One of Diederik Stapel’s retracted papers claimed to show that messy environments made people more likely to discriminate based on race

In 2011 a prominent Dutch psychologist made an enormous splash in the world of academic science, but not because he had published new, ground-breaking research. The splash came when it was revealed that the data behind some of his old ground-breaking research wasn’t quite right. In fact — a subsequent investigation found — a lot of the data behind a lot of his ground-breaking research was entirely made up. A lengthy and arduous audit ensued. To date, 54 of his published papers, spanning a decade long career, have been retracted.

This psychologist, Diederik Stapel, might have been an extreme case, but he was by no means alone in using questionable research practices. There are Stapels in other fields too, prominent scientists who were unmasked as data fabricators or falsifiers: like South Korean stem-cell researcher Hwang Woo Suk, or Harvard evolutionary biologist, Marc Hauser. And research suggests that these extreme cases are symptomatic of widespread questionable research practices in science at large, as Yudhijit Bhattacharjee wrote in a profile of Stapel in the New York Times:

[F]igures like Hwang and Hauser are not outliers so much as one end on a continuum of dishonest behaviors that extend from the cherry-picking of data to fit a chosen hypothesis — which many researchers admit is commonplace — to outright fabrication.

Research has suggested that outright fraudulent scientists tend to target journals with “high impact factors”, and certain questionable research practices are so prevalent they “may constitute the defacto scientific norm.”

It might seem as though a new retraction rocks the media every other month, these days. And the rate of retractions has gone up quite a bit: The percentage of scientific articles retracted from PubMed because of fraud has increased 10-fold since 1975, and tripled between the early 2000 to the late 2000s. The editor of the American Journal of Neuroradiology called it an “epidemic.”

On the face of it, it might look like corruption and fraud are taking over the sciences at unprecedented levels.

But according to a recent study, it’s pretty unlikely that the rate of misconduct itself has increased. The author of the study says the increased rate of retractions is due to the fact the scientific community has gotten better at detecting and combating misconduct. In other words, it may have been an epidemic all along. The malady has not spread much, but our diagnostics have improved.

If that’s the case, the author writes in the title of the paper, “growing retractions are (mostly) a good sign.”

***

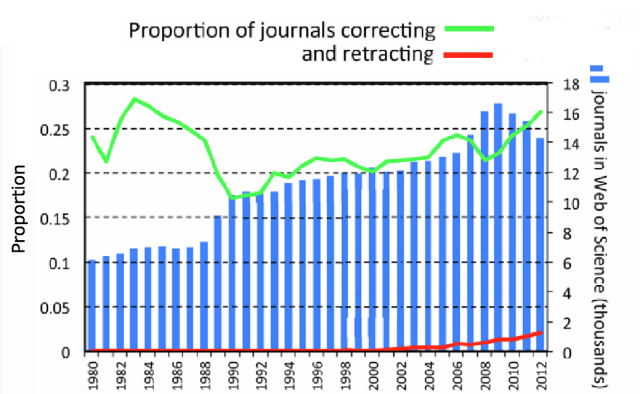

Retractions overall are up, but according to the study if we limit our analysis only to journals that issue retractions, the number of retractions per journal has not increased. We would expect them to see such an uptick if misconduct was generally on the rise. The increase in overall retractions is mostly because a higher percentage of journals have begun issuing retractions.

Blue bars indicate the total number of journals in Web of Science, by year; green tracks the percentage of those that issue errata; red tracks the percentage of those that issue retractions; Source: Fanelli

One reason why it’s taken a while for journals to begin issuing retractions, could be that they had to develop the necessary guidelines for defining, detecting, and dealing with “misconduct”. Technology has recently made plagiarism affordable and easy to detect. And most scientific journals and countries still don’t have clear frameworks to deal with misconduct, but as the author points out, they’re slowly but surely developing them. As the author writes out, “systems to fight scientific misconduct are recent, and growing.”

One such system is the US Office of Research Integrity. More evidence that the scientific community is being more proactive at sniffing out misconduct is that the number of queries and allegations made to the US Office of Research Integrity nearly doubled between 1994 and 2011. This probably in no small part to the rise of the Internet as a tool for review. And — as further evidence that misconduct is not on the rise — the proportion of the Office’s investigations that result in findings of misconduct has not increased.

Retractions: “Mostly” a Good Thing

As the author of the paper writes in the discussion section:

Data from the WoS database and the ORI offer strong evidence that researchers and journal editors have become more aware of and more proactive about scientific misconduct, and provide no evidence that recorded cases of fraud are increasing, at least amongst US federally funded research. The recent rise in retractions, therefore, is most plausibly the effect of growing scientific integrity, rather than growing scientific misconduct.

So the next time you hear of a big scientific retraction, take hope: it may be that the system is getting stronger. Another study found that editors are retracting articles significantly faster now, than in the past. We might be working our way towards a future in which fraudsters like Stapel won’t build up such massive bodies of literature before being unmasked. Their first or second will be caught, before they’ve done too much damage.

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list