Photo credit: Quinn Dombrowski

![]()

In the summer of 2013, Drew Brees, the six-foot, 200-pound New Orleans Saints quarterback who regularly evades blitzing linemen, was taken down by a Tweet. A gossip site called The Dirty posted a picture of the millionaire’s $74.41 receipt from the Del Mar Rendezvous restaurant in San Diego. The receipt showed that Brees tipped $3, and The Dirty titled the blog post “New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees is a Cheap Bastard.”

Brees faced populist rage on social media and in the press — until he explained that he gave only a three dollar tip because he ordered takeout. “Had we sat down,” Brees tweeted, “it would have been 20% plus.”

Almost immediately, Brees received a full public pardon. Commenters noted his actions were appropriate — one supporter wrote, “Receipts for takeout orders shouldn’t even HAVE a line for a tip,” — and the manager of Del Mar Rendezvous apologized to Brees and donated $888 to a local charity supported by the quarterback.

Tipping is, in theory, a voluntary act. Yet Americans feel strongly that tipping waiters and waitresses anything under 15% is perniciously cheap, and most people seem equally certain that tipping on takeout orders is unnecessary.

No one is more aware of this disparity than restaurant workers like Samantha, who works the register at an upscale soup, salad, and sandwich spot in San Francisco. When she worked as a hostess at a sit-down restaurant, she says, she would earn $100 in tips in just 3 hours. Now, after an eight hour shift at the sandwich shop, she earns an average of $20 in tips.

The result of people not tipping on takeout, according to Samantha, is that workers like her “get kind of screwed.” So should we all be tipping on takeout?

Who Tips on Takeout?

Photo credit: Ginny

Tipping on takeout is common but not the norm. Samantha reports that around 25% of her takeout customers tip, while a server at another lunch spot — where Priceonomics staff often pick up lunch — says that over 15% of takeout customers tip. Employees at several ethnic, sit-down restaurants in San Francisco tell us that under 20% of takeout customers tip.

It’s nearly impossible to say how often people tip on takeout in different parts of the country and at different types of restaurants, but 20% or less seems typical. Steve Dublanica, the author of Keep the Change: A Clueless Tipper’s Quest to Become the Guru of the Gratuity, worked in upscale New York restaurants and says that “80 percent of the time, people did not tip on takeout orders.” In his apology to Drew Brees, the manager of San Diego’s Del Mar Rendezvous wrote that “takeout orders do not usually garner a tip at our restaurant.”

Opinions vary among servers on the tipping question. In response to the Drew Brees “scandal,” a number of servers said Brees’ $3 (four percent) tip was “the norm” or “generous,” and that they did not expect a tip on takeout orders. Jane of Basil Canteen, an upscale Thai restaurant in San Francisco, told us “it’s hard to say” whether people should tip on takeout and called it a “personal opinion.” Then she added that she “thinks people should tip [to] show kindness.” Samantha more readily expressed that yes, people should tip.

In other words, no one agrees. Not even servers who hand out takeout food.

Why do we tip?

The confusion over tipping on takeout has a clear root cause: no one knows why we tip in restaurants, which makes it impossible to say whether takeout orders merit a tip.

Do we tip to ensure great service? If so, tips fail as an incentive system. Jay Porter, who ran and owned a San Diego restaurant that banned tipping in favor of a fixed service charge, has written, in a series of blog posts about his experience, that many waiters don’t check how much each table tips — and when a server does get a small tip, he often assumes the diners were cheap. This is a reasonable assumption. Americans tend to tip a fixed percentage of their bill regardless of service: research out of Cornell suggests that judgments of a waiters’ service account for under 2% of the variation in tips. If tipping is so important, it’s also unclear why restaurants automatically add gratuity for large parties.

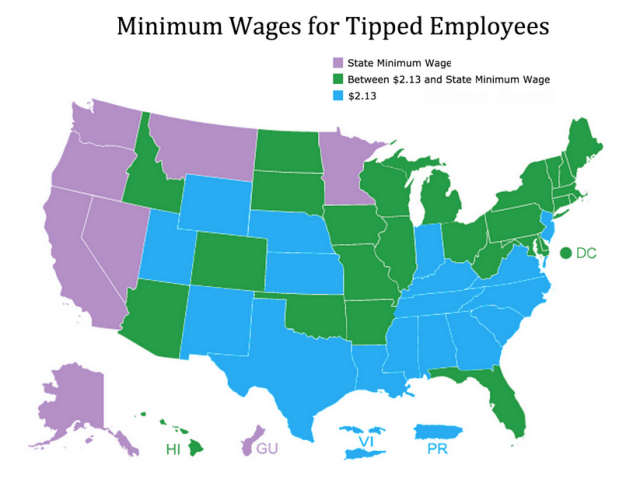

Do we tip because American federal law allows restaurants to pay waiters under minimum wage — as low as $2.13 an hour — so long as they make minimum wage after tips? After all, if we didn’t tip, many restaurants’ entire compensation system would break down. But restaurants can pay servers as low as $2.13 per hour in only 17 states. Many state laws mandate a higher wage, and 7 states require that servers make the state’s minimum wage before tips — which can make for large disparities in waiters’ pay across state lines.

Map from U.S. Department of Labor. In blue states and territories, tipped employees can be paid as low as the federal tipped minimum wage of $2.13 an hour. Purple states require employers to pay workers full state minimum wage before tips. Green states require employers to pay workers above federal tipped minimum wage.

Is a tip a “gift” that, as Aeon writer Julian Baggini argues in a recent article, “humanizes rather than commodifies the experience of eating”? Restaurant owners like to think of their establishments as their homes and customers as guests, so perhaps a tip is a gift given in gratitude for a great meal. Yet calculating (an expected) 15% or 20% of our bill at the end of a meal seems like a strange way to humanize our dining experience, and the tip is hardly an optional gift in states where waiters make $2.13 an hour.

Or are tips compensation specifically for the service of a waiter taking our order, bringing out dishes, and doing everything involved in waiting a table? This would explain why the price of a fried rice dish is the same in a restaurant as on its takeout menu. Yet this explanation fails to account for people who tip less when their steak is burnt — something the waiter cannot control — as well as the fact that waiters, cooks, and other staff often split tips.

This practice of waiters sharing tips with chefs is actually both widespread and illegal under federal law. Tips legally belong to the employees who receive them, and employers can only force waiters to share tips with bartenders, hostesses, and other employees who directly interact with customers. But as restaurants have slim profit margins, sharing tips is often the only way to make sure all the staff, chefs and dishwashers included, make above minimum wage.

Jay Porter points out that restaurants can do this legally by partially or fully replacing tips with a service charge. In addition, states which allow waiters to make below minimum wage (pre-tip) offer restaurant owners more ability to dole out money evenly among the staff.

But illegal tip pooling is common. Assaf Lichtash of Pershing Square Law Firm, which specializes in employment law, notes that restaurant owners often divide money in a way that makes sense to them, and many are immigrants who bring their own understanding of what’s fair. So whether formally (but illegally) enforced by managers and owners, or done informally among staff, tips are often split with cooks, dishwashers, and other employees who don’t serve customers directly.

As a result, the notion that tips are explicit compensation for the act of waiting tables — and therefore irrelevant to takeout orders — does not match the reality of the restaurant business.

No Easy Answer

Photo Credit: Doug_r

Since no one knows why the hell we tip, no one can say with confidence whether we should tip on takeout. Any comparisons or arguments people make inevitably run into contradictory tipping practices, or are not universally applicable.

If you compare takeout to delivery, it makes no sense to tip. We tip the delivery guy for schlepping pizza to our house, so why tip when we drive to Uno’s and pick up a deep dish? On the other hand, if we tip bartenders for handing over a bottle of Budweiser, why don’t we tip someone who hands us pad thai to-go?

Since restaurants charge the same for a takeout dish as the same dish ordered in the restaurant, it would make sense for the tip to be the extra service charge for dining in. Chefs around the country, however, commonly — if illegally — rely on tips. From these chefs’ perspective, nothing changes if you order takeout, yet they don’t get tipped. When we asked Samantha if she thought customers should tip on takeout where she worked, she pointed toward the kitchen and said, “I don’t know about me, but they should get tipped.”

Of course, you could rightly retort that it’s illegal for chefs to receive tips. Yet in many restaurants, the employees that hand out takeout also run around waiting tables, which means they miss out on tips by taking care of your takeout. And when you think about it, the work performed by employees who manage takeout orders — explaining the menu, getting your order in correctly, packaging the order and making sure nothing is missing, handling payment — sounds a lot like the service a waiter performs.

So, should you tip on takeout? No one can answer that question, because it is like asking whether you should tip 12% or 15% or 20%, or asking how much you should deduct from a tip for poor service. Everyone has his or her own idea about what’s right, and since modern tipping is the bastard child of European aristocrats throwing spare change at servants to keep them fawningly dependent (yes, that is the origin of American tipping), there’s no logic to the system.

When articles about tipping — and especially tipping on takeout — seek authoritative answers, they ask “etiquette experts.” Usually this means Peter Post, the managing director of the Emily Post Institute and the great-grandchild of Emily Post, the author of Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics, and at Home. Post’s biographer described her as a “daughter of the gilded age.” A New York Times journalist noted that Emily Post grew up “in a world of grand estates” and shared her knowledge of that world’s customs and rituals — elbows on the dinner table are fine; young women need a chaperone — with America’s immigrants and middle class.

As for modern tipping etiquette, according to Peter Post and his institute, there is “no obligation” to tip on takeout, but one should tip 10% for “extra service (curb delivery) or a large, complicated order.”

So how did Peter Post and company come up with this answer? The institute asks that people refer to its articles rather than call in with etiquette questions. We did, and we found no evidence that anyone at the institute grappled with differing state laws on tip sharing and minimum wage or any other issues. Here is Post explaining to the press why tipping on takeout is unnecessary:

“There‘s no need to leave a tip when picking up take-out. This is no different than going to the auto parts store and picking up a car part that you’ve ordered. You just wouldn’t tip the guy at the auto parts store.”

Post’s logic is indecipherable from any Internet commenter blurting out an opinion. If Post has any qualifications to make him an expert on tipping beyond his relation to a famous etiquette author — like having researched tipping or surveyed restaurant owners — the institute is not displaying them.

Tipping may seem like a small thing — a few dollars here, a few dollars there. But it adds up to a huge deal for millions of workers and a substantial chunk of the enormous restaurant industry’s revenue. In Keep the Change, Steve Dublanica’s back of the envelope calculation (using 2009 figures) estimates that tipped workers earn between $53 billion and $67 billion in gratuities every year. Peter Post’s tipping philosophy may be fine, but it’s definitely not well thought out enough for so impactful a practice.

Answering this question of tipping on takeout is difficult. Circumstances differ from restaurant to restaurant, tipping as a system has no internal logic, and even servers disagree about tipping on to-go orders.

Yet in this author’s experience, restaurant workers express support for tipping much more readily than the average customer. At one lunch spot near the Priceonomics office, a server said, “I tip wherever I go, because I know how hard the work is.” In contrast, the etiquette experts who say tipping on takeout is unnecessary are people like Peter Post, who is the author of Playing Through: A Guide to the Unwritten Rules of Golf. That seems like an argument for erring on the side of generosity.

![]()

Want to write for Priceonomics? We are looking for freelance contributors.