’s Village Industries met a more ignominious fate. Intended as models for the world, they were shut down as soon as Ford relinquished control of the Ford Motor Company. No one knows for sure if they turned a profit—Ford had shut down the accounting department to spite his son Edsel. But it’s unlikely they made economic sense; even as Ford built them, the central factory that manufactured Ford cars only grew larger.

Fordlandia was abandoned around the same time. Despite a $20 million investment, it never produced much rubber. The city is a peculiarity today, and its surroundings refute Ford’s ideas. While Ford promoted industrial uses of soybeans to support ordinary farmers, large corporations bought the land around Fordlandia from small farmers, cut down the forest, and planted soy. In the United States, applying industry to agriculture has improved efficiency but reduced the ranks of America’s farmers from 20% of the population to under one percent.

Writing in Fordlandia, Greg Grandin concludes that Ford’s arrogance was not that he “thought he could tame the Amazon but that he believed that the forces of capitalism, once released, could still be contained.”

If you swap capitalism for globalization, you have the modern-day promises of Donald Trump.

Trump is an agent of globalization—a businessman married to a Slovene-American model, who licenses the Trump name around the world and sells swanky apartments to the global elite. And now he promises to protect Americans from Chinese labor and Mexican immigrants. His Muscle Shoals and Fordlandia are a border wall and a tariff war with China.

The similarities of the Ford and Trump campaigns show that a slice of America—a country defined by immigration and change—has always been susceptible to authoritarian figures who promise a return to an idealized past. Ford’s efforts to turn back the clock suggest that it’s a doomed pursuit.

If history is any guide, the greatest version of America lies in its future, not its past.

Our next article looks back at the 1970s ad campaign that branded bottled water as “Earth’s first soft drink”. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

Want to write for Priceonomics? We are looking for freelance contributors.