“When you play the game of thrones you win or you die. There is no middle ground.”

Cersei Lannister, The Game of Thrones

***

In 2008, Porsche was cruising.

The luxury car manufacturer generated $13.5 BN in pre-tax profit, and sold a record 98,652 automobiles — a staggering $136K profit per car sold. Even for a luxury brand, the numbers seemed nearly impossible.

Upon closer inspection, $11.5 billion dollars of that profit wasn’t from selling cars — it was from speculating on financial derivatives: Porsche was furtively amassing a sizable position in call options to buy up Volkswagen shares. As a report from the BBC put it, Porsche was “a hedge fund with a carmaker attached.” In 2008, the car business was good, but the financial engineering business was even better.

The company’s CEO at the time, Wendelin Wiedeking, was the highest paid executive in all of Germany. He’d taken the helm of the company in 1993 when the once-fabled car-maker was bleeding money and at the edge of irrelevancy. When he took the position, he negotiated a seemingly moot provision in his contract that would give him 1% of the company’s annual profits as bonus — in the unlikely event the company ever turned a profit. The company was losing $150MM a year at the time; no one could’ve foreseen how lucrative that provision would turn out to be.

The company’s operational performance improved tremendously under Wiedeking’s decade-long management, and the company sold thousands of cars at very lucrative profit margins. And so, the CEO set his sights on an even bigger financial coupe: He’d acquire Volkswagen, the largest car manufacturer in Germany. At the time, Volkswagen produced 50 times more cars than Porsche. But, starting in 2005, the smaller competitor quietly bought up Volkswagen shares and options; by October 2008, Porsche announced that it controlled 74% of VW.

At that moment, the hostile takeover of massive Volkswagen by little Porsche seemed inevitable. But just five months later, Porsche’s plan fell apart: just before completing the acquisition, the global financial crisis worsened and the company ran out of money. Porsche had gone severely into debt to buy out VW; all of a sudden, banks were very anxious to get their $13 billion in loans repaid.

Porsche was left scrambling for a white knight to save it from its financial woes. In a stunning turn of events, that white knight ended up being Volkswagen, the very company Porsche had attempted to acquire.

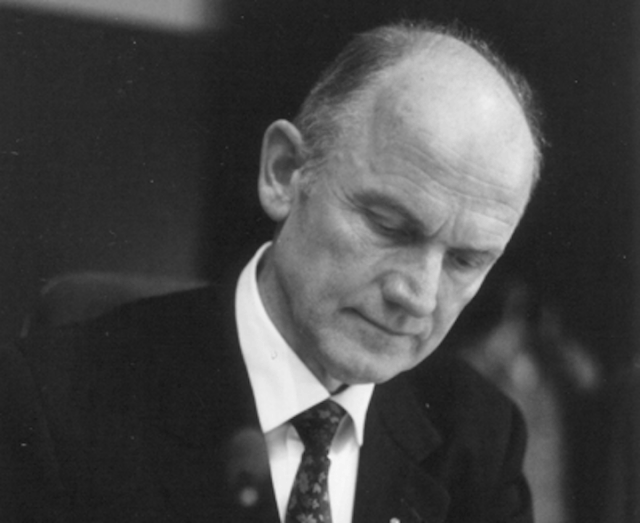

Wendelin Wiedeking: Porsche’s Golden Boy

Porsche, like most German automobile makers, has seen its fortunes rise and fall dramatically.

Founded in 1931 by Ferdinand Porsche, the company was initially an automotive design consultancy that helped automakers design cars. Most notably, the company designed The Beetle, dubbed by Adolf Hitler as “the people’s car,” on behalf of its biggest customer — Volkswagen.

Ferdinand Porsche (tallest person in picture) with a Porsche-designed Volkswagen in 1939.

It wasn’t until 1948, when Ferdinand’s son Ferry Porsche couldn’t find a sports car to his liking, that Porsche began making its own cars. The company’s first model, the Porsche 356, was a success: it went on to sell 76,000 units, and put Porsche on the automotive map. In 1963, the company launched its signature model, the Porsche 911; today, the car is still the linchpin of its lineup.

Ever since Porsche produced its original model, the company’s cars’ reputation vacillated between “luxury precision engineering” and “over-priced junk that breaks down frequently.” In 1993, it was firmly in the later category, and dark times had descended on the company.

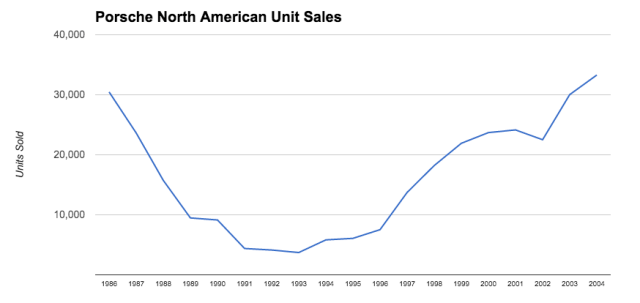

After selling 50,000 vehicles per year in the 1980s, the company’s sales plummeted to 14,000 cars in 1993. In the US, Porsche’s largest market, the company was obliterated. The rising value of the Deutschmark, the increasing popularity of Japanese cars, and a US recession tanked sales to 3,000 cars sold per year, down from 30,000 just a few years earlier. The company was in financial ruin.

This was when 39-year-old Wendelin Wiedeking took over as Porsche’s CEO. A former company engineering manager, Wiedeking sought to revitalize the German automaker by adopting new-fangled Japanese techniques. He operated on a fresh set of principles: manufacture cars with fewer defects, handle less inventory, and hire fewer production workers.

Wendelin Wiedeking via Porsche.com

To implement these radical changes at Porsche plants, he enlisted the help of Shin-Gijutsu, a Japanese consultancy made up of ex-Toyota manufacturing experts. Yoshiki Iwata, the lead consultant, recalls Porsche’s less-than-ideal conditions:

“It was appalling. ‘Where is the car factory,’ I asked myself. ‘It looks like a mover’s warehouse!’ And there were no workers, just apes clambering up and down shelves.”

An extensive revamping of production methods ensued. At the consultant’s behest, Wiedeking symbolically sawed the factory’s storage shelves in half; now there was 50% less shelfspace to keep all this wasteful inventory around.

Though some employees resented being ordered around by consultants who didn’t speak a lick of German, the Porsche factories improved dramatically under Wiedeking: assembly time per vehicle went from 120 hours to 72 hours, defects per vehicle shrunk 50%, the labor required to make the cars fell by 19%, and 30% less factory space was used.

Perhaps most strikingly, Porsche shed its artisanal view of craftsmanship for a more scientific one — something Daniel Jones, a professor at Cardiff Business School, enumerated on in a 1996 New York Times article:

“The traditional craftsmanship for which Germany became famous was filing and fitting parts so that they fit perfectly. But that was wasted time. The parts should have been made right the first time.

So the new craftsmanship is the craftsmanship of thinking up clever ways of making things simpler and easier to assemble. It is the craft of creating an uninterrupted flow of manufacturing.”

When the US and global economy rebounded in 1996, Porsche was a leaner, more efficient company poised to take advantage of increased demand. Sales spiked, especially in the United States: by the end of 1996, the company had broken even, and by 1998, it was turning a $166 million profit.

Wiedeking, who had negotiated in his contract that he would receive 1% of the pre-tax profits as a bonus, received a sizable payday. But his pot of gold was about to get much larger. During the Wiedeking era, the company introduced a slightly more affordable sportscar (the Boxster), and an SUV (the Cayenne), the latter during a time when Americans were gaga for SUVs. These introductions effectively tripled the revenue of the company.

Note: Wiedeking took over in 1993. Data via Porsche.com.

By 2005, the company’s revenue had jumped to $10.3 billion per year, compared to $1.7 billion in 1993. The company made a whopping $1.9 billion in profit, entitling Wiedeking to a bonus of around $20 million. In 2006, every employee received a $4,655 bonus.

Around this time, Wiedeking started grappling with what to do next. According to his philosophy, the company needed to be actively working on something new, otherwise it would atrophy resting on it’s laurels. He recalls his process:

“…I just started to talk about visions for 2005 and 2010. Where will the company be in 2005 and 2010? In 2002, we introduce the SUV. What will we do then? This is, again, my job, because a company must grow. If a company is not able to grow, it is not able to survive. If you stagnate, I think, that’s the beginning of the end.”

At the onset of the 21st century, Porsche had emerged from a crisis stronger than ever. Operations were modernized, new products were selling strongly, and profits were at an all-time high. As recalled by then-CFO Holger Härter, Porsche had launched these products and invested in operations without using any debt:

“We learnt the hard way that banks are there for you when you don’t need them, and when you do need them, they’re no where to be seen.”

And yet, the very same CFO and Wiedeking would forget this lesson only a few years later. The company would borrow billions of dollars as it sought out it’s next conquest: the acquisition of Volkswagen. And, just as CFO Härter’s observation suggests, when Porsche needed the banks the most, they would be nowhere to be found.

The Prize of Volkswagen

In 2005, Volkswagen had the dual privilege of having a depressed stock price and being an important partner for Porsche. Though the company had $123 billion dollars in annual sales, its annual profits were only around $2.2BN and it’s market capitalization only around $17BN. It was widely considered by the financial community to be a pretty crappy company, which is why it was trading at such a low multiple of revenue.

Since Volkswagen was trading relatively cheaply for a company with $120 billion in sales, there were rumors that at US corporate raider like Kirk Kerkorian would make a play at acquiring them — or worse yet, that an American or Japanese car company could swallow them. There were, after all, a lot of companies out there that could shell out $17BN.

Though Porsche had always had a close relationship with Volkswagen, over the years Porsche had become increasingly reliant on its larger counterpart. Most notably, the Porsche Cayenne SUV, responsible for almost a 1/3 of the company’s sales by 2005, was built using the VW SUV chassis — a move that saved Porsche hundreds of millions of dollars. Porsche’s 4-door soon to be released sedan, the Panamera, would also be built on a VW chassis. These new Porsches were essentially fancy Volkswagens with a Porsche engine dropped in.

With this context in mind, on September 25, 2005, Porsche announced that it was paying $4.2 billion to acquire a 20% stake in Volkswagen. Though this was a sizable part of Porsche’s $6.0 billion cash reserve, the transaction would make it very difficult for a corporate raider or competing car company to swoop up Volkswagen, and thusly compromise Porsche’s ability to build cars on Volkswagen’s platforms. In his initial announcement, Porsche CEO Wiedeking made it clear that this minority position was taken just to stave off potential hostile takeovers. Porsche, he adamantly stated, would not be trying to take over the company:

“Our planned investment is the strategic answer to this risk. We wish in this way to ensure the independence of the Volkswagen Group.”

The financial markets were baffled by Porsche’s acquisition of Volkswagen shares. Why was a sports car company pouring so much money into a struggling mass-market car company? It seemed to be the equivalent of a company like Hermes announcing it was taking a large stake in Old Navy.

“‘Porsche told us that they were going to invest back into the company rather than pay higher dividends,” wrote an German financial analyst at Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein. “Now they’re investing into one of the least profitable car companies in Europe.”

The Economist weighed in on CEO Wiedeking’s move — somewhat prophetically, it turns out:

“Mr Wiedeking is one of those rare beasts in the corporate jungle who have not yet had their come-uppance. He is widely revered for his forthrightness and his leadership of Porsche, from the dark days of near-bankruptcy in 1993 when he took over, to years of growth and glowing results today. So it would be a pity if this David overreached himself and fell victim instead to another phenomenon, known as the Peter principle: promotion beyond one’s level of competence.”

There another thing, too: In 2005, it was technically impossible for Volkswagen to get acquired by anyone because of something called the “Volkswagen Rule.” The essence of this rule was that the local German government of Lower Saxony owned 20% of Volkswagen and could prevent anyone from acquiring company without their permission, or anyone from having more votes than them over shareholder matters.

However, this law was incompatible with European Union laws that barred capital restrictions like this, and there was reason to believe that it would be soon repealed. When this happened, Volkswagen would be fair game for an acquisition. With its 20% share in the company, Porsche made it less likely that anyone else would be able to buy Volkswagen in the event of a repeal.

One year later, in August 2006, Porsche modestly increased its stake in Volkswagen from 20% to 25%. Moreover, the company started actively lobbying for Germany to repeal the Volkswagen Rule so that Porsche could “take full advantage of [its] rights as a shareholder.” Publicly, Porsche still claimed to not be interested in an acquisition.

By November of 2006, Porsche had increased its holdings in Volkswagen to 29.9%. A Businessweek headline trumpeted “Porsche’s ‘King Looks to Expand Empire” (or course, referring to Wiedeking). As recounted by the New York Times, Wiedeking began discussing Volkswagen as if he were already its boss:

“‘We could be passive board members or active board members,’ he said at a meeting that was supposed to be about the performance of his company. ‘Our intention is to be very, very active members of the supervisory board.’

‘We believe that if anybody can stand up to Toyota, it is Volkswagen…There will be some changes — there have to be some changes, no doubt.’

Buying a stake protected Porsche’s access to VW factories. Besides, Wiedeking grins, ‘the share price was cheap.’”

By now, another of Porsche’s reasons for purchasing Volkswagen shares had become apparent: Porsche thought the company was cheap, and it was getting a good deal. In interviews from around this time, Wiedeking refers to Volkswagen as a “goldmine” with lots of opportunity to make the kind of operational improvements that turned Porsche around years earlier.

“Turning around Volkswagen” was to be the next grand project for Wiedeking and Porsche.

As Porsche continued to state publicly — and vociferously — that it had no intentions to take over the larger Volkswagen, its actions indicated otherwise. In March 2007, Porsche announced it would increase its share in Volkswagen to 31%. By now, Volkswagen shares were trading at twice the price from when Porsche started acquiring them two years prior. It was getting expensive to buy Volkswagen.

A year later, in March 2008, the Porsche supervisory board gave the company authorization to increase the company’s share in Volkswagen to 50%. By this point, Volkswagen shares had tripled in price from three years before, when Porsche started buying them.

Volkswagen Becomes the Most Valuable Company in the World

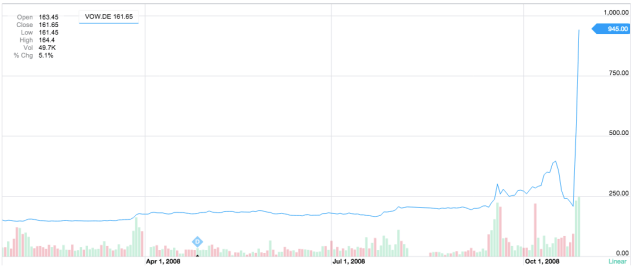

As Porsche slowly bought up Volkswagen shares, the financial markets reacted in two ways. First, the price of Volkswagen shares continued to trend upwards — despite the company’s poor performance. This was based on the belief that Porsche would continue to buy up shares and drive demand for the stock upward.

Second, there were many who felt that Volkswagen’s share price was a case of “the emperor has no clothes” and that the Volkswagen stock price would soon fall. The price was artificially high based solely on the expectation that Porsche would keep buying shares in Volkswagen — not because of anything fundamental about Volkswagen. Given that the Volkswagen Rule was still in effect (and that Porsche publicly stated it wasn’t interested in merging with Volkswagen), many analysts were betting that Porsche would soon stop acquiring Volkswagen shares, and that their value would plummet.

In the truest sense of the term, the Volkswagen shares that Porsche acquired were only valuable “on paper.” That is, if Porsche tried selling any of these shares, the value of its Volkswagen holding would likely drop because the market expectation that Porsche would continuing buying Volkswagen would. At the same time, buying more shares in Volkswagen would continue to be expensive because that would mean Porsche continued to prop up the price.

By 2008, the full effects of the Financial Crisis had hit public markets and it was seeming less than likely that Porsche could borrow enough money to buy up shares of Volkswagen. That fall, Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, and Washington Mutual collapsed. Almost every American bank received a cash infusion from the US Government to avoid insolvency. After years of lax lending practices, banks stopped lending money.

As a result, Volkswagen became one of the most shorted stocks on the market. By October 2008, almost 12.8% of the shares were being shorted with the hope that the price would fall and the shorters would make a profit.

On October 20, the financial publication Barrons published a story about VW titled “The World’s Most Overvalued Stock” and surmised that Volkswagen shares would “likely drop like a Beetle pushed from a cliff” once Porsche stopped purchasing the company’s shares.

The timing of this article couldn’t have been worse.

On October 27 2008, Porsche dropped a bomb on the financial community: it had again raised its stake in Volkswagen — now to 42.6%. Moreover, it had secretly purchased “cash-settled” options to purchase another 31.5% of outstanding Volkswagen shares. Combined, Porsche had now corned 74.1% of all Volkswagen shares! Moreover, after years of denying its intent to acquire Volkswagen, it now finally stated it intended to pursue a “domination agreement” — or 75% of the shares. In doing so, the $12 billion sitting on Volkswagen’s balance sheet could be used by Porsche to finance this acquisition.

For the short sellers, this was a disaster. Not only was Porsche continuing to buy up Volkswagen, which drove up its price, but since Porsche and the Lower Saxony government controlled 94.1% of the Volkswagen shares together, there were practically zero available shares on the market for the short sellers to cover their position.

The Volkswagen share price shot up from $200 per share to $500 per share in one day. The following day, the shares skyrocketed to almost $1,000 per share. For a brief moment on that day, Volkswagen was technically the most valuable company in the world.

Volkswagen stock price in for the first 10 months of 2008.

Short sellers lost tens of billions of dollars over those two days. On the third day, Porsche agreed to make 5% of its shares available to the market to provide liquidity to buyers (and presumably turn a massive profit on those shares). Only then did Volkswagen shares return to more earthly levels.

This maneuver of secretly buying shares would have been (and still would be) illegal in the United States. In Germany though, where Porsche is based, it was likely legal. Normally, it would have had to disclose its growing position, but it used “cash settled” options, which technically wasn’t considered “buying shares” in the company. That meant that the underlying asset of the derivative was cash equal to the the price of a Volkswagen share — not an actual share. Moreover, it bought these options in small amounts spread out among six different banks. It was so convoluted that no individual person knew the extent of Porsche’s move.

Porsche was at the verge of completing one of the most audacious acquisitions ever. It had gained control over 74.1% percent of the shares of one of the largest companies in the world. Moreover, when it reached 75%, it would attempt to gain access to Volkswagen’s cash reserves. And if the “Volkswagen Rule” was repealed (as was widely expected), Porsche would easily be able to own Volkswagen outright.

But none of this happened. Instead, over the next few months, Porsche’s plans fell to pieces.

Meanwhile at Volkswagen

“According to rumour, Ferdinand Piëch likes to run chickens off the road in his Volkswagen Touareg. Whether that is true or not, he certainly tends to ride roughshod over humans, metaphorically at least.”

— The Economist on Ferdinand Piëch, Chairman of Volkswagen

***

If there is a Vladimir Putin-type character in the automobile industry, Volkswagen Chairman Ferdinand Piëch is a good candidate. Known for ruthlessly firing Volkswagen senior executives and CEOs, and buying up luxury sports car companies on a whim, Piëch was running Volkswagen as his own personal kingdom. After decades at the company, he had transformed second-tier maker of unreliable German cars into a stable of powerhouse automotive franchises with over a hundred billion dollars of sales per year. Piech’s autocratic rule had made Volkswagen a force to be reckoned with.

But to everyone’s surprise, Ferdinand Piëch appeared to give up Volkswagen without much of a fight. At the beginning of 2006, Piech announced he would resign from the board of Volkswagen when his term ended in 2007 in order to make way for Porsche CEO Wiedeking and CFO Härter.

While uncharacteristic, it appeared to all that perhaps he had recognized his time running Volkswagen was coming to an end.

But Piëch would not end up stepping down. Instead, he would remain behind-the-scenes and manipulate the process so Volkswagen would end up buying out Porsche at the 11th hour — after nearly every analyst had assumed that Porsche was acquiring Volkswagen. In the end, Piëch would get the job that he’d always vied for, but that had eluded him for years: He’d get to run Porsche.

Despite his last name, Ferdinand Piëch is actually the grandson of Porsche’s founder, Ferdinand Porsche. By virtue of this lineage, he was the second largest shareholder in Porsche.

During this episode, Piëch sat on the boards of both Porsche and Volkswagen. While running Volkswagen, his Porsche holdings were becoming very valuable; as Porsche bought up shares in Volkswagen, he made billions of dollars.

To say this was a conflict of interest would be an understatement.

***

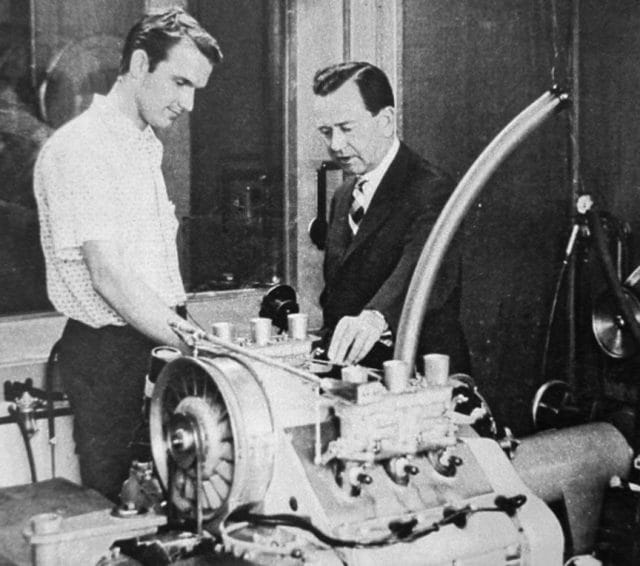

Ferdinand Porsche, the founder of the eponymously named company, had two children: a boy and a girl. The girl married a boy with the last name Piëch, hence half the heirs to to the company have the name Piëch, and the other half more fortuitously retain the Porsche surname.

Ferdinand Piëch, the grandson of the founder, was born with a 10% stake in Porsche — the same as the rest of the grandchildren. He entered the family business in 1963, and, by 1971, became Director of Engineering. As such, he was the leading contender to succeed his uncle as CEO of Porsche.

Ferdinand Piëch (on left) with this uncle Ferry, the CEO of Porsche. Image via Stuttcars.com.

However, family squabbles would prevent this from happening.

As sometimes happens with family businesses, things were in a bit of a disarray by the third generation. In the case of Porsche, the acrimony had grown so bad that in 1970 the family decided no member of the Porsche-Piëch clan would be allowed to play an active role in the management of the company. Instead, the family would continue to run the board and retain 100% of the voting shares in the company.

For members of the Porsche family relaxing with their trust funds, exiting the management of the family business was all well and good — but it meant that Ferdinand Piëch, the heir-apparent to running the company, had to find a new job. In 1975, he joined Audi, a small car brand owned by Volkswagen, as the Head of Technical Development.

Ferdinand Piëch had also been the instigator of much of the family’s drama. In 1972, as a married man with five children, Piëch struck up an extra-marital affair with Marlene Porsche — the wife of his cousin and fellow heir, Gerd Porsche. Piëch left his wife for Marlene, and they cohabited for twelve years and had two kids together (during this time, Piëch also fathered two children with other women).

You can imagine that taking up with your cousin’s wife might make things awkward at Porsche-Piëch family reunions and company board meetings. Many family members suspected Piëch did this solely to gain access to the company shares that Marlene received in the divorce, though this fear never materialized: in 1984, Piëch left Marlene for their 27-year old nanny, Ursula. They are still married today.

At Audi, Piëch was credited with integrating the Quattro all-wheel-drive system into the cars, and turning the company into the sporty luxury brand it is today. In the mid-1980s, reports surfaced that the cars were accelerating erratically and causing serious injuries; Audi had to institute a massive vehicle recall in the US. When Piëch brusquely responded — “We must teach Americans how to drive” — sales of the company’s cars fell by 50% within a couple of years.

In 1988, Piëch became the CEO of Audi. By 1993, he was CEO and Chairman of the parent company, Volkswagen. At the time the company was losing over a billion dollars a year and was reportedly just three months away from bankruptcy. Piëch brought the company back from the dead: he cut costs by reducing the number of vehicle platforms used from 12 to 4, brought in General Motors “cost cutting ace” Jose Ignacio Lopez, and swiftly taught himself the politics of dealing with labor unions and the German government. Instead of laying off workers, he negotiated a 20% reduction in working hours and lower salaries.

He also tremendously grew the company’s market share in the US and Europe with the introduction of cars like the “new” Beetle and the VW Passat. By 1998, he’d transformed Audi into a legitimate competitor of Mercedes and BMW. But, as recounted in a Businessweek article, this turnaround came at a cost:

“Piëch’s visionary leadership has a dark side. VW’s achievements since 1993 have come in a virtual autocracy.

Moreover, his iron grip on VW means there are few checks and balances on his decisions. Piëch has shrunk VW’s management board to just five members, from nine before he took the top job. He holds personal responsibility for R&D, production, purchasing, and the VW brand–areas typically assigned to individual directors.”

With his staff, Piëch did not tolerate dissent. During his time at Volkswagen, he fired over 30 board members, as well as the CEOs of Volkswagen and Audi. At the tail end of 1994, a year after Piëch was named CEO, a group of Volkswagen managers submitted their thoughts to the then-Chairman of the board: “this company is run by a man with psychopathic traits.” In one meeting, a manager made the mistake of questioning a policy of Piëch; Piëch’s icy response: “I’m going to remember your name.”

But under Piëch’s command, Volkswagen thrived. So much so, that they could afford to buy up a slew of sports car companies. In rapid succession, the company acquired Bugatti, Lamborghini, Bentley, the assets of (though not the brand of) Rolls Royce, in addition to brands like SEAT, Skoda, and Ducati. In this era, Volkswagen became a global car powerhouse on par with Toyota or General Motors.

In 2002, Piëch reached the mandatory CEO retirement age of 65; while he stepped down as the CEO, he remained Chairman and retained dictatorial power. Union leaders, German politicians who oversaw the government’s stake in the company, and top executives were all hand picked as “Piëch-loyalists.”

All this is to say it was surprising that Piëch was sitting by idly as the Volkswagen Empire he had built with an iron fist was being devoured by some upstart who was running Porsche — the family business that Piech was deprived of taking over.

Throughout the process of Wiedeking and Porsche slowly acquiring their stake in Volkswagen, Piëch was publicly silent on the issue. Not only that, but he sat on the boards of both companies, so he was very much aware of what Porsche was doing. Since he was one of the largest shareholders of Porsche, observers noted he may be selling out Volkswagen to Porsche so that he could profit from the move.

In 2006, with two years left on his CEO term, Piëch announced he would be stepping down from the Volkswagen board when his time expired. It would seem that he had capitulated to Wiedeking and Porsche. But as that two year period came and went, Piëch soon reversed his decision.

It would seem that Piëch was just biding his time.

Porsche Crashes in the Final Lap

Porsche race car in 1969. Image via Stuttcars.com.

By the end of 2008, Porsche had acquired 42.6% of Volkswagen and had the option to acquire 31.5% more. However, in this process the company had also acquired $13BN in debt to finance the acquisition.

Volkswagen stock had appreciated substantially, and the company had made a paper fortune on these financial trades; meanwhile, speculators shorting Volkswagen stock had lost tens of billions of real dollars. Moreover, once it acquired 75% of Volkswagen, the company’s $12BN cash reserves would become available to Porsche — assuming that the Volkswagen Rule would be lifted soon.

Wiedeking, the CEO, and Härter, the CFO, were hailed as financial geniuses. Arndt Ellinghorst, an analyst at Credit Suisse, called Porsche “one of the most sophisticated investors on the planet, as well as being a car maker.” The Economist humorously noted:

“Great cornering and eye-popping acceleration make Porsche’s cars popular among thrill-seeking bankers and hedge-fund managers. Now its clients are discovering that the carmaker itself has an unexpected talent for cornering markets,” as they reported that Porsche made between $7-15BN from the short squeeze.”

But in reality, the company was actually in a very tough position. Their primary asset was the shares they held in Volkswagen. Those shares were only valuable because of the market’s expectation that Porsche would continue to buy up Volkswagen stock; and if they did, it would be very expensive to buy the rest of the company. If Porsche stopped buying up Volkswagen shares, the price of Volkswagen stock would plummet, the value of most of Porsche’s assets would fall, and the company would experience massive losses.

This scenario would look very bad for Porsche’s creditors — and by now, there were many. By Spring 2009, Porsche had accumulated $13 BN in debt. This wasn’t an enormous amount of debt considering they were making $2BN operating profit a year from selling Porsches, and owned more than half of Volkswagen, but in order to pull off buying the rest of Volkswagen, they’d need access to a lot more capital.

And precisely when Porsche needed banks the most, banks stopped lending money. The words spoken by the company’s CFO years before — “banks are there for you when you don’t need them, and when you do need them, they’re no where to be seen” — now seemed prophetic.

By the end of 2008, the great Financial Crisis had hit and all the banks had either given Porsche new funds or allowed the company to rollover the debt when it came due; in any case, they were no longer interested in funding a speculative scheme to corner the market for Volkswagen shares.

Porsche’s debts were coming due much sooner than they expected. And not only that — after years of consistent growth in automobile sales, Porsche’s core business of selling cars was hurt severely by the recession and unit sales dropped 27% in one year.

A financial maneuver that had been considered “brilliant” just a few months earlier was now a poor decision: Porsche was out of money. On March 24, 2009, loan payments of $13BN were due. While previously it would have been a trivial matter to refinance the amount, this time the banks weren’t interested. Moreover, Porsche owed money to 15 different banks, each of which could bankrupt the company if it so wished.

Porsche’s CFO managed to avert disaster the day before the loan was due and refinance most — but not all — of the $13BN debt into a new loan. The catch: $4.4 BN of it would be due within 6 months.

But even with most of the debt refinanced, Porsche would need additional capital to pay the part of the loan that was currently due. It just so happens that one of the board members was able to get the company an emergency infusion of almost a billion dollars from another company that he also sat on the board of. That loan would be from Volkswagen, orchestrated by their Chairman Ferdinand Piëch.

In the blink of an eye, Porsche went from predator to prey. Once on the brink of acquiring Volkswagen, Porsche now found itself borrowing a billion dollars from them just five months later.

Piëch Twists the Knife

Porsche didn’t publicly disclose the Volkswagen loan for another two months, though internally, they knew their quest to buy out Volkswagen was over. One does not simply acquire the company you are borrowing money from.

From CEO Wiedeking and CFO Härter’s perspective, this was a setback — but not necessarily a dire circumstance. Porsche was still a great car company, and they had acquired half of Volkswagen with options to acquire more of it. They might not be able to finalize the acquisition, they figured, but they still had a valuable company — as as long as they didn’t run out of money. Surely, money would be available.

The company’s immediate problem, however, was that they were about to run out of money. They now also owed money to a myriad of banks, as well as to Volkswagen, the company they had been antagonizing. But the looming $4.4 BN debt payment was a sword hanging over the company’s head, in addition to the estimated $790 MM annual interest payment.

Porsche needed help. At best, it could retain its independence if it brought in a new investor. Or instead, it could merge with Volkswagen as an equal. Still worse from Porsche’s management perspective, it could be acquired by another car company. The worst case scenario, however, was looking very likely — the hallowed sports car maker would simply run out of money and go bankrupt.

What Porsche needed was a bailout.

As many governments did during this time, the German government set up a stabilization fund to loan money to German businesses that were in need of a bailout. Porsche applied for multi-billion dollar loan, but was rejected. It couldn’t have helped that head of the Lower Saxony Government, and board member of Volkswagen, Christian Wulff, was a close ally of Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor. Wulff, who later became Germany’s president under Merkel, was said to be the one who convinced her not to repeal the Volkswagen Rule.

By the end of the spring, it appeared that a savior had emerged for Porsche, in the form of the Qatar Sovereign Wealth fund. Qatar was close to acquiring a multibillion dollar stake in the company in exchange for much needed cash to pay down the debt.

Qatar Prime Minister and Chief Executive of the investment fund at the time.

Then, the Qatar government abruptly decided not to invest in Porsche, reportedly at the urging of Lower Saxony government head Wulff and and Chancelor Merkel. Instead, they would only invest in Porsche after it had cleaned up its finances and resolved its situation with Volkswagen. (Qatar would later provide a cash infusion to the company, but only after it was too late to save an independent Porsche.)

With a healthy balance sheet of cash, the support of the German government, and Qatar’s money waiting in the wings, Volkswagen had ample funds to pick up the wounded Porsche. Moreover, Porsche owned Volkswagen nearly a billion dollars and that would be due soon.

Now was the time for Volkswagen to strike.

After publicly staying quiet on the merger for years, Piëch started rumbling about his waning confidence in the Wiedeking and the Porsche management team and their mismanagement of the company’s financance. VW’s loan would come with “strings attached.”

The “strings,” as it turned out, would be that Porsche would sell itself to Volkswagen, otherwise Volkswagen would force it to pay back the loan. By July 2009, Porsche CEO Wiedeking would resign. The $71MM severance package he received suggests this wasn’t purely voluntary, but instead was to pave the way for a Volkswagen acquisition of Porsche. Wiedeking had flown too close to the sun, and now his career at Porsche was over.

By fall of 2009, the acquisition was set. Volkswagen would acquire the Porsche automotive business for $11.3BN in cash (49% of it right away, and 51% of it later, for tax reasons). The Porsche family would retain their shares in a holding company that owned 50% of Volkswagen — but also all the Porsche debt. The Qatar fund would, however, provide capital to the Porsche holding company to help eliminate that debt.

Considering that they’d fumbled their family business, the Porsche-Piech family did pretty well for themselves. All said and done, they ended up owning approximately 32% of Volkswagen by the end of negotiations; a few years later, they bought back the shares they’d sold to Qatar.

But one member of the Porsche-Piech family did particularly well: Ferdinand Piëch. Under his lead, Volkswagen had gained control of Porsche — the company his grandfather started. His stake in Porsche became a stake in both Volkswagen and Porsche; today, it is worth many billions of dollars.

Conclusion

“You come at the king, you best not miss…”

– Omar Little, The Wire

***

So, what is to be learned from the saga of Porsche?

First, if you’re a car company, it’s probably best to focus on making cars instead of gravity-defying financial maneuvers. Wendelin Wiedeking ran Porsche brilliantly when it was just a car company. He modernized its operations, successfully added new products, and turned the company from near bankruptcy to a highly profitable enterprise. It was only when Porsche started making more money from its hedge fund-like activities than it’s automotive ones that Wiedeking got his comeuppance and was terminated (though his $71MM exit wasn’t so bad).

Second, capital has a tendency to be there when times are great, but disappears when you need it most. Different parts of the economy are highly correlated with each other. So, when your business turns sour, lots of other businesses turn sour, including the banking business. Any strategy that requires access to capital to succeed can be shakey, because capital is likely to not be available during times of duress.

Finally, if you’re going to go shoot the king, don’t miss. In order for Porsche to acquire Volkswagen, they needed to acquire 80% of the company and revoke the “Volkswagen Rule” — which allowed the local German government to block any acquisition. When the rule was not revoked, the acquisition process dragged on and sapped Porsche’s financial reserves.

All of this gave Ferdinand Piëch time to wait and see what would happen. And at the first sign that Porsche was in trouble, Piëch decisively struck and took his grandfather’s company back.

And, finally, after many decades of waiting, he became the boss of Porsche. Or rather, he became the boss of the boss of Porsche. Either way, Piëch is definitely in charge.

If you enjoyed this post, you’ might like our book → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.