Sometimes, when neuroscientists make art, they make giant interactive glowing metal brains

Is it good for engineers and scientists to have artistic pursuits? Surely they and the world would be better off if neuroscientists focused more on neuroscience, not hooking up an EEG to a music visualizer? Is there any point in a quantum physicist writing operas?

It turns out that even for individuals, the interaction between science and art is actually pretty complicated. It seems avocational creativity discoveries of professional scientists go hand in hand: the more accomplished a scientist is, the more likely they are to have an artistic hobby.

The average scientist is not statistically more likely than a member of the general public to have an artistic or crafty hobby. But members of the National Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society — elite societies of scientists, membership in which is based on professional accomplishments and discoveries — are 1.7 and 1.9 times more likely to have an artistic or crafty hobby than the average scientist is. And Nobel prize winning scientists are 2.85 times more likely than the average scientist to have an artistic or crafty hobby.

The Correlation Between Arts and Crafts and a Nobel Prize

Rosie Cima, Priceonomics; data Root-Berstein et al

This analysis, which comes from a paper out of Michigan State University, depends on data gathered from several sources. The data about the hobbies of members of the Royal Society, National Academy, and of Nobel Prize winners was gathered from biographies, memoirs, obituaries, and other research. A scientist was counted as having an artistic or crafty hobby, “if they described themselves or were described by biographers as being a painter, photographer, actor, performer, composer, poet, dancers, craftsman, glassblower, and so on after entering college; if they took lessons in an art or craft as an adult; or if there was direct evidence of artwork, photographs, sculptures, compositions, poems, performances, and so on.”

“People who were vaguely described in terms such as “having an artistic personality” or “having an avid interest in music” were not counted, and separate codings were made for evidence of collecting art, music, and so on, but were not included in the data analyzed in this article.”

The data about the general population of scientists comes from a survey of members of the Sigma Xi society. Sigma Xi is an honors society, founded in 1886, of which any working scientist or engineer can become a member.

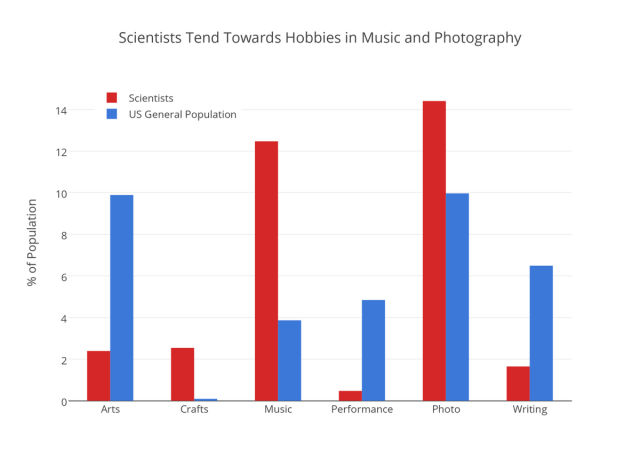

The paper’s authors also compared these values to the rates of artistic or crafty hobbies among the U.S. general population. The “average scientist” as measured by the Sigma Xi survey wasn’t any more likely than the general population to have an artistic or crafty hobby. But they were much more likely to be a musician or a photographer than the general population, and also less likely to be writers, visual artists, or performance or theater artists.

Rosie Cima, Priceonomics; data Root-Berstein et al

That distribution is different among more accomplished scientists. Nobel winners, for example, are 12 times more likely to be writers than scientists in general are.

Rosie Cima, Priceonomics; data Root-Berstein et al

The Benefits of Arts and Crafts

If you view artistic talent and scientific acumen as isolated from each other, then these polymaths are very low probability events. Not only is it unlikely that one person is going to be blessed with both artistic talent and scientific talent, but it also seems that the time trade-off alone causes a paradox. Hobbies like woodworking and music take time, time that could otherwise be spent in the lab. Why would “distractions” like this correlate to greater accomplishment?

It appears that artistic development and scientific productivity are closely related — experience in the arts enriches ones skills in the sciences. The authors’ theory is that, “there exist functional connections between scientific talent and arts, crafts, and communications talents so that inheriting or developing one fosters the other.”

Ramón y Cajal sketch of neurons

As Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the Spanish father of neuroscience — also an accomplished illustrator and draftsman — wrote, “To him who observes [scientists with artistic hobbies] from afar, it appears as though they are scattering and dissipating their energies, while in reality, they are channeling and strengthening them…The investigator would possess something of this happy combination of attributes: an artistic temperament which impels him to search for, and have the admiration of, the number, beauty, and harmony of things.”

A recent paper, “Dual thinking for scientists,” in Ecology and Society suggests that artistic engagement develops talents necessary to being a more creative scientist. The paper argues that science as it is typically studied, practiced and taught focuses on more on linear, logical thinking. Art, on the other hand, thrives on other systems — kinetic and associative thinking.

“I have slowly come to realize that the analytic, quantitative approach I had been taught to regard as the only respectable one for a scientist is insufficient,” British metallurgist Cyril Stanley Smith once wrote. “The richest aspects of any large and complicated system arise from factors that cannot be measured easily, if at all. For these, the artist’s approach, uncertain though it inevitably is, seems to find and convey more meaning.”

Artists get a lot of practice letting their mind “wander.” And some of the great scientists of history employed techniques very similar to those used by the world’s greatest artists. Charles Darwin had a particular favorite meditative walk, and Benjamin Franklin gained his best insights in the bath. And consider the great insight of the German chemist August Kekulé:

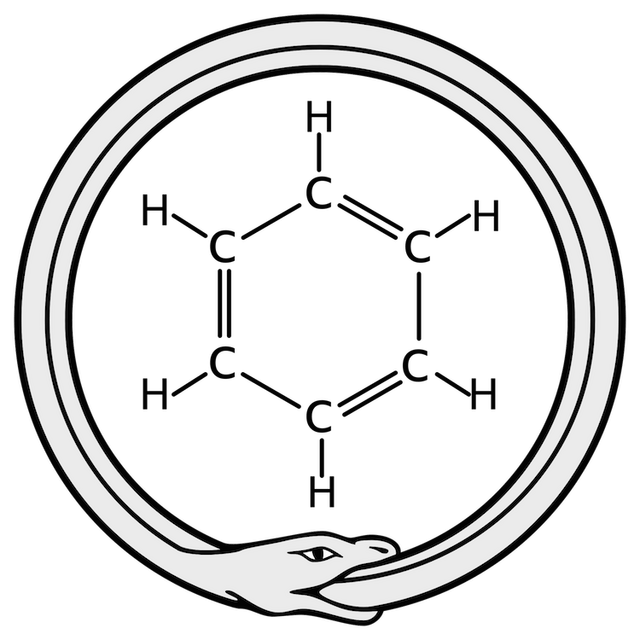

“[…] after thinking intensely about the seemingly insolvable question of what the structure of a benzene molecule could be, [Kekulé] fell asleep in his chair at the fire place and woke up with the revolutionary idea of a circular structure linked to a dreamy vision of a snake biting its own tail.”

Benzene ouroboros, Haltopub

Salvador Dali would dream in his chair as part of his work routine. The authors of the paper “Dual thinking for scientists” suggest controlled risk-taking, and artistic hobbies, and so called “mind-wandering” into future scientific education.

“Deliberate effort is needed to counteract our systematic bias,” the authors write. “Such activities may be looked upon as procrastination rather than work.”

For our next post, we’ll tell the story of a man who conned a game show in the 1980s. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

***

This post was written by Rosie Cima. You can follow her on Twitter here