Adolph Spreckels had decided to kill the editor-in-chief of the San Francisco Chronicle.

The year was 1884, and the 27-year-old Spreckels wanted revenge over an article the Chronicle had published about his family’s company, the Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Company. Spreckels’ father was known as the Sugar King because he’d grown rich by monopolizing the sugar trade between Hawaii and the West Coast. The Chronicle regularly denounced the Spreckels monopoly, and a recent article charged that the company was insolvent and that Spreckels and his father had misled and defrauded shareholders.

“Don’t make a fool of yourself,” a friend counseled as Spreckels followed Mike de Young, the editor-in-chief of the Chronicle. But Spreckels ignored him. He walked into the Chronicle office, called out de Young’s name, and shot him with a large, Navy pistol.

The first bullet landed in de Young’s shoulder. He fell to the ground, and Spreckels advanced and fired. By then, de Young had raised a package of books he was holding like a shield, which deflected the shot from his chest to his arm.

At that point, a clerk in the office pulled a pistol from his drawer and shot Adolph Spreckels in the arm, and a Chronicle cashier vaulted over his desk, tackled Spreckels, and restrained him until the police arrived.

Mike de Young survived the attack, and the resulting trial for attempted murder gripped the city. The Spreckels family, in addition to its sugar monopoly, owned railroads, shipping companies, and real estate. They were a household name; the trial resembled the O.J. Simpson trial.

Today, this history is largely forgotten. Instead, San Francisco remembers Adolph Spreckels for his philanthropy, which created landmarks like the Legion of Honor art museum, and for his status as the nation’s first “sugar daddy.” With the riches earned from the sugar monopoly that the Chronicle criticized, Adolph Spreckels married Alma de Bretteville, a working class girl turned nude model who never hid her ambition to marry a wealthy, older man. According to local lore, Alma called Adolph her “sugar daddy.”

A common perception of the richest residents of today’s San Francisco is of entitled, lawbreaking men: technology entrepreneurs ignoring regulations or suing each other for equity, major landlords evicting tenants on questionable grounds, and male-dominated workplaces driving out women.

But if you think entitlement and wealth define San Francisco today, you should hear what the city was like for the heirs of San Francisco Gold Rush fortunes. Because Adolph Spreckels got away with it. Despite shooting an unarmed man from point blank range, a jury declared Spreckels not guilty.

Reporting on the verdict, the Times said of San Franciscans’ reaction in 1884, “Well, money can do anything in this city.'”

The Trial

Spreckels’s attempt to assassinate Mike de Young attracted national attention and condemnation. The New York Times called it a “cowardly assault”, and the L.A. Times called it a “dastardly deed.”

Explaining away the attempted murder charge would not be easy for Spreckels. Multiple witnesses confirmed that de Young was unarmed and had not even turned to face Spreckels before the first bullet hit his shoulder. When the police arrived, they found Spreckels and his loaded pistol.

Of course, the wealth of Spreckels’ father did seem to help. After Spreckels’ arrest, San Franciscans were surprised to hear that he’d been released on bail.

The lawyers for Spreckels argued that Spreckels had acted in self-defense—and that Spreckels had acted during a moment of temporary insanity. As the prosecutor in the case told the jury, the two explanations contradicted each other; it was a defense that lawyers would only make when they had no plausible alternative.

Both arguments also went poorly. Spreckels’ claim that he reached for his gun only after seeing de Young reach for his pocket rang hollow given that he had stalked de Young to the Chronicle office and fired before de Young turned around. And while several friends and co-workers offered tentative support for Spreckels’ insanity defense by testifying that he had seemed moody and unfocused the week of the shooting, another friend of Adolph Spreckels recalled that they gaily shared a drink just hours before the attack.

On the day of the verdict, onlookers packed the courtroom. During the five hours the jury—composed of grocers, merchants, an auctioneer, a foreman, and an undertaker—deliberated, crowds outside the courthouse placed bets on the result, which the New York Times referred to as a “genuine surprise.”

The judge called for order, yelling that the rowdy crowd was “scandalous,” the foreman of the jury read the words “not guilty,” and Spreckels and his friends left the courthouse whooping and celebrating.

What went wrong?

According to the San Francisco Chronicle’s (not at all impartial) reporting, the jury was likely manipulated. Just before the verdict, the jurors, who were visible from the street, seemed to be relaxing rather than debating, and two jury members standing near the window dropped a “paper pellet” that was retrieved by a friend of Adolph Spreckels. Soon after, the same friend made a hand gesture to the two jury members, and a court clerk and another man inexplicably locked themselves in with the jury for almost an hour.

No investigative reporters of the era looked into the trial. The country’s newspapers simply reported the result in bafflement. It’s unclear if the Spreckels family used its fortune to corrupt the jury.

But the story of Adolph Spreckels isn’t exactly a story of the rich trampling the poor without consequences. While Spreckels was heir to one of the country’s largest fortunes, his victim, Mike de Young, was no middle class journalist. De Young owned the Chronicle, the most successful newspaper on the West Coast. This meant he was worth at least several hundred thousand dollars (a fortune at the time), and that politicians regularly sought his advice.

Mike de Young also could not have been that surprised at the verdict. After all, one of the last people to escape justice after shooting a rival at point blank range was his brother, Charles de Young.

A Wild West

When Adolph Spreckels shot Mike de Young in 1884, San Francisco was not far removed from its days of lawlessness and vigilante justice.

In 1848, before the discovery of gold in California, San Francisco was home to only several hundred people. California was a frontier, with few roads or bridges. So when 200,000 people arrived in California in 1849-1850, it took time for San Francisco to civilize from a rough-and-tumble mining town into a well-ordered city. As late as 1856, San Franciscans reacted to the lack of a strong police force by organizing vigilante committees that hanged suspected criminals.

The city’s proclivity for violence was made worse by the fact that the whole country still embraced casual shootings: Alexander Hamilton is America’s most famous duel victim, but through the mid to late 1800s, the duel was an American institution and status symbol. As Barbara Holland writes in Smithsonian Magazine, nearly every American politician, including Abraham Lincoln, participated in duels. They were so common that a famous reverend described the United States as “a nation of murderers.”

This was especially true for journalists, who often wrote for nakedly partisan institutions and received dueling challenges from political opponents. The early history of San Francisco journalism is a bloodbath; one editor reportedly hung a sign at his office that read, “Subscriptions received from 9 to 4; [duel] challenges from 11 to 12 only.”

/p>

/p>

No one embodied this combative journalist ethos more than Charles de Young, the co-founder of the San Francisco Chronicle. As the New York Times wrote in his obituary when he died at age 35, “He was ever on the alert to avoid his enemies. He never stepped into the street without a loaded revolver in his coat pocket, and he usually walked with his right hand grasping the stock.”

When de Young criticized a politician, business executive, or rival journalist in the Chronicle, the spat often spilled into the streets. In one episode, he exchanged fire with a rival editor, then chased him to a police station on another day with a gun in hand, and later even went for his pistol inside a police station when he saw the man in police custody. The courts dropped all the charges against de Young; the sentiment seemed to be “them Duke boys are at it again!”

Another time, Charles de Young demanded that a San Francisco mayoral candidate drop out of the race. When he refused, de Young published an article about the man’s embarrassing past, and the mayoral candidate threatened to do the same. So de Young showed up at a campaign event in his car and shot the candidate twice, nearly killing him. De Young was out on bail the next day, and seems to have never seen a jail cell for shooting the man who became mayor.

A year later, the mayor’s son arrived at the Chronicle office and killed Charles de Young.

To the men of the jury who declined to pass judgment on Adolph Spreckels for killing Mike de Young, the shooting probably looked more like the squabbles of the rich and powerful than a murder—more like the Peter Thiel and Nick Denton feud than a crime.

Why would you anger San Francisco’s most powerful family over something that happened all the time?

The Sugar Daddy

After Adolph Spreckels evaded criminal charges for shooting Mike de Young, their feud transformed from a gun-fuelled conflict between a journalist and a monopolist to a battle for prestige between the social elite and a brash newcomer.

That brash newcomer was Alma de Bretteville, who scandalized the city when she married Adolph Spreckels. Alma de Bretteville had been born poor, but she was determined to marry up. She told people that she had “a great destiny to fulfill,” and she liked to repeat the proverb, “I’d rather be an old man’s darling than a young man’s slave.”

Alma de Bretteville was six feet tall and beautiful, and she achieved local fame after posing nude for artists and taking a gold miner to court for refusing to marry her. (He claimed the two diamond rings he bought her were just pretty gifts.)

When de Bretteville met Spreckels, she was 22 and modelling for a statue, and he was 46 and helping to fund the statue. According to biographer Bernice Scharlach, their first date likely took place on the third floor of The Poodle Dog, a restaurant with a hidden, back elevator and a passageway to a hotel.

The Goddess of Victory monument modelled after Alma de Bretteville in San Francisco. Photo credit: Carnaval.com Studios

Adolph kept many secrets from Alma, the chief example being his chronic syphilis, a condition that Alma did not learn about until her doctor left her side—while she delivered her third child—in order to treat Adolph’s syphilis-induced seizures. (She was lucky he did not infect her and the children.)

But the fact that Adolph had shot Mike de Young was common knowledge. According to Scharlach, de Bretteville was family-focused and, viewing the shooting as a defense of family honor, lionized him for it. After a five-year, secret relationship, Adolph Spreckels married de Bretteville.

This may have made Spreckels the country’s first sugar daddy. Today, tour guides in San Francisco explain to visitors that Alma used the term to describe Adolph, who inherited his father’s sugar business.

The origins of idioms and pop culture terms are rarely clear, and “sugar daddy” is no exception. Alma’s biographer says that Adolph called Alma “pet,” but does not mention Alma calling her husband sugar daddy. Most accounts of the term’s origins also look to early 20th century New York, where the term appeared in a number of play scripts and music lyrics.

Either way, Adolph certainly played a sugar daddy role for Alma, who could finally achieve her upper crust dreams. She moved with Adolph into the city’s most opulent residence and travelled to Paris to buy art and meet artists and creative types.

But San Francisco high society snubbed her—excluding her from the country club attended by the city’s wealthiest wives and her children from the city’s best school.

Alma’s isolation can partly be explained by her refusal to be anything other than herself. She liked to swim naked in her indoor swimming pool, and she had servants deliver entire pitchers of martinis in the afternoon. Her drive for recognition could be gratingly garish—like the disruptive and unending construction project to expand her mansion, or the self-promotion contained in her fundraising efforts for charity—and she enjoyed shocking people. Her nickname was “Big Alma.”

Alma’s snubbing at the hands of San Francisco’s elite also came from another source: her family’s rivalry with the de Youngs. When Alma saw the de Young daughters at social events, she would loudly tell friends, “We haven’t been friends since my husband shot their father.”

Left out of the high circles in which she felt she belonged, Alma decided to buy her way in or create her own. She convinced Adolph to purchase art for the city of San Francisco and donate money for war relief, which helped win her friends—like the Queen of Romania and Parisian artists—who attended her parties.

In response to the de Young’s founding of the city’s first major museum, Alma decided to one up them. The result was the gorgeous Legion of Honor Museum, built on cliffs on the Pacific coast.

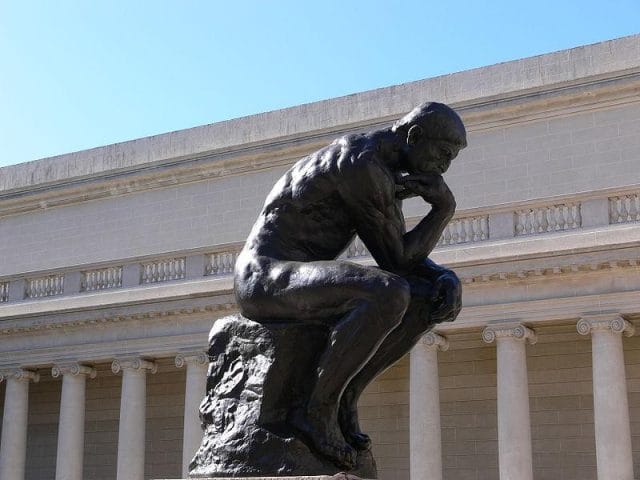

When Alma learned that another museum had a larger collection of Rodin sculptures than the Legion of Honor, she responded, “I’d hoped to beat out that shitty Musée Rodin in Paris. I guess I just wasn’t in time.” But she was still pleased that her philanthropy had established her as a “blessing to all humanity” and elite patron of the city.

More importantly, her elegant, European museum put the de Young to shame. As Alma’s biographer paraphrased her motivations as she assembled the Legion of Honor: “She’d show [the de Young’s] snooty daughters what a real museum should look like”

***

Thanks to Alma’s determination to live a big life, her and Adolph’s name can be found around San Francisco. And their rivalry with the de Young family produced the city’s two famed art museums.

Today, this is how these rich, squabbling folks are remembered. Not for their gunfights and monopolies and political schemes, but for the institutions they left behind: the Chronicle, the de Young Museum, Spreckels Lake in Golden Gate Park, and the Legion of Honor.

Rodin’s “The Thinker” at the entrance to the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. Photo by Andreas Praefcke

Like John Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and countless other wealthy individuals, they invested their fortune shrewdly: donating money to visible causes so that generations later, the halo of that philanthropy would outshine the misdeeds or complicated realities of their lives.

If you keep an eye on the philanthropy sector, you can see which wealthy and controversial individuals are following the same playbook as America’s first sugar daddy and would-be assassin.

It will be interesting to see which of today’s villains turn into tomorrow’s generous benefactors.

Our next article explains why the U.S. government is holding what may be the largest auction ever. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Note: Priceonomics can help your company get better at creating content marketing that actually performs. Software, training and content creation services from Priceonomics. Starting at just $49 / month.