Californians pride themselves on being number one. Highest population. Biggest economy. Top public university system. Most In-N-Out locations per capita. Let us count the ways in which the Golden State comes first in the nation.

But in the competitive category of money spent on gasoline, Californians hold a more dubious distinction: Across the contiguous United States, nobody pays more to fill ’er up.

This is hardly a new trend. With few exceptions, Californians have been paying more than most American drivers since the 1990s. But since an explosion crippled one of the state’s largest refineries last year, the premium on California gas has jumped to unprecedented heights. And they’ve stayed high ever since.

At the peak of driving season last summer, Californians paid over a dollar per gallon more than the typical American driver. While the gap has shrunk this year, it is still well above the historic average. According to the AAA’s running gas price tracker, Californians now pay $2.64 per gallon for regular—over half a dollar above the national average.

At first glance, the culprit for this pricing mismatch might seem obvious.

California also comes first in stringent environmental regulation and, sure enough, taxes, fuel standards, and a newly expanded cap-and-trade program all conspire to make driving in California more expensive.

But not this expensive.

Source: Energy Information Administration, Annual Average Prices for All Grades and Formulations; 2016 Data through August 1

State policy is responsible for about thirty cents of the price gap, analysts say. What explains the rest is the subject of a long standing and heated debate. While some industry analysts claim that the California gas premium is simply the result of the state’s unique and highly regulated position within the national fuel economy, some advocacy organizations point the finger at oil refiners, whom they accuse of artificially restricting supply in order to raise prices and gouge drivers.

With state officials investigating, the California price gap remains an economic mystery. And a very expensive one. Over the last 18 months, California drivers have paid $10 billion more than their counterparts around the country.

That’s a silent tax of $170 per year levied on each resident of the largest state in the country—and nobody knows exactly why.

Taxes, Standards, and Cap-and-Trade

To be sure, there are plenty of explanations of California’s high gasoline prices that do not require allegations of corporate conspiracy.

Chief among them is the state’s high CARB diet. In 1996, new rules came into effect requiring all cars to run on cleaner-burning California Air Resources Board reformulated gasoline (CARB RFG). This requirement raised gas prices directly by increasing the cost of refining, but it also had the effect of walling off the state gasoline market. Not all refineries are capable of producing California’s requisite blend. Though the fuel standard deserves much of the credit for clearing smog out of the L.A. Basin, it also narrowed the pool of potential gas suppliers.

Then, of course, there are the taxes. Consistent with the state’s big government image, taxes on gasoline come out to 54 cents per retail gallon in California—roughly a dime higher than the national average. Last year, the state effectively tacked on another ten cents when gasoline distributors were brought under the umbrella of California’s cap-and-trade program.

All told, from fuel standards, to gas taxes, to emissions trading, California policy guarantees that its resident drivers pay an extra 32 cents more per gallon.

The rest of the price gap comes down to geography, says Michael Green, public relations director at AAA. Much of the country’s oil refining capacity is dotted along the Gulf Coast. When any one of California’s 17 refineries hits a production snag, imports have to make up the difference. And imports aren’t cheap.

“There are no pipelines that go over the Rocky Mountains,” he says, which is why gasoline prices are predictably higher across the American West. “Maybe [imported gas] comes from Asia, maybe it comes through the Panama Canal, maybe it comes from Mexico. Either way, those transportation costs get passed along to consumers.”

And that, says Green, is all there is to it. No shady dealings by money grubbing oligopolists in the refining market required.

“That would be like Apple saying ‘we’re going to make fewer phones,’” he says. “From an economic perspective, it seems unlikely that a refinery would have much to gain in doing that. It would just allow their competitors to sell more product.”

But that argument assumes that competitors will always be at the ready to fill in a shortfall in supply. Recent evidence from southern California suggests that that isn’t always the case.

The Import Puzzle

On February 18 of last year, a “fluid catalytic cracking unit” at the ExxonMobil refinery in Torrance, California, exploded. The blast registered a 1.7 on the Richter scale and nearly ruptured a tank of acid that federal regulators say could have released a cloud of toxic gas out into the surrounding Los Angeles metro community.

Fortunately, only two workers suffered minor injuries, but the effect on the California gasoline market was much more disruptive. The Torrance refinery made up roughly 8% of the state’s CARB RFG producing capacity and supplied just under a quarter of Southern California’s gasoline. After the explosion, output at the Torrance facility was cut dramatically. According to the Energy Information Administration, the state saw a production loss of over 130,000 barrels of gasoline per day in the following months.

California gas prices shot up in the aftermath. From February 9 to March 9, the average retail rate per gallon increased from $2.44 to $3.44. The gap between California prices and the national average more than doubled.

This was all perfectly predictable. Even as the high prices persisted through the spring, the gasoline market appeared to be behaving as one might expect.

“For a month or two, nobody really saw that as a problem [because] that’s just part of California having an isolated gasoline market,” says Severin Borenstein, an energy economist at UC Berkeley and the chair of the California Energy Commission’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee, which has been tasked with investigating price volatility in the state gas market.

But eventually, prices should come down. Even if state refineries are already operating at capacity and can’t make up the difference on their own, gasoline traders have historically responded to output disruptions by shipping CARB gasoline in from other states and other countries. Though it takes time to produce and transport the fuel, this influx of outside supply tends to bring prices back down within several weeks.

But things didn’t work out that way this time. The price gap grew throughout the summer of 2015. Even though the Torrance refinery came back online this May under new ownership, Californian’s are still paying twenty cents more per gallon than anyone can explain based on policy alone.

“Why it has continued this long really is a puzzle,” says Borenstein.

Looking for Answers

It has been a profitable puzzle for California’s refiners.

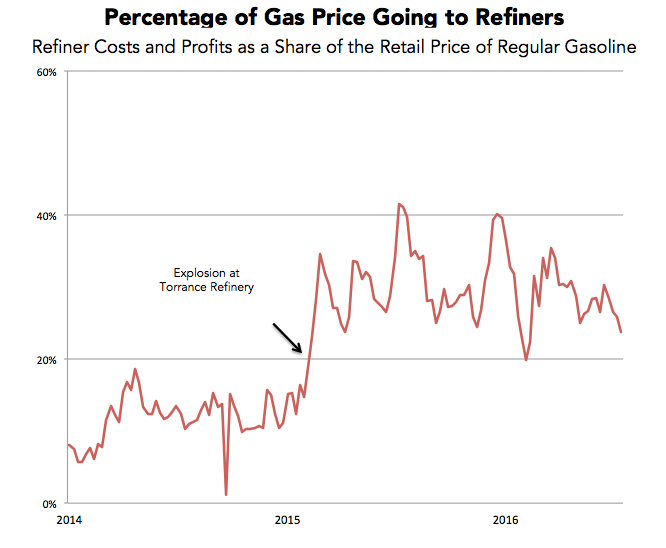

According to estimates produced by the California Energy Commission, the share of each dollar spent on gasoline that goes to refiners jumped after the Torrance explosion. Between the start of 2014 and mid-February of 2015, roughly 12 cents per dollar went to refiners. Since the explosion, the average has been 30 cents and as recently as the end of July, it was still 23 cents. (The refiner margins are slightly lower for gas sold at off-brand gas stations, but the change, from 10% to 25%, is a comparable increase).

Source: California Energy Commission

What industry insiders describe as a happy coincidence, some consumer groups see as a concerted plot.

In a report released last week, the Santa Monica-based Consumer Watchdog, which has long been critical of the California refining industry, noted that the gap between wholesale and retail gasoline prices in California has now reached a historic high.

“There’s no shortage. There are no refinery problems. Where are the savings for consumers?” asked Cody Rosenfield, an advocate for the group, in a press release.

The answer provided by the group is an explosive one: state oil refiners are strategically withholding supply to pump up prices. As evidence, Consumer Watchdog cites a recorded conference call in which the CEO of PBF Energy, the company that purchased the Torrance facility last spring, refers to Exxon’s decision to not “run a single refinery operation in the state of California” after the explosion. The group interprets this as confirmation that Exxon was purposefully dragging its heals in repairing the Torrance facility and that oil refiners are colluding to reduce in-state production and limit imports.

The president of PBF’s West Coast operations called the allegation of collusion “ludicrous” and said that the recording was taken out of context.

Such collusion would, of course, be illegal. But given that only nine firms produce CARB gasoline within the state (and just two control over 50% of the refining capacity), at least the logistics of coordinating amongst in-state competitors would not be too difficult. Finding a way to prevent third-party distribution companies from importing gas would prove more challenging.

Source: California Energy Commission

On that point, Consumer Watchdog has also accused California refiners of offering gas to major off-brand retailers, such as Costco, at significant discounts, in order to discourage them from purchasing gasoline from outside of the state.

Taken together, the allegations provide a possible, if entirely unsubstantiated, explanation for why imports have not rushed into California, despite the state’s high prices, says UC Berkeley’s Severin Borenstein.

“You could tell a combination of stories: In part, it’s this price-fixing or collusion with Exxon, and, in part, it’s cutting deals with the major buyers of CARB gasoline, like Costco and Safeway, in order to prevent importers from having a market,” he says. “It does require a lot of steps. That’s not to say it couldn’t be true, but it’s a pretty complex argument.”

As the chair of the state’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee, Borenstein and his colleagues have been tasked with delving into exactly this kind of complexity. But it’s been slow going, he says. Under California’s government transparency rules, state commissions can only meet in public locations, and communication between meetings amongst members is heavily restricted.

In the coming months, the commission plans to speak with gasoline traders to find out what financial risks and barriers are keeping them from importing gas. They also may consider a recommendation that the state allow the sale of non-CARB gasoline as long as a smog surcharge is tacked on. But for unpaid commission members who live in various locations around the state, Borenstein says the rules have made it challenging to adequately investigate one of the state’s most economically powerful industries.

“If the price of oil goes up to $70 or $80 a barrel, we’re suddenly going to be in the spotlight, and I’m going to get a lot of flack from legislators saying we’ve been looking at this for two years,” says Borenstein. “Well, yeah, we’ve been looking at this for two years—and we’ve had six meetings!”

In the meantime, the state’s top prosecutor appears to be picking up some of the slack. Last June, California Attorney General Kamala Harris, who is expected to fill one of the state’s U.S. senate seats this November, issued subpoenas to the state’s major refiners.

Few Complaints

Of course, it’s possible the economic mystery of California’s high gas prices will be resolved soon enough—as a political issue, if not an economic one—as prices continue to fall.

Californians still pay some of the highest gas prices in the country, but the state has seen the fastest year-over-year decline of any state in the country. Since last August, the average price has fallen by over a dollar. This may be a testament to how out of whack prices were just twelve months ago, but it also makes it less likely that gasoline costs will be a salient political issue anytime soon.

In fact, this relative complacency among consumers may offer yet another explanation for why the price gap is so persistent, despite the restoration of the Torrance refinery, says AAA’s Michael Green.

“Gas prices are very much based on expectations,” he says. “There’s less motivation for gas stations to drop their prices as quickly, because a lot of people are happy to see prices where they are today.”

In the meantime, demand has been picking up. According to Green, 2016 is set to be busiest driving year in American history. Regardless of whether Californians are getting ripped off every time they fill up, at least for the time being, they may not know what they’re missing.

Our next article examines the economics of the cheap, delicious rotisserie chicken. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Want to write for Priceonomics? We are looking for freelance contributors.