Skittish, shy, and perennially lackadaisical, cats don’t seem particularly suited for warfare. Yet, as far back as 9,500 years ago (shortly after their domestication), they were instituted as pint-sized warriors in naval ships and rat-infested trenches. During World War I, the British army employed nearly 500,000 of the felines to fend off unwanted critters on land and at sea; nearly every World War II vessel had at least one aboard at all times.

But in this boundless expanse of cats, one stood out for his outstanding valor. His efforts for Britain’s Royal Navy during World War II — first surviving a brutal attack that killed his caretaker, then proceeding to annihilate rats and raise the morale of his crew — made him a national hero and earned him the prestigious Dickin Medal. To this day, he is the only cat to ever receive the award.

This is the story of how Simon — the bravest cat in history — came, pawed, and conquered.

The Medal of Honor for Animals

Before we jump into Simon’s harrowing tale, let’s first clarify what qualifies an animal as “brave.”

Since 1861, only 3,469 US soldiers have been bequeathed the Medal of Honor, the country’s highest military recognition. Britain’s equivalent, the Victoria Cross, is even more sparsely given out (just 1,354 in 154 years). The Dickin Medal, the UK-issued equivalent for our furry friends, is the highest military honor an animal can receive, and has only been awarded 65 times.

In the early 1900s, the medal’s namesake, Maria Dickin, a social reformer in London, began to notice that a large number of the city’s animals were living in appalling conditions. One night, while nursing her own sick puppy, she had an epiphany: It was her destiny to provide animals with free health care. In an archived BBC interview, she recalls the moment she realized this for the first time:

“I had her in my arms in the middle of the night, and she was looking so pathetically gloomy. I just put my face down on her head and sang her a song of weariness and pain. In my mind, I could see suffering animals all over the world without anyone to help them. ‘This can’t go on,’ I told myself — someone must do something about this. I learned in life that if you want anything done, you do it yourself!”

Dickin’s plan — to provide care for the “sick and injured animals of the poor” — was initially scoffed at by veterinarians, and she was cast off as a batty old woman. But in 1917, with a small group of supporters, she opened her first clinic in a cellar and began to train her own vets. By the 1940s, her institution, People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA), had become one of Britain’s largest animal care facilities.

Around this time, Dickin also mobilized a plan to recognize the efforts of animals (mainly pigeons, horses, and dogs) being used in war — partly out of love for the creatures, but also as a PR stunt to raise awareness of the PDSA. In 1943, the foundation instituted the Dickin Medal, an award to acknowledge animals’ “conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving [in war].” Since then, the tiny bronze medallion, which reads “For Gallantry” and “We Also Serve,” has only been awarded prudently:

Recipients of the Dickin Medal (1943-Present)

In the medal’s first six years (1943-1949), an unlikely fowl reigned supreme: 32 of 54 medals — nearly 60% — were bestowed on pigeons. With a bit of context, this isn’t surprising.

Over the course of both world wars, nearly 800,000 pigeons were used to transmit messages — sometimes flying up to 600 miles to complete the task. Similarly, they were stocked in nearly every British aircraft; if the plane was hit, the birds would be released with location information, and would know exactly where to fly to ensure a rescue.

Winky, one of the first three pigeons to be awarded the Dickin Medal, served this purpose: When a British bomber crashed in the North Sea in 1942, the crew, without radio transmission, struggled to stay alive in freezing waters; as a last effort, they released the “blue-chequered hen,” who ended up flying 120 miles home to deliver the crew’s location. WIlliam of Orange, a “confident, noble budgie,” flew 250 miles to deliver a message that saved 2,000 lives in the Battle of Arnhem, and later went on to become “the grandfather to many great racing pigeons.” Another “grizzle-colored cock,” Gustav, delivered the very first report of D-Day to the British mainland in 1944 — a feat which required him to fly 150 miles through 30 mile-per-hour headwinds and a tumultuous storm.

While fearless pigeons commanded early respect from the PDSA, 18 dogs were also recognized for their efforts to find soldiers buried in rubble, locate mines, and serve as morale boosters for prisoners of war. Rip, a mixed-breed terrier, saved over 100 lives during World War II air raids; Ricky, an Old English Sheepdog, cleared dozens of landmines in the Nederweert canals — even after being gravely injured by one.

Four horses — Olga, Upstart, Regal, and Warrior — have also been awarded the Dickin Medal: Two for controlling traffic during World War II, and two for remaining calm during crises. Most nobly, Olga survived a railway bomb blast that killed four soldiers and destroyed half of her stable, yet continued to dutifully serve her post.

But in the great, vast annals of military history, only one cat has ever earned the award.

Simon’s Story

In the Spring of 1948, while walking along a busy naval shipyard on Stonecutter’s Island in Hong Kong, British seaman George Hickinbottom spotted a tiny, “undernourished and feeble” cat making his way across the docks.

The soldier, just 17 at the time, had been stationed in China as a crewmember of HMS Amethyst, a frigate sent to protect British troops in the country. China, embroiled in a civil war between the Republic of China and the Communist Party, was still engaged in hostile warfare.

Hickinbottom took a liking to the kitten, scooped him up, and “smuggled” him into the Amethyst’s cabin under his tunic. At the time, it was common for war ships to house cats, as they were adept at catching and eradicating mice — creatures that spread disease, damaged ropes and woodwork, and muddled in the crew’s food supply. Cats were also believed by many seamen to possess “miraculous weather-detecting powers:” If a cat licked its fur, it supposedly indicated a hail storm; a sneeze meant rain, and “friskiness” was an omen of high winds. Most sea cats, according to historical accounts, were kept on board both as a good omen and for practical purposes.

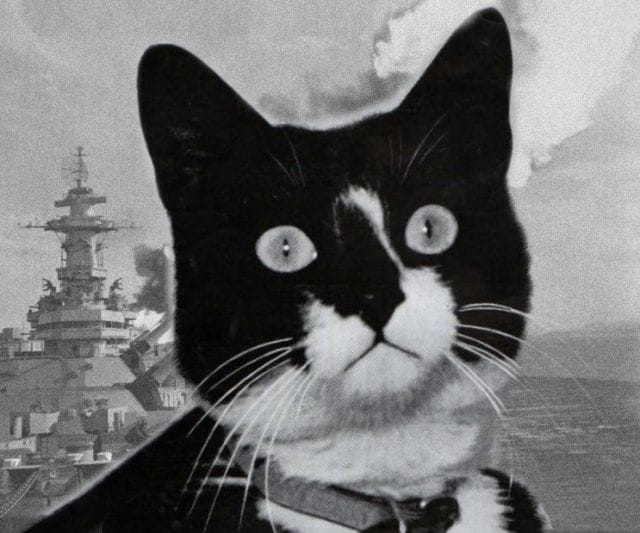

Hickinbottom soon declared his new pet “Simon the captain’s cat” and put the feline to work. Almost instantly, the cat “gained a reputation for cheekiness, leaving presents of dead rats in sailors’ beds, and sleeping in the captain’s cap.” Simon grew to a fairly average-sized “moggy” (mixed breed); his fur — all black with a white bib and white paws — made him instantly recognizable to other crews.

For a year, Simon trotted about the ship, napping in the sun and revelling in his newfound attention. He quickly earned repute for his “party tricks” — one of which was “fishing ice cubes out of a jug of water with his paw” — and was “spoiled” by the ship’s enamored crew. When Bernard Skinner joined the ship as its Lieutenant Commander, he developed a fondness for the cat, and kept him close in his quarters during the day. Simon even earned the admiration of Peggy, a ship’s dog: As one sailor on the Amethyst later told the BBC, “the two were equals — friends even.” He elaborated on the importance of these animals:

“We had Simon on board because people liked him, he kept people company. It’s the same reason you have one at home: Hearing a cat purr, and the like — its very comforting to people. It’s someone you can talk to. If you’re in a stressful situation, an animal is attractive.”

The Amethyst’s crew with Simon (look closely), and Peggy (the ship’s dog)

The “stressful situation” came soon enough. On April 20, 1949 (about a year into Simon’s ship duty), the HMS Amethyst made its way up the Yangtze River to replace another British ship stationed in Nanking. At approximately 8:30 AM, soldiers in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) began firing at the ship from the shore; Union flags were masted, the ship’s captain increased speed, and the assault soon subsided. But an hour later, as the ship pulled further up the river, the PLA struck again — this time, fatally. Stuart Hett, a 22-year-old lieutenant commander at the time, recalls the nightmarish three-hour attack:

“The first shell burst through the bridge and killed several people. The commander [Bernard Skinner] was mortally wounded. Then they hit the wheelhouse, killed the men on the wheel, and jammed telegraphs. A Third shell hit the power room and removed electricity. The ship went out of control and ran aground. Twenty-five were killed that day.”

In the chaos, Simon, who was thought to have been asleep in the bulkhead beside Skinner, was gravely wounded by shrapnel. As on-board medics treated the wounded sailors and identified the deceased, the cat was quickly forgotten: He slunk into the depths of the ship and disappeared. Over the course of the following week, numerous attempts were made to rescue and recover crew members, but heavy fire prevented any success; spirits plummeted — and Simon, the ship’s morale-booster, was nowhere to be seen. Downtrodden, the crew pronounced him dead.

But eight days later, while the 60 remaining sailors wallowed in grief, Simon miraculously emerged, driven to the surface by thirst. George Griffiths, a private, was the first to spot the “sorry sight:”

“He received shrapnel wounds in his face, back, and left side; his whiskers and eyebrows were burned off by the flash. He refused medical aid and removed shrapnel himself by patient washing (this took him about a week); his hind legs were covered in dried blood, and he was weak, skittish, and direly dehydrated.”

Simon was immediately taken to the medic, stitched up, and began a long healing process — but the cat could hardly wait to get back to his military duties. The ship’s boilers and fans had shut down as a result of the onslaught, and the rats ran freely through the ventilation system; during Simon’s absence, they had infested food supplies, invaded living quarters, and made life a greater hell for surviving crew members.

Despite his injuries, Simon quickly got to business. His first night back, he had two confirmed kills, and within a few days’ time, he’d succeeded in clearing the deck of critters. But one foe remained: A gargantuan rat the crew had nicknamed “Mao Tse-tung.” For weeks, the scoundrel had avoided traps and gnawed his way through sealed food. Simon would have none of it. When the cat finally met his nemesis in the storeroom, he pounced, killed it, and proudly dropped it by the mens’ boots. From then on, the crew hailed him as “Able Seacat Simon” — the first (and so far, only) military title ever given to a feline.

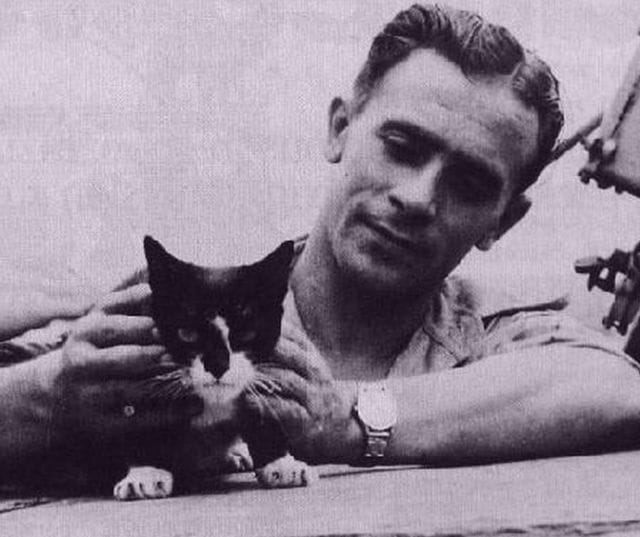

Shortly after the cat’s dramatic reemergence, a man named John Kerans arrived from Nanking and assumed the Lieutenant Commander post. A prolific cat-hater, Kerans was not enamored with the feline; despite Simon’s best efforts (mainly cuddling and bringing the man rats), he failed to win the new Commander over — until the man fell ill. As Kerans lay seasick one night, Simon leapt into his arms; the two fell asleep together and any ill will was soon forgotten. Simon’s sleepiness would forge him many other friendships: The psychologically damaged crew found comfort in the cat’s companionship, and he’d often nuzzle beside them for mutual naps.

For three months, as AMS Amethyst lay stranded, Simon maintained his duties; soon the ship’s morale had improved enough to attempt an escape from the river. On the night of July 30th — 101 days after the ship’s bombing — Commander Karens and his semi-repaired ship set off to make the 104-mile dash to freedom. Miraculously, the boat made its way down the river unharmed, met a rescue ship at sea, and proceeded home.

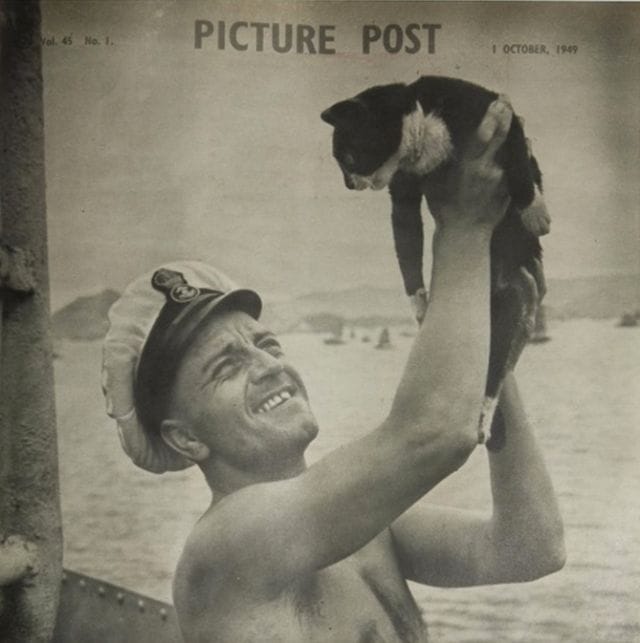

By August 1, news of the crew’s ordeal (now known as the Yangtze Incident) had spread internationally. The crew and their intrepid cat were lauded as heroes: King George VI ordered that the men be given a round of drinks, and during a special ceremony, Simon was decorated with the first of three awards: an Amethyst campaign ribbon.

While docked in Hong Kong, the crew also received a telegram from the PDSA: “At the captain’s discretion,” it read, “we would like to award Simon the Dickin Medal.” Karens, the Commander, quickly responded, including a list of Simon’s “confirmed kills” (rats), and an update on the feline’s health:

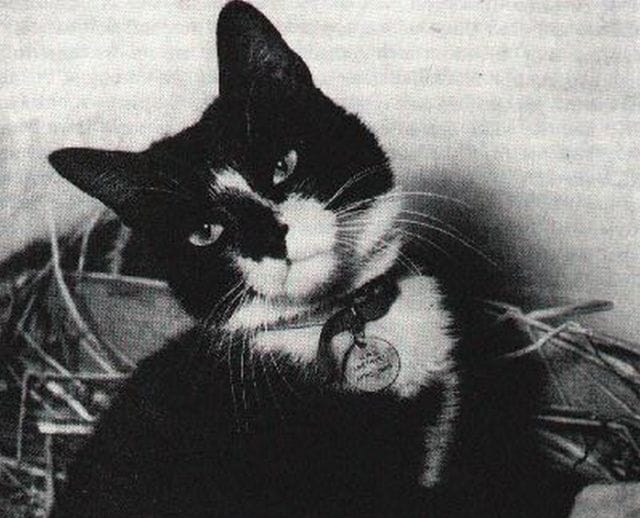

“Simon has now recovered fully from his wounds, although he is still very nervous of bangs and sudden noises, and his whiskers have grown back bent.”

When Amethyst returned to England in November, Simon was greeted with a hero’s welcome, and was showered with photographs (he’d often disappear at the sight of a camera). Fans from around the world sent him “letters, poems, gifts of food, [and] cat toys.” During his six-month quarantine (necessary for all returning crew), he received dozens of daily visits — including a few from Commander Kerans, who planned to adopt him upon his release.

Simon was unanimously awarded the Dickin Medal for his service aboard the ship, and a ceremony was set for December 11. Sadly, he never made it.

Toward the tail end of his quarantine, Simon developed a high fever and acute enteritis (inflammation of the small intestine); on November 28, just two weeks before the ceremony, he passed away at the tender age of three (his award was posthumously accepted by the once-cat-hating Commander Kerans and his wife, and was followed with an honorary Blue Cross Medal). The vet would later state that Simon’s decline was due, in part, to the wounds he’d sustained at war: The companionship of the cat’s crew, surmised his caretaker, had likely kept him alive.

In the wake of the little trickster’s death, newspapers and magazines commemorated his legacy. “The most respected cat in all of Britain,” wrote a Time reporter, “was a small, black, white-bibbed tom named Simon.”

Simon’s Dickin Medal would eventually become one of the most prized naval medals in the world. In the mid-1960’s, when the Royal Navy liquidated its awards, it was sold to a Canadian buyer for “several thousands pounds.” After changing hands several times in various countries, it found its way back to London, where it sold at a 1993 auction for 23,000 pounds ($43,000 USD).

In a “specially made casket wrapped in cotton wool, and draped with the Union flag,” and with full naval honors, Simon was lowered into the Earth in PDSA’s specially assigned cemetery in East London. “Throughout the Yangtze Incident,” reads his tombstone, “his behavior was of the highest order.”

If you enjoyed this post, you’ll be mildly amused by our book → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett; you can follow him on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.