“We’re talking about a show for 1- to 4-year-olds; if we had homosexuals in it, they wouldn’t even know it. Tinky Winky is simply a sweet, technological baby with a magic bag.”

~ Teletubbies producer, Kenn Viselman

![]()

When Teletubbies debuted on the BBC in March 1997, it almost immediately polarized viewers. Some thought the show was a work of genius — an unprecedented effort to create educational content for one-year-olds; others found the plot repetitive and the characters horrifying (“These spacemen will frighten our children,” one concerned German told The Independent).

But there was one thing everybody could agreed on: The series was incredibly strange.

Four rotund, baby-faced, asexual aliens — Po, Laa-Laa, Dipsy, and Tinky Winky — spent the vast majority of each 25-minute episode waddling about in a pristine country landscape, speaking in high-pitched gibberish and interacting with talking flowers. On occasion, they’d slide down into the “Tubbytronic Superdome” (a high-tech underground cavern) and carouse with an anthropomorphic vacuum cleaner. Other times, they’d awkwardly slurp on tubs of pink custard while reveling in their mutual buffoonery. Fitted with interactive screens on their stomachs and antenna-like communication devices, the characters would often broadcast the repetitive, mundane lives of human children, then applaud their efforts enthusiastically, as if they’d just cracked some age-old mathematical code.

The show’s producers (Ragdoll Productions) and distributors (BBC in the UK; PBS in the US) shared the characters’ elation: Teletubbies was a runaway financial success. After just one season on air, the show had attracted two million viewers per episode, grossed $800 million in merchandise sales, and launched a best-selling preschool book series. Even the program’s theme song, “Teletubbies say ‘Eh-Oh,’” saw explosive dividends — it sold over a million copies and topped the UK Singles Chart for 32 weeks. BBC proudly touted the show as a “case study” for making money. “The potential on this one is limitless,” the network’s head of sales told a room full of international distributors; within two years, Teletubbies was being broadcast in 120 countries in 45 languages.

But all wasn’t well in Teletubbyland: With instant success came bountiful controversy: Did the meandering plot hold any educational value? Should children under the age of two even be watching television? Stranger, non-scientific accusations were also made: Did the colorful, repetitive nature of the show provide an ideal experience for college kids tripping on psychedelic drugs?

And then, sparked by the grumbles of parents and pundits, the strangest accusation emerged: Tinky Winky, the purple teletubby, was gay. Despite the character’s asexuality, and the fact that he was fictional, the story snowballed into a media sensation. The “outing of Tinky Winky” would become, in the words of the show’s producers, the second biggest news story after “Monica Lewinsky and her blue dress.”

This is the true story of how Tinky Winky, the purple Teletubby, incited a decade-long homophobic panic.

The Rise and Fall of Tinky Winky

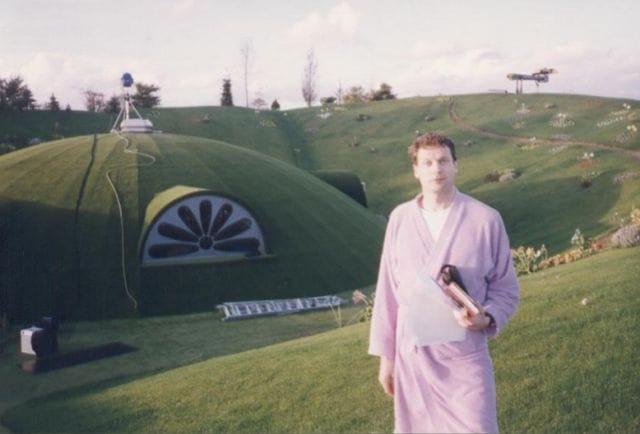

Dave Thompson, the original Tinky Winky actor, on the Teletubbies set (1996)

When a casting call for Teletubbies went out in the Spring of 1996, more than 600 actors auditioned for the role of Tinky Winky. Among the hopefuls was Dave Thompson, an English stand-up comedian and all-around “nutcase.”

Weeks earlier, a casting director for the show had come across Thompson on the set of another television program, Harry Hill’s Fruit Fancies, where he’d portrayed a fully-wrapped Egyptian mummy. “He was impressed that I wasn’t claustrophobic,” recalls the actor, “and he figured that was a good trait to have in the Teletubbyland, where you’re inside a costume all day.”

Despite being an hour and half late to his call-back, Thompson was given an opportunity to prove his worth: He was swiftly led into a small room, asked to perform an impromptu comedy sketch about childhood, then was paired off with other wanna-be ‘tubbies in a series of “unusual” group workshops. Miraculously, he landed the job. “There are a whole load of people who specialize in wearing costumes — what they call in the trade ‘suit performing’,” he clarified in an English podcast, “but they wanted a person who had something else to offer. I guess I was the guy.”

Thompson, with the rest of the cast, was whisked away to a remote countryside farm in Stratford-upon-Avon (the coincidental birthplace of Shakespeare), and filming for the series commenced. Though he towered above his fellow cast members at 6’3” — nearly 8 feet tall with his costume on — crafty camera angles made him appear much smaller, so as not the scare infantile viewers.

As temperatures rose through the summer, portraying the purple Teletubby soon became taxing for the big man. “It was very, very hot in the costume,” Thompson says. “By lunchtime, I could actually ring a pint and half of sweat from my clothes underneath.” The suits, which cost about $57,000 each, were as difficult to maneuver in as they were stifling; an intricate system of bicycle brake levers in the hands controlled the eye and hand movements, wriggling into the get-up required a small village of production assistants, and the head was nearly impossible to see out of:

“It was all, ‘this many steps this way, that many steps this way, turn your head this way.’ You couldn’t actually see and you didn’t actually know what was going on and what people were doing around you. We were all being sort of controlled.”

Despite these difficulties, Thompson’s rendition of Tinky Winky initially dazzled the show’s director. For the actor, it was a “dream Summer” — full of praise, pats on the back, and positive encouragement. Then, things began to turn sour.

When it came to narrating the character’s giggles and squeals in the studio, Thompson’s voice was suddenly “too high-pitched;” a voice-over actor was swiftly brought in to do a “proper job,” giving the actor little chance to correct his tone. As production wrapped up for the first season, Thompson received a letter, seemingly out of the blue: “Your interpretation of the role of Tinky Winky” has not been accepted.” With that, he was terminated from the show’s cast before it even aired.

“I wasn’t given any clues as to what I was doing wrong,” he recalls. “I was officially asked to leave in a letter from an accountant just before everyone else went off to the end-of-shooting wrap party.”

Dave Thompson: The original Tinky Winky

“I am proud of my work for them,” the mustachioed actor later ceded. “I was always the one to test out the limitations of the costume. I was the first to fall off my chair and roll over. I took all the risks.” It was likely these “risks” that resulted in his departure: According to a few of his old co-workers, Thompson had a penchant for “romping around naked” between takes — a quirk that had once earned him the nickname “Kinky Winky” on set.

The purple teletubby subsequently seemed plagued: Over the next five years, two more actors portrayed the role (the other three teletubbies each had only one actor for the duration of the entire series). Though “most of the program is made up of generic shots” which feature Thompson (even in later episodes), he sees no dividends. “When they brought the new guy in, that was just for a couple of the dances and for the little sketches,” he says. “So even in the ones with him, I am actually in the show more — though I don’t get paid a penny for it!”

Thompson eventually returned to comedy, and became known for his “naked balloon dancing” — particularly the routines he acted out in public parks in Bath, Somerset. He also penned a book, “The Sex Life of a Comedian,” which tells a familiar story: A Stand-up comic gets a job wearing a furry costume on a kids’ television show and then gets fired.

Tubbygate: How Tinky Winky Incited a Homophobic Panic

On March 31, 1997, Teletubbies made it’s public debut on England’s BBC Television. Before long, the show’s purple character began to fall under scrutiny.

It began in July, with a letter to British popular culture magazine, The Face. “Tinky Winky,” wrote Sussex University lecturer Andy Medhurst, “may be the first queer role model for toddlers.” A few days later, The Guardian, trumpeted the purple Teletubby as “a gay icon who prances around in a particularly campy way” (“campy” being British slang for “blatantly homosexual”). The British media opened its floodgates: Over the ensuing months, dozens of talk shows, radio programs, and newspapers hotly debated the sexuality of the children’s show character. As Thompson’s firing became public information, the media gave it a sensational spin: The actor had been let go for “acting too gay.”

At the same time, the show’s popularity soared. By the end of the first season, nearly $800 million in merchandise — pajamas, toys, and videos — had been sold, garnering the interest of networks across the world. Distributor PBS recognized its potential, bought the American rights, and, in the Spring of 1998, began airing the program in the United States. Soon enough, the Tinky Winky controversy crossed international lines.

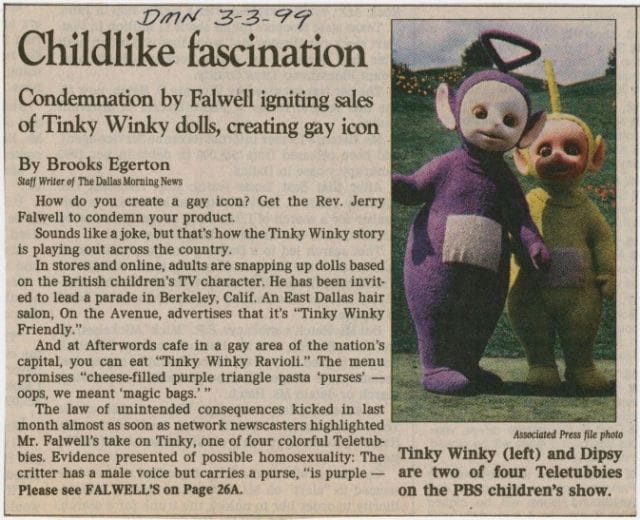

With news of the Teletubbies’ US arrival, The Washington Post swiftly declared that “the gay Tinky Winky” was the “new Ellen Degeneres” (implying that Degeneres’ time as the “chief national gay symbol” was over, and that the Teletubby was taking her place). “Tinky Winky comes across as a big fabulous fag,” declared LGBT magazine, The Advocate. “He’s become as gay icon…[and] the same fundamentalists that boycott Disney are going to flip when they see him.”

![]()

By the 1990s, Reverend Jerry Falwell was running out of people to pick on. The evangelical Southern Baptist pastor had spent his life championing the values of the extreme Christian right: He’d caroused with shady politicians, crusaded against secular curriculums in the classroom, and, most notably, established himself as “the founder of the anti-gay industry.”

When the news finally came around to him that a children’s show character was purportedly gay, he wasted no time opining. In the February 1998 issue of National Liberty Journal (a promotional publication for the university he’d founded), he wrote a scathing critique of “Teletubby culture.” The pundit’s one-paragraph diatribe, titled “Parents Alert: Tinky Winky Comes Out of the Closet,” fittingly began in all-caps — “PARENT ALERT…PARENT ALERT” — before expounding on the dangers of asexual fuzzy creatures.

“He is purple – the gay pride color; and his antenna is shaped like a triangle – the gay-pride symbol; he flaunts a red purse,” the pundit furiously declared. “As a Christian, I feel that [Tinky Winky’s] role modelling of the gay lifestyle is damaging to the moral lives of children.”

Anti-gay crusader Rev. Jerry Falwell clings to a Tinky Winky statue jokingly presented to him at a Baptist church in San Diego, CA (1999)

A few days later, he was given an opportunity to wax his theory on NBC’s “Today” show. “To have little boys running around with purses and acting effeminate, and leaving the idea that the masculine male, the feminine female is out, and gay is O.K. — that’s something Christians do not agree with,” he gruffly told host Katie Couric.

“We’re talking about a show for 1- to 4-year-olds,” countered Teletubbies producer Kenn Viselman, also on the show. “If we had homosexuals in it, they wouldn’t even know it — but for the record, we don’t. Tinky Winky is simply a sweet, technological baby with a magic bag.”

Aired on national television, this “debate” catapulted Tinky Winky’s sexual status into the limelight. “This ridiculous question — ‘Is Tinky Winky a heterosexual or a homosexual?’ — became the second largest story in the world,” the show’s producer later stated. “Literally the only story that got more global [attention] was Monica Lewinsky and her blue dress.” Similarly, the TInky Winky controversy became political: While ultra-conservative pundits sided with Falwell, and agreed that the show was “sexually edgy,” Democrats maintained that attacking a children’s show character was “simply mystifying.”

The more reasonable sector of the media pointed to the absurdity of the entire debacle: Teletubbies, as non-gendered, non-sexual creatures, could be neither gay nor straight. As one journalist commented, “The Teletubbies have no genitalia — how could they have any sexuality?” Steve Rice, the show’s spokesman, was quick to share these viewpoints:

“The fact that he carries a magic bag (which isn’t a purse, by the way) doesn’t make him gay. It’s a children’s show, folks. To think we would be putting sexual innuendo in a children’s show is kind of outlandish. To out a Teletubby in a preschool show is kind of sad on his part. I really find it absurd and kind of offensive.”

Meanwhile, at the New York Toy Fair, Tinky Winky plush dolls sold like hot cakes. “All [Falwell] has done is make a mockery of himself,” said Jim Silver, a toy industry insider, told the New York Times. “If anything, it put more attention on Teletubbies and increased sales.” The controversy also started a new trend among the city’s “gay hipsters:” Tinky Winky backpacks, t-shirts, and keychains became unofficial badges of solidarity in the community.

Representatives of the gay community responded to the character’s outing, and the media storm surrounding it, with humor. “We haven’t spoken to Tinky Winky directly, and so we don’t presume to know what his orientation may be,” a spokeswoman for the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force told the Chicago Tribune. “However, we think it’s a great thing that the Teletubbies portray human diversity and that children love the Teletubbies and appreciate the diversity of expression that the Teletubbies represent.”

Like most tittle-tattle, Tinky Winky’s perceived orientation didn’t die away: For years, what started out as mere speculation became an accepted truth.

Poland’s Anti-Tinky-Winky Crusade

By 2001, Tinky Winky rumors were still in circulation (the character’s sexuality became an everlasting topic of discussion at dinner tables and schoolyards), but Teletubbies controversy began to transition to a more pressing concern: Did the show actually have any educational merit? Though its creators — a speech pathologist and a former schoolteacher — seemed gung-ho about “stimulating toddlers’ imaginations and developing their motor skills,” experts pointed out the lack of evidence behind these claims. Susan Linn, a psychiatry chair at Harvard Medical School, voiced these concerns in a column for The American Prospect:

“There is no research showing that the program helps babies learn to talk. There’s none to suggest that it facilitates motor development in 12-month-olds. There is no data to substantiate the claim that young children need to learn to become comfortable with technology. In fact, there is no documented evidence that Teletubbies has any educational value at all.”

With mounting pressure from education specialists, BBC discontinued the show in 2001; in the United States, new episodes were pulled in 2005 — though reruns continued to air until 2008. By this time, the show had spread to 120 countries and was being aired in 45 languages: Right after the United States discontinued Teletubbies, government officials in Poland resurrected the ten-year-old Tinky Winky debate — this time, with the mission to “scientifically prove” that the character was, indeed, a “homosexual.”

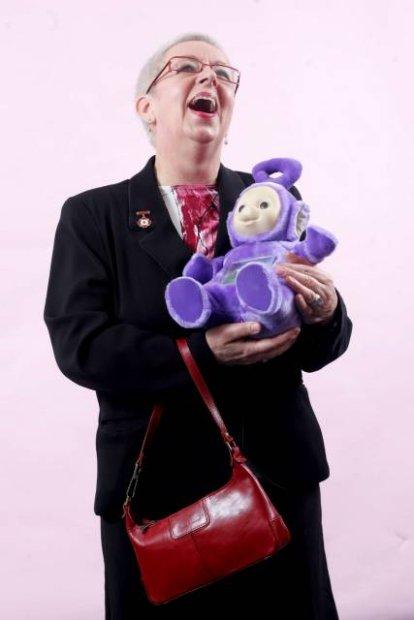

Ewa Sowinska, as the country’s child rights ombudsman, was tasked with investigating complaints against faulty administration. In lieu of the the many pressing issues awaiting her response, Sowinska instead decided to hone in on the purple Teletubby.

Sowinska following Jerry Falwell’s lead (it’s trendy for anti-gay political figures to do photo ops with Tinky Winky!); Fot. Bartosz Bobkowski / Agencja Gazeta

“I noticed [Tinky Winky] has a lady’s purse — but I didn’t realize he’s a boy,” she told a local magazine. “At first I thought the purse would be a burden for this Teletubby…Later I learned that this may have a homosexual undertone.”

Sowinska then embarked on a voyage to recruit the country’s “top child psychologists” to determine whether or not merely watching the program could encourage children to engage in homosexual acts. After pursuing the idea for a week, Sowinska announced her findings to the media, as if revealing some groundbreaking study: “The opinion of a leading sexologist, who maintained that this series has no negative effects on a child’s psychology, is perfectly credible; as a result I have decided that it is no longer necessary to seek the opinion of other psychologists.”

With these “findings,” Sowinska came under heavy criticism and began to backpedal. “They are fictional characters, they have nothing to do with reality,” she ceded days later. “The bag…and other props the fictional characters use are there to create a fictional world that speaks to children.” Concerned that the politician was “turning the department into a laughing stock,” Speaker Bronislaw Komorowski ordered her termination from office just months later.

Poland wasn’t the only country to reignite a stir over Tinky Winky: In Kazakhstan, the character — and the show in its entirety — was banned by personal order of the president on the grounds that “he was a sexual pervert.”

A Burden to Carry

Looking back, Dave Thompson isn’t exactly sure why the purple character’s sexuality was ever in question. “The mistake was that adults projected adult sexuality onto these pre-sexual creatures,” he reflects. “They’re aimed at children under 5, so they don’t want them to have sexuality for very obvious reasons.”

Nikki Smedley, the actress who played the yellow-hued Laa-Laa, finds the controversy equally absurd. “What kind of person can take the obvious innocence and turn it into something else?” she asks. “We were hardly sexual beings.” When the 49-year-old was first exposed to the show, she thought it was a work a genius; she appreciated that it “came from a place of love,” and that it strived to wholesomely engage young children. “Somewhere in the world,” says the actress, “a child is looking at Laa-Laa and laughing — that’s beautiful.”

For the better part of a decade, Tinky Winky also evoked laughter — often under the wrong circumstances — though, he’ll soon have a shot at redemption: Two months ago, the BBC announced a 60-episode renewal of Teletubbies — the first new production in nearly a decade. The characters, says the network, will be “revamped” and modernized, though it’s unclear whether he will sport his trademark accessory.

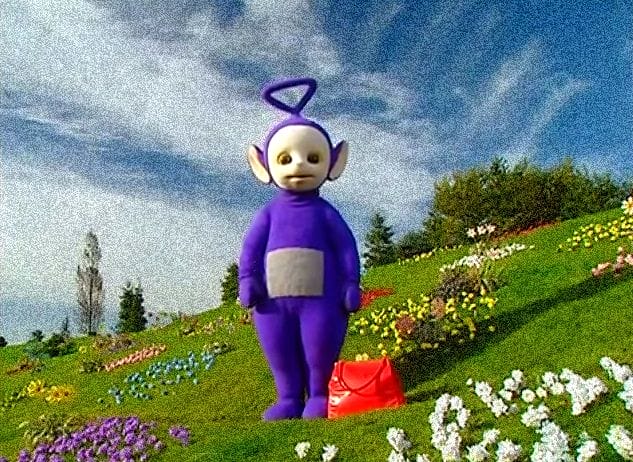

![]()

It would be difficult to imagine the exuberant creature without his red magic handbag. Season after season, it brought him joy, excitement, friendship — in many ways, it defined who he was. But a scenario in a later episode paints a sad picture.

Tinky Winky hobbles on screen and looks around: He’s alone. Gingerly, he removes the red handbag from his shoulder, places it on the ground, and stuffs it with everything he can find: a patterned hat, a scooter, a giant bouncy ball, a piece of toast — it’s soon full to the brim. He shuts the latches, and proudly shuffles a dance. He bends to pick up the bag, but is unable to lift its weight.

He pauses, as if uncertain how to proceed, his triangular aerial lightly flopping in the breeze. And then, with a defeated squeal, he voices his dilemma: “Uh-oh!”

His bag had become too big of a burden to carry.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett; you can follow him on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.