As the clang of a bell echoed down the corridors of a decaying Texas arena, two men interlocked fists and battled for physical supremacy.

The crowd roared with taunts and jeers, scantily-clad cheerleaders bounced in place with plasticine grins, and hulky, shirtless men with handlebar mustaches barked commands from the corners of the ring. It was utter chaos, utter cheesiness — everything one could hope for in a professional wrestling match.

But these battling fellows were not professional wrestlers. They were Herb Kelleher, the 61-year-old CEO of Southwest Airlines, and Kurt Herwald, the stocky, much-younger CEO of Stevens Aviation — and they had gathered here to settle a copyright claim over the slogan “Just Plane Smart.”

Instead of deciding the matter with litigation, Herwald had challenged Kelleher to a good old fashioned arm wrestling duel; the winner, it had been decided, would claim ownership of the slogan.

The CEOs’ 1992 battle was perhaps the most unconventional way a major corporation has ever settled a legal dispute — but it taught us something more: sometimes it pays to conduct business with a sense of humor.

A Very Strange Airline

Herb Kelleher, co-founder of Southwest Airlines

In 1968, Texas businessman Rollin King and his lawyer, Herb Kelleher, formulated a plan to create the world’s weirdest airline.

At the time, the industry was controlled by federal interstate commerce regulations (a flight between San Francisco and New York, for example, would cost the exact same price regardless of the carrier). King and Kelleher’s thought: why not avoid these regulations by operating an airline that solely flies passengers between cities within the same state? Though other Texas carriers battled for nearly three years to keep them out of business, the two men prevailed: In 1971, Southwest Airlines began scheduled flights at much cheaper than market rate.

Southwest’s growth was explosive — in part due to their incredibly strange, oft-controversial marketing ploys. Armed with the motto “Long Legs and Short Nights,” Kelleher hired a troupe of attractive women, gave them uniforms consisting of “hot pants and go-go boots,” and encouraged them to “cheerlead” passengers. When the company went public in 1977, just days after carrying its 5 millionth passenger, its stock was listed on the NYSE as simply “LUV.”

Over the years, the airline also utilized a number of “humorous” slogans to entice customers, including “Love Is Still Our Field”, “The Somebody Else Up There Who Loves You”, and “Grab your bag, It’s On!”

In October 1990, the company’s marketing team came up with what they deemed to be their best catchphrase yet: “Just Plane Smart.” For 15 months, it was generously employed in commercials, and on posters and t-shirts.

Then, abruptly, the party ended.

Even Stevens

Stevens Aviation poses for a team photo

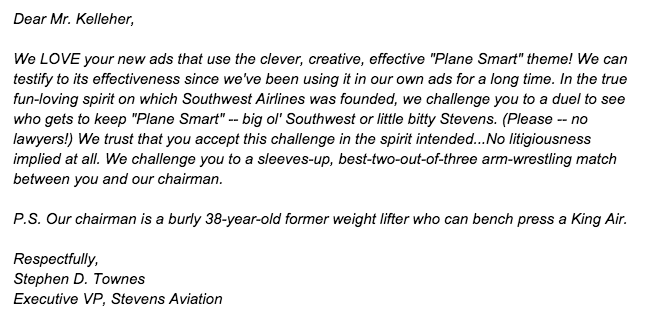

Unbeknownst to Southwest Airlines, a tiny South Carolina aircraft sales company named Stevens Aviation had claimed “Just Plane Smart” as a motto years earlier. When Stevens’ legal team found out about this, they encouraged then-CEO Kurt Herwald to sue. But Herwald, who secretly revered Southwest CEO Herb Kelleher, had another plan — one that wouldn’t waste hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees.

On January 2, 1992, under the guise of his VP, he challenged Kelleher to an arm wrestling duel:

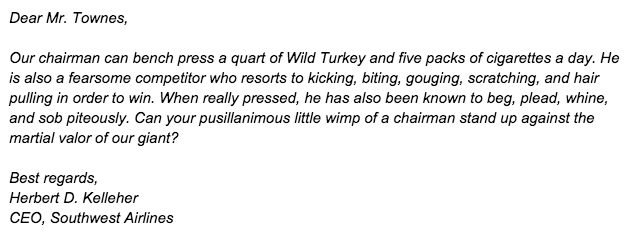

Three weeks later, Kelleher issued his response:

With that, a date was set — March 20, 1992 — and the two men hunkered down to train.

Herwald, a full 28 years younger than the 61-year-old Kelleher, clearly had the upper hand, but he refused to rely on his youth. A series of inter-company promotional videos show him running through the full gamut of bodybuilding exercises: curls, deadlifts, bench presses — often lifting tremendous amounts of weight and profusely sweating.

The Southwest CEO’s training methods were slightly different:

A self-described “true Texan,” the only pulls Herb Kelleher engaged in came out of a bottle of Wild Turkey whiskey. With a cigarette perennially perched between his lips, Southwest’s chief wasn’t interested in the physical rigors of armwrestling training: he’d defeat Herwald with old-school brute strength — the type possessed by a Texan farmhand.

Malice in Dallas

On March 20, 1992, 4,500 attendees (mostly employees of the two companies) packed into the decaying Dallas Sportatorium — an arena once used to house professional wrestling events. Dubbed “Malice in Dallas,” the CEOs’ duel had been heavily marketed, and every news crew in Texas converged to document the results.

As “fans” anxiously awaited the 9 AM start time, the showdown’s terms were announced: it would be a “best of three rounds” competition, with the loser of each round donating $5,000 to the charity of his opponent’s choice (Southwest chose the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and Stevens chose the Ronald McDonald House of Cleveland). The winner would claim sole ownership of the “Just Plane Smart” slogan.

Kelleher, a natural weirdo, revelled in the absurdity of the event. Clad in a bathrobe and flanked by a dozen pom-pomming cheerleaders, he emerged from his multi-colored bus to great fanfare. As the match was on Texas turf, he was heavily favored by the crowd: in the weeks leading up to the event, he’d been “gifted” various items from the community — Wheaties, spinach, Wild Turkey whiskey, and even “anabolic steroids from Mexico” (needless to say, these were not employed).

Herwald was not as keen on theatrics. As elaborated in an interview with The Build Network, he was worried about making himself appear unprofessional; ultimately, he had to rely on a timely pep-talk from a pro wrestler in attendance:

“He said, ‘Look, you’re in a ridiculous situation; the only way you win is if you show the world you’re comfortable being in a ridiculous situation. And he was right. As a young CEO, you worry a lot about impressions and image. But, really, people just want you to be yourself and show your vulnerability.”

As “Smokin” Herb Kelleher made his grand entrance to the theme song from Rocky, Kurt “Killer” Herwald sprinted down the aisle in his red satin robe, greeted by boos and chants of disapproval.

After both had settled in the ring, a bell sounded and the competition commenced.

Instantly, Kelleher announced that he’d injured his arm on the way to the arena whilst “saving a small child.” In his place, Texas’ 1986 arm wrestling champion, J.R. Jones, battled the first round. Herwald was swiftly defeated.

Round two was equally staged. This time, Herwald issued a replacement — his employee, “Killer” Annette Coats. She “crushed” Kelleher, evening the match at one win apiece. The rights to the the “Just Plane Smart” motto would come down to the final match.

Finally, Kelleher and Herwald sat down for an honest face-off:

For 35 seconds, the two CEOs locked arms — each shaking with intensity and effort. Ultimately, Herwald proved to have a little more in the tank, and pounded his cigarette-wielding opponent’s arm into the table.

Stevens Aviation was victorious!

***

In the event’s aftermath, $10,000 was donated to the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and $5,000 was donated to the Ronald McDonald House of Cleveland. Ultimately, the champion, Stevens Aviation’s Herwald, decided that the two companies could share the “Just Plane Smart” slogan (though both eventually abandoned it after the novelty wore off).

The stunt proved to be incredibly lucrative for both parties.

Stevens Aviation, previously a peon in its industry, rose to prominence: it experienced a 25% growth over the next four years, during which its revenues rocketed from $28 million to over $100 million.

Herwald, to this day, maintains that this was the result of the name recognition brought to his company by the armwrestling match. “[My employees] were so proud of the company and so excited for the visibility that Malice in Dallas gave to their work,” he told a reporter. “For months and years after the event, the change to company culture was palpable. Employees felt more connected to one another and to their work.”

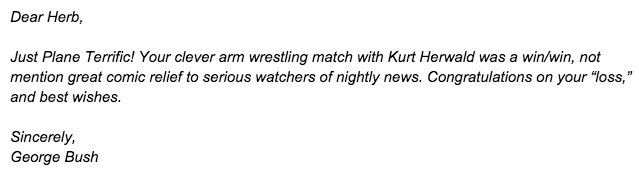

Southwest Airlines earned an estimated $6 million in publicity benefits, and would go on to win the “Triple Crown” of aviation — a number one ranking in customer satisfaction, baggage handling, and on-time performance — later that year. Kelleher also received a special letter from then-president George H.W. Bush:

Ultimately, the two companies’ publicity stunt also saved Southwest from spending $500,000 in legal fees and from engaging in a multi-year copyright battle — one they likely would’ve lost.

But Stevens Aviation’s CEO was never in it to win it. “A lot of businesses these days are using the courts as a competitive weapon — and the courts were never intended for that purpose,” Herwald told reporters shortly after the arm wrestling match.

“Besides,” he added, “there’s too much litigation in business today and not enough leadership. We need more guys like Herb Kelleher who are willing to say we don’t need to go to court all the time.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.