In 2005, Danny Young set the record for the fewest number of votes needed to defeat an opponent in a political race.

Young did not vote for himself. But thanks to votes from his wife and his neighbor, the backhoe operator defeated his opponent, Marty Seeley, two votes to one. Young became a city councilman in Anamosa, Iowa.

Voter apathy and Anamosa’s small size partly explain Young’s underwhelming victory. The real reason is Anamosa’s best known institution: Anamosa State Penitentiary. When officials divided the small town of 5,000 into four wards, one inevitably contained mostly disenfranchised prisoners. Of the 1,400 people in Young’s ward, 1,300 were prisoners.

“Do I consider them my constituents?” Young responded when the New York Times asked about the prisoners in his district. “They don’t vote, so, I guess, not really.”

Anamosa’s city council race may seem like a quirk of small town politics—an absurdity that Leslie Knope would face in Parks and Recreation. But the repercussions of creating political districts that include large prisons extends far beyond Anamosa.

Most prisons built in the last 30 years are located in rural areas, and they mostly incarcerate minorities from urban areas. Since the Census counts prisoners as part of the prison towns, the rural areas seem more populous and enjoy greater political representation. The result is that black prisoners from urban areas boost the voting power of rural, white districts.

That’s a problem a lot bigger than Anamosa. It’s a problem that might prevent America from reining in its gargantuan prison population.

Prison Gerrymandering 101

Understanding how prison populations can distort political representation requires investigating how the sausage of American politics gets made.

The U.S. Census has counted inmates as part of the local population for over 200 years. For a long time, this wasn’t a problem. Most prisons incarcerated inmates near their original place of residence, and officials only used the data to establish how many representatives each state should have in Congress.

States now use Census data, however, when they redraw the lines of their own districts—updating how New York, for example, is divided into 63 constituencies that each elect a senator to serve in the New York legislature. According to Peter Wagner of the Prison Policy Initiative, the short explanation for the change is that the Census data is free for the states.

Data via Bureau of Justice Statistics

This had a distorting effect when America’s prison population exploded in the 1980s and 1990s. When states tried to build new prisons, city residents balked. Politicians in poor, rural areas, however, welcomed prisons as a source of recession-proof jobs. Rebecca Thorpe of the University of Maryland has written about this transformation:

“On a national scale, fewer than half of all prisons were located in non-metropolitan areas in the 1960s and 1970s; however, rural communities developed hundreds of new prisons during the 1980s and 1990s. By the mid-1990s, rural prison projects constituted almost two-thirds of new prison development.”

Since America disproportionately jails minorities, judges sent black men from New York City, Chicago, and other cities to areas like upstate New York, where the Census counted them as part of prison towns. Since only two states allow felons to vote, the result is reminiscent of the Three-Fifths Compromise: the bodies of non-voting blacks inflate the political clout of voters in mostly white districts.

Prisons can distort redistricting without anyone making a pernicious plan. As the below video from the Prison Policy Initiative demonstrates, New York State Assembly District 114 only meets New York’s minimum population requirement of 126,000 thanks to 9,000 prisoners. If the state did not include prisoners as residents, all of New York’s district lines would have to be redrawn, which could turn blue districts red, or vice-versa.

But when state legislators redraw district lines—which usually happens every 10 years, after the latest Census—prison populations offer a new tool for gerrymandering. In at least 33 states, the lack of a bipartisan or independent commission allows the stronger party to influence or decide how to redraw the lines. In those states, as noted in The Wilson Quarterly, politicians can “put prisons in electorally safe districts, freeing up some of [their] party’s supporters in those districts to be drawn into competitive areas where their votes could help tip the balance.”

Jason Kelly of Virginia Tech has looked for signs of legislators gerrymandering districts after the 2000 census. When he investigated states where control of the state senate switched between Republicans and Democrats, he concluded, “On average, we can expect a party that has recently taken control of the redistricting process to draw more than 5,000 prisoners from districts controlled by the other party or marginal districts into their safest districts.”

Peter Wagner of the Prison Policy Initiative is skeptical that politicians so widely and consciously used prison gerrymandering in the early 2000s. In the past, he notes, the census didn’t note the presence of prisoners, which hid the distorting influence of prison populations. When activists in Maryland won a Voting Rights Act lawsuit in the 1980s, for example, the state had to create a district with a majority of black voters. The intent was to allow black voters to elect a black representative. But since disenfranchised black prisoners made up part of the supposed majority, the district kept electing white politicians—a surprising result for those involved that led them to discover the distorting influence of the prison.

Thanks to the efforts of researchers and activists like Wagner, the Census now releases a count of the prisoner population in time for redistricting. After the 2020 Census, this will allow states to exclude prison populations from being falsely included as constituents—if they chose to do so. “It’s geeky,” Wagner says, “but a huge deal.” Prison gerrymandering also now receives more attention, including from high-profile figures like Al Sharpton and state senators.

But politicians also recognize the potential of prison gerrymandering. In 2012, when redistricting in Wyoming threatened to place two sitting state senators in the same district, one offered a solution: move the district’s border to include the 500 prisoners of Torrington Prison and exclude his house. The legislature passed his plan, which saved his seat.

Graphic by Bob Machuga for the Policy Prison Initiative

But the most powerful distortion of prison gerrymandering isn’t political parties flipping a district or politicians protecting their seat. It’s the bipartisan incentives it provides to keep America the prison capital of the world.

The Long Life of the Rockefeller Laws

In 1972, Nelson Rockefeller was governor of New York. He embodied what would become known as a “Rockefeller Republican”: a progressive Republican. During his tenure, the governor made efforts to protect the environment, expanded the State University of New York, and championed drug rehabilitation programs for addicted convicts in place of prison time. Yet decisions he made as governor pushed America down the path to mass incarceration and helped create a situation in which prisons could distort voting.

Like any politician, Rockefeller faced pressure to respond to the surging crime rates of the 1970s. The public was talking about a “heroin epidemic” in cities like New York. The report “The Negro Family,” written by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, an adviser to President Nixon, had officials talking about the “tangle of pathology” among African-American men that led to unemployment, poverty, and crime. Politicians ignored Moynihan’s analysis, which was not publicly released, that the cause of the pathology was racism and oppression and focused on its description of crime and broken families.

Rockefeller eventually decided to abandon rehabilitation and go “tough on crime.” An aide recalls a meeting where “Finally [the governor] turned and said, ‘For drug pushing, life sentence, no parole, no probation.” Soon Rockefeller announced policies like mandatory minimums: penalties of 15 years in prison to life for people caught dealing or consuming drugs even in small quantities.

Analysts and historians disagree on whether Rockefeller promoted the policies out of concern for victims (as he professed) or to appeal to the national electorate. Rockefeller had sought the Republican nomination 3 times in the 1960s, and Gerald Ford appointed him vice president in 1974.

Either way, mandatory minimums went viral. “The Rockefeller drug laws sailed through New York’s Legislature,” Brian Mann reported for NPR. “Other states started adopting mandatory minimum and three-strikes laws — and so did the federal government.” Tough on crime was a decades-long, bipartisan effort. Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton’s championing of Bill Clinton’s Violent Crime Control Act of 1994 still haunts their careers.

These laws set America down the path to mass incarceration. They are responsible for the famous statistic that Americans represent only 5% of the world’s population but 25% of its inmates. Even though whites and blacks use drugs at roughly equal rates, they also packed new prisons mostly with people of color.

Today an increasing number of politicians recognize that tough on crime laws were a mistake—or claim that they are no longer necessary as crime rates have plummeted nationwide. This past summer, Republicans and Democrats in Congress collaborated on criminal-justice reform bills that reduce mandatory minimums and give judges more discretion in sentencing. The rare bipartisan effort, combined with Republican candidates calling for reform during presidential debates, has led to a sense that the tide is turning against mass incarceration.

POTUS outlined framework for criminal justice reform. The need is clear. Bipartisan support exists. Congress has to pass a bill this session

— Eric Holder (@EricHolder) July 14, 2015

Even if Congress does pass a reform bill, however, mass incarceration will barely budge. The bill would only impact federal sentences, and federal inmates represent around 10% of incarcerated Americans.

To end America’s distinction as the world’s top jailer, states will need to repeal or amend their Rockefeller Laws. And at the state level, prison gerrymandering can get in the way.

Prolonging Mass Incarceration

“All politics is local”

– Tip O’Neill, former Speaker of the House

For over a decade, political opposition to Rockefeller Laws did nothing to curb their influence. “New York State’s Rockefeller drug laws… have persisted since 1973,” a New York Times reporter wrote in 2001, “despite an overwhelming consensus that they are inhumane and expensive, clogging the prison system with people who should be in drug treatment.”

When the New York State Senate considered amending the Rockefeller Laws in the 2000s, they did so with support from both parties and often at the urging of the governor. But they faced opposition from two influential senators: Dale Volker, head of the Senate’s Codes Committee, which decides where to build new prisons, and Michael Nozzolio, head of the Crime Committee.

Volker and Nozzolio both represented districts in upstate New York. “The prisons in their two current districts,” Peter Wagner wrote in 2002, “account for more than 23% of the state’s prisoners.” The New York Times reported, “While senators and their aides deny that fear of losing prison population affects their support for the mandatory sentences, it is appropriate to wonder whether economics plays an indirect role.”

During the prison construction boom, legislators from poor, rural areas competed to get a prison. They saw prisons—and the economy that pops up to support families who visit inmates and spend the night—as an economic boon. “We don’t have to sell [prison development] to a community. The community is knocking on our door,” a VP of the Corrections Corporation of America has said. “It used to be ‘not in my back yard.’ Now, they want it in the front yard.”

Academics, politicians, and journalists have pointed to the economic power of prisons—and the lobbying efforts of the for-profit prison industry—as obstacles to ending mass incarceration. But the political consequences of prison gerrymandering, especially when combined with economic incentives, may be even more problematic.

It can be hard to isolate the influence of prison gerrymandering. State senators from prison districts may oppose ending mandatory minimums because they want to appear tough on crime, and legislatures tend only to vote on bills once they are likely to pass. But when Rebecca Thorpe, an assistant professor of political science, attempted to isolate the influence of prisons on voting patterns in New York, California, and Washington, she found that it correlates with legislators’ opposition to reforms that would reduce mass incarceration.

Estimated Influence of the Prison Economy on Opposition to Drug Reform Laws in California

Chart from “Perverse Politics: The Persistence of Mass Imprisonment in the Twenty-First Century” by Rebecca U. Thorpe

It’s also not difficult to find instances of politicians who benefit from prison populations voting to protect mass incarceration or prison gerrymandering. Dale Volker has said that prisoners incarcerated in his constituency send him letters, but he focuses his attention on the correctional workers with whom he has strong relationships. State Senator Darrel Aubertine of New York, who can be seen leading a rally against the closure of one of several prisons in his district in the below video, expressed opposition to a measure that would have counted prisoners at their original residence (not prison) for redistricting purposes.

![]()

The New York state legislature did amend its Rockefeller drug laws in 2004, 2005, and 2009. Despite the opposition from representatives of rural areas with large prisons, policy changes like giving judges more control over sentence lengths, rather than imposing mandatory minimums, have ended the laws’ most draconian mandates.

The result is that New York’s incarceration rate declined by 20% from 2001 to 2011. Yet the state incarcerated some 60,000 prisoners in 2010, compared to around 35,000 in 1985. This points to how far America is from ending the era of mass incarceration—despite consensus that we should do so.

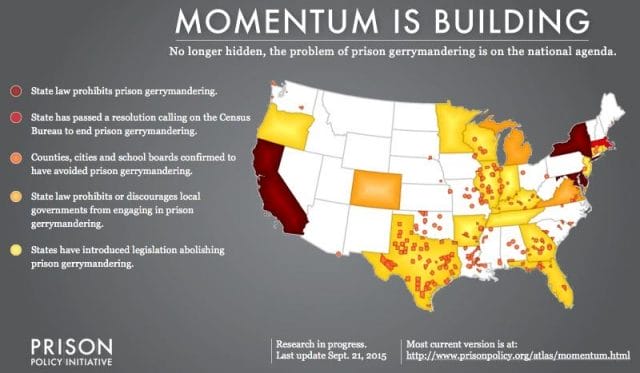

When it comes to mitigating the distorting effect of prisons in rural areas, the key is simply for people to talk and know about it. Four states—New York, California, Delaware, and Maryland—have ended prison gerrymandering by instructing redistricting commissions to remove prisoners from population counts or count them toward their original address. At the local level, Anamosa is one of many areas that has passed legislation or changed its policies to lessen or eliminate the distorting effects of local prisons.

The danger of prison gerrymandering is that it can impact politics in small, important, and unnoticed ways. The chief example is the amendment of New York’s Rockefeller Laws, which was likely delayed by a decade due to upstate prisons keeping prison-loving, tough on crime Republicans in power in Albany. Prison gerrymandering can cause similar delays in criminal justice reform around the country.

But when people learn about the distorting influence of prisons, prison gerrymandering loses its power. Prisons create powerful champions of mass incarceration who can delay or prevent criminal justice reform. The group of people who benefit from prisoners counting toward the vote count, however, is small: people in prison towns and their representatives. The majority of people hate that other voters get more of a say thanks to the prisons.

As a result, prison gerrymandering rarely survives a direct challenge. Peter Wagner says he knows of only one example of a redistricting commission ignoring the complaints of voters who learn that the Census counts prisoners as part of prison towns’ populations.

Once people people see how the political sausage gets made, they want to change it. Exposing the perverse political influence of America’s prisons will be an important step in closing them.

![]()

Our next post is a data-driven analysis of which colleges are best for low-income students. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. You can follow him on Twitter at @amayyasi.