Photo by Adam Valstar on Unsplash

“You don’t have to be smart, athletic, rich, or clever to appreciate the Slinky. It’s a toy for regular people.”

— Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, 1993

![]()

It has been said by industry executives that only one in a thousand toys makes it to the big time. Of those that persevere, most live and die on the pulse of advertising and product release cycles, only to fade into obscurity after a few years of success.

The Slinky is not most toys: in its 70 years on the market, it has sold more than 300 million units. The Slinky seems to be oddly immortal — and this is confusing. After all, it’s essentially just a glorified spring. It does nothing particularly extraordinary or special. More often than not, it works itself into an impossibly tangled mess. Yet it is utterly simple, and this simplicity has made it iconic.

To counterbalance its simplicity, the Slinky has an utterly complex backstory. The toy has dealt with a slew of uncanny circumstances — an inventor who fled to South America to join a religious cult, a seven-figure debt, a mind-boggling reemergence under unlikely leadership — and has somehow managed to prevail with very little redesign.

Springing into Action

Born January 1, 1914, in Delaware, Richard Thompson James was a curious child. When the United States entered a brief economic depression in the early 1920s, he often had to get creative in his endeavors to keep himself entertained: armed with a vast imagination, springs and pieces of glass became captivating toys.

As recounted by his brother, Samuel, in a 1976 interview with the Delaware County Daily Times, James had an indeterminable spirit to “get things done,” and to make money:

“I remember a Sunday morning hike when Richard found an old abandoned 1923 Buick car. He was only 13 years old at the time but he was determined to fix up the car. It was full of wild cherry seeds and mice. It was a mess. But he got it to run and he sold it for $25.”

As a young man, James became interested in how things were built; by the late 1930s, he’d graduated from Pennsylvania State University with a degree in mechanical engineering, and entered the workforce as a naval engineer. After the United States became involved in World War II, James accrued a desk job at a William Cramp & Sons shipyard in Philadelphia, where he was tasked with building tools for submarines and iron ships.

It was here, on a muggy day in 1943, that he inadvertently invented one of the hottest toys of the 20th century.

In the midst of developing a system that could “support and stabilize sensitive instruments aboard ships in rough seas,” James swiveled around and clumsily knocked a tin of spare parts from an overhead shelf. When he bent to retrieve the items, he amusedly watched as a lone spring wobbled in “steps” across the desk, down a stack of books, and onto the floor. For the rest of the day, James’ curiosity was unflinching, and he returned home later that evening still reeling with joy.

“I think if I got the right property of steel and the right tension,” he told his wife, “I could make it walk!”

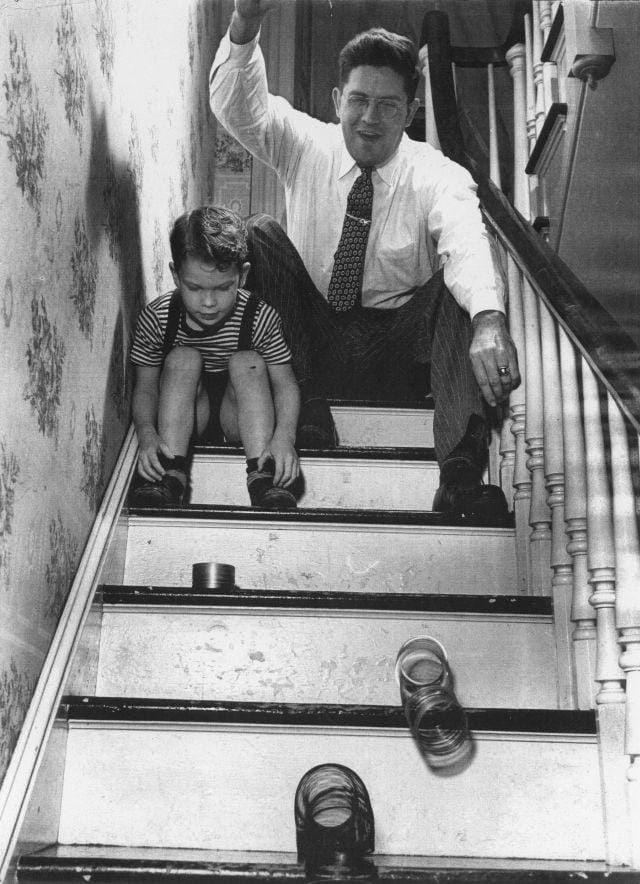

James with his son, 1940s

For the entirety of a year, he tinkered with various wire types and tensions in his free time. Eventually, after settling on just the right combination — a high carbon steel wire 0.0575 inches in diameter — his “walking” spring appeared to move effortlessly down staircases.

Though mysteriously entertaining, the spring relied on a simple law of physics, Hooke’s Law, which stipulates that restoring force is directly proportional to the displacement. When the spring began its downward journey, potential energy was converted into kinetic energy, and it would continue hopping over itself until reaching a flat surface.

Armed with his new invention, James engaged his neighbors for a little product testing. To the scientifically-uninformed children on James’ street, the spring was magical. When James saw their captivation, he knew it had potential as a toy.

Next, he turned to his wife, Betty, who was skeptical of the spring toy, and asked her to come up with a name for it. She poured through the dictionary for several weeks before finding just the right word — slinky, which was not only a widely-used synonym for “sleek and graceful,” but seemed to her like a verbalization of the sound the toy made.

Early Success

Images from James’ patent, filed in August 1946 and approved January 1947

Soon, James had perfected his newly-termed Slinky, and was ready to unveil it to consumers. After securing a $500 loan from an awestruck friend, he formed an LLC — James Spring and Wire Company — and brought his prototype, along with several thousand yards of wire, to his local machine shop. Here, 400 Slinky units were produced to James’ specifications: each was 2.5 inches tall, contained 80 feet of “high-grade blue-black Swedish steel wire” wrapped into 98 coils, and came packaged in simple parchment paper.

The contraption was so alarmingly plain (it was just a coiled wire with no frills, after all), that toy stores showed complete disinterest in stocking it. Upon seeing the toy, one frustrated storekeeper voiced his opinion:

“This is the atomic age in toys. Kids want big, bright, fancy things with lots of color and lights. An old beat up spring! We couldn’t give that thing away if it played God Bless America and picked the daily double at Hialeah as it walked down the steps.”

But James wasn’t deterred. Finally, after much negotiation, Gimbels, a department store in Philadelphia, agreed to include the units as part of its Christmas display; in November 1945, the Slinky debuted in the store’s toy section.

James and his wife eagerly awaited their first sale — but days turned to weeks, and the Slinkys sat untouched. Perched between big-eyed plush dolls and shiny electric train sets, the boring springs stood no chance.

Finally, James decided he’d take matters into his own hands. “Come meet me at Gimbels in a few hours,” he told his wife, and marched out the door. Once there, he proceeded to set up his own display, sit down with children, and perform interactive shows with his invention. By the time she arrived 90 minutes later, James had sold all 400 units at $1 a piece, and there was a line down the block demanding more. By Christmas, James had sold 20,000 Slinkys.

Suddenly, the little Slinky was the talk of the town.

When James and his wife debuted the contraption the following year at the American Toy Fair in New York, the reception was incredible: after viewing James’ grassroots sales pitch, hundreds of toy stores and retail chains clamored to place their orders. By the end of 1947, the Slinky was a national phenomenon — and not just as a toy. In an archived NYTarticle, one fashionista revealed the must-have Christmas decoration of the year: a Slinky “dipped in gold paint and sparkling glitter.” A glamorous, sleek item, the Slinky had finally lived up to its name.

The Slinky Goes Big Time

As the orders and demand grew, Richard James soon realized it was time to ditch his local machine shop. He was, after all, a mechanical engineer, and was perfectly capable of inventing his own machine.

So, he opened up a machine shop in Albany, New York and got to work. His resulting device — a mountainous hunk a steel the size of a grizzly bear — was relatively simple: wire was fed into a slot, smashed, then very quickly coiled around thick metal bars.

Whereas the machine shop once took a few minutes to craft each Slinky, James’ new machine could roll one out in less than five seconds. Needless to say, production was vastly improved. James also revamped his packaging, ditching the yellow parchment paper for a clean-cut black box that read “Slinky: the famous walking spring toy.”

With these advancements, James sold more than 100 million Slinky units in the first two years of production; as he kept the price of the toy at $1, he raked in the modern equivalent of $1 billion in revenue.

This immense success allowed James to roll out various other Slinky toys throughout the 1950s — the Slinky train (Loco), the Slinky worm (Suzie), and the Slinky Crazy Eyes (glasses with Slinky-fitted eyeballs) — many of which were built from ideas coined by customers and children. In 1952, a Slinky fan named Helen Malsed sent the company a drawing of her idea for an animal toy; the result, the “Slinky Dog,” went on to sell millions of units (Malsed received a royalty of $65,000 every year for the next 17 years).

And that was just the beginning: the patent James had filed in 1947 for his specialized spring was in high demand by not just toy manufacturers, but everyone from government agencies to farmers — and he made untold millions by sub-licensing its use. By the end of the decade, the toys had been integrated as light fixtures, gutter protectors, wave motion coils, therapeutic devices, and antennas.

Slinky’s Inventor Joins a “Cult”

But beneath the aura of Richard James’ immense success, there was some immensely weird stuff going on in his life

By the mid-1950s, James and his wife, Betty, had started a family. As they spent more time at home — a sprawling 12-acre, 31-bedroom estate in Bryn Mawr, one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest suburbs — James grew increasingly isolated from society and his duties as a father.

James’ troubles began when Betty found out he was a philanderer — he’d been “fooling around” with other women behind her back. Though Betty stayed with him for the benefit of the couple’s six young children, this revelation caused intense unrest in the household. Subsequently, James began spending more time at church, in the confession booth. “He was a charismatic man who had gotten used to being a big shot,” Betty told a reporter, “and he liked the attention he got while confessing his sins.”

But there was another reason James was distant: while the Slinky had made him millions, he’d secretly given away most of his fortune to ultra-dogmatic, evangelical religious groups (side note: if you bought a Slinky pre-1960, this is where your money went). In fact, James had “donated” so much money that he’d run his family seven-figures into debt. What’s worse, the Slinky’s trendiness began to lose steam by the end of the 1950s, and business wasn’t so hot. On paper, James was in serious financial trouble.

Once obsessed with obtaining wealth, he’d become wholly disinterested with money now that he had it. “Pop used to say, ‘Money means nothing to me,’ and he would tear it up,” recalls his son, Tom. “I’d find it and tape it back together.”

Then, in February 1960, James made an unexpected and dramatic exit.

With little explanation, he bought a one-way ticket to rural Bolivia, and joined what his wife called “an evangelical Christian cult” somewhere deep in the wilderness.By July, he’d severed all ties and disappeared.

Just before leaving, he’d presented Betty with a choice: she could liquidate the company, or assume sole ownership. She chose the latter.

The Second Coming of the Slinky

Betty James began her journey as Slinky’s sole proprietor at a severe disadvantage: the toy was on a decline, the LLC was million of dollars in debt, and she’d been left to raise six children as a single mother.

Strong-willed and resilient, Betty was up for the challenge.

Her husband had, at some point during the company’s success, diverted nearly all of its profits to various religious sects, leaving it in substantial debt. Betty’s first plan of action, to defer the sea of creditors awaiting payments, was successful — “a miracle,” she later said. Then, she went about re-branding the toy.

In 1962, she commissioned three musicians to write a jingle for Slinky, and set in place an aggressive television advertising campaign. The jingle, which famously proclaimed “Everyone wants a Slinky; You want to get a Slinky,” worked: it not only rejuvenated interest in the toy, but went on to become the longest-running jingle in the history of television advertising.

As sales slowly began to creep back up, Betty made another crucial business maneuver, moving the Slinky production facility to a cheaper, more convenient location in Philadelphia. For a period of several years, she fully invested herself in the company’s operations: with her children under the watch of a caregiver each Thursday through Sunday, she spent late nights strategizing and trying to rebuild the family’s future.

The Slinky saw a colorful revival with the introduction of a rainbow-colored plastic version in the early 1970s. When a Minnesotan plastic worker came up with the concept, he could think of only one person capable of making it successful: Betty James. She took the man’s prototype, developed it into a member of the Slinky family, and marketed it as a “safer, less tangle-prone alternative” to the company’s metal toys. They sold like hotcakes.

In 1974, Betty received word that her ex-husband, Slinky’s inventor and one-time CEO, had passed away in Bolivia, at the age of 56. Since James’ departure in 1960, Betty had completely turned the company around: sales were soaring, debts were paid off, and the Slinky was cool again. Against all odds, she’d proven herself to be a more formidable business-person than her predecessor.

![]()

By the time Betty James sold James Industries to toy manufacturer Poof Products, Inc. for “a boatload of money” in 1998, she’d sold more than 300 million of its flagship product, the Slinky.

She’d taken an ailing company and given it a second life, not only providing for her own family, but the families of the close-knit 120-person team she’d built. She’d skillfully navigated the old-school toy through five decades of flashy gadgets.She’d expanded the company’s product line, and even cracked a deal with Pixar to have the Slinky Dog make an appearance in Toy Story — a move that had doubled the toy’s sales. She’d produced more than 3,000,000 miles worth of Slinkys — enough to circumvent the Earth 121 times.

And she’d done it all by trumpeting the value of simplicity.

“The simplicity of the Slinky,” she told an AP reporter in 1995, “is what made it so successful”: simplicity in design, simplicity in advertising, and, most importantly, simplicity in pricing.

In 1945, the Slinky sold for $1.00; by the late 90s, the same model sold for just 89 cents more. “So many children can’t have expensive toys, and I feel a real obligation to them,” she reiterated in the New York Times. “I’m appalled when I go Christmas shopping and [see] $60 to $80 toys.”

Though she passed away at the age of 90 in 2008, Betty James’ efforts were recognized with an induction into the Toy Industry Association’s Hall of Fame. “James combined a profound business savvy, sharp instinct for quality manufacturing, and true heart,” reads her inscription. “Her commitment and perseverance have allowed children around the world the opportunity to relish the ingenuity and pure fun of a Slinky.”

***

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.