Consider the state of Nebraska. What comes to mind?

Common associations with the Cornhusker state include: row crops, silos, college football, Warren Buffet, and wholesome, earnest Americana.

Now try this one: Refugee Capital of the United States.

So far this year, the City of Omaha has settled over 900 people fleeing war, persecution, and disaster around the world. That may be a small figure relative to the estimated 21.3 million refugees worldwide (or relative to the population of Omaha, for that matter, which is roughly 434,000). But it’s still higher than the number of refugees resettled in Los Angeles and New York City combined.

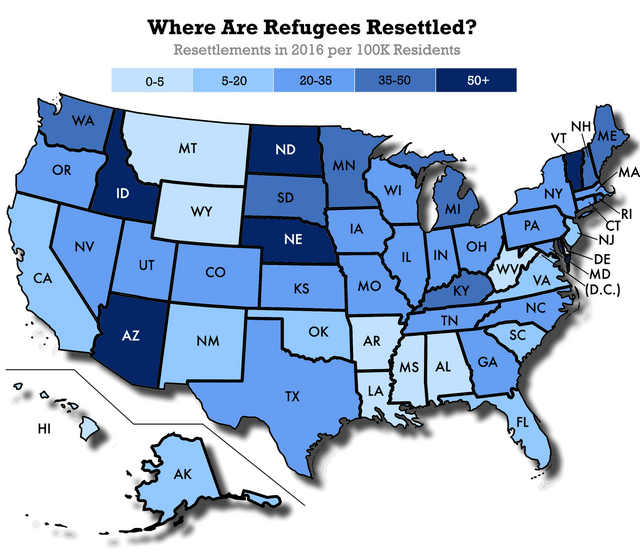

That disproportionate hospitality extends across the entire state, where over 1,300 refugees have found new homes this year. That may not be much compared to the resettlement statistics in larger states, like California, Texas, and New York. But given Nebraska’s population of fewer than 2 million, on a per person basis, this makes the state the most welcoming of refugees in the nation. For every 100,000 residents, Nebraska resettled roughly 71 refugees in 2016. By the same measure, California welcomed fewer than 18.

If these figures don’t jibe with your understanding of where refugees live in the United States, that might be because you’ve been following this year’s presidential election. When Donald Trump claims that we “have no documentation” about the “Trojan horse” refugees who live in this country, and when Republican governors across the country insist that they will not abide Syrian refugees resettling within their borders, they not only raise suspicions about some of the world’s most vulnerable people, they fundamentally mischaracterize what may be the most complex human relocation system on the planet.

This is a system in which international, federal, and charitable organizations all work together to bring more refugees to the United States than any other country—and which places more of them in Boise, Idaho; Des Moines, Iowa; and Bowling Green, Kentucky; than in New York City.

How does this system work and how did we get to this point?

Somalis in the Buckeye State

If you’re looking to answer these questions, a good starting point might be Columbus, Ohio.

Over the last two decades, the city has become one of the most popular resettlement locations for those fleeing war, persecution, and deprivation in Somalia.

To be clear, this population represents a small trickle of all Somalis hoping to leave the country or the refugee camps in adjacent Kenya. The refugee application process is notoriously complex and time-intensive. An aspiring refugee must first get a referral from the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees or from a local embassy before they even have permission to apply for refugee status. This application process requires extensive pre-screenings, background checks, health examinations, and on-site interviews. From start to finish, the process can, and generally does, take years—and of those who make it to the screening phase, only half are ultimately resettled.

Still, many are. Over the last ten years, the United States has resettled over 70,000 Somali refugees. Many have come to Ohio. Today, Columbus has the second largest Somali population in the United States after Minneapolis.

Why Columbus, of all places?

Data: Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System, U.S. State Department.

“The short answer to your question is: it’s complicated.”

That’s the response from Tamar Forrest, the Director of Development at the Economic and Community Development Institute in Columbus, Ohio. The ECDI was founded by a refugee from the Soviet Union in 2004 and provides various social and economic development services to Columbus’ sizable Somali refugee community.

“For one, we’re a bit of a victim of our own success,” she says. “Our resettlement agencies are really, really good.”

When a refugee is finally approved for resettlement in the United States, the State Department matches the applicant with one of nine resettlement organizations. These are non-profits, many of them religiously-affiliated, and they—not federal or state governments—are the organizations that decide where a refugee will be resettled.

That decision often comes down to logistics, says Forrest. Does a city have enough affordable housing? Does the resettlement organization have a local network of ESL teachers and caseworkers to refer to? Are there organizations like ECDI on the ground ready to help with job training and financial literacy courses?

But once a refugee community is established in a specific town or city, it begins to exert its own gravitational force. Resettlement agencies will often try to place refugees from a particular country into a community in which they have family or community ties to draw upon. And so Somalis are resettled in Columbus because Somali refugees have been placed in Columbus in the past.

This process takes place with or without the resettlement agencies, says Forrest.

“There were people in Columbus, like Bantu Somalis and Somalis, calling their family and friends in the refugee camp in Kakuma [in Kenya],” she says. “And they were saying, no matter where you go—if it’s Atlanta, if it’s Chicago, if it’s New York—you have to make it to Columbus.”

Of course, it’s common for refugees to move from the town or city in which they are initially placed. These “secondary migrations,” as scholars call them, mean that official refugee resettlement statistics (like the data used to make the map at the top of this article) offer an incomplete picture at best. In a paper that Forrest co-authored with Ohio State University professor Lawrence Brown in 2014, she estimated that between 2000 and 2005, over 2,500 refugees left California for other states, while over 1,000 resettled in the Golden State.

This national reshuffling also serves to reinforce the placement decisions of resettlement agencies. As the local Somali community grows in Columbus, more Somali refugees from around the country move there, which encourages resettlement agencies to resettle more Somalis in Columbus, which causes the local Somali community to grow, and so on.

Data: Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System, U.S. State Department.

Thus, what is effectively a choice of convenience by one of nine non-profits across the country can establish an American city as the go-to locale for a specific refugee community.

It’s a common story. This is the reason that so many refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo have recently been resettled in Atlanta (1,198 in the last three years), why so many Syrians now live in San Diego (871), and why you can now find so many Iraqi refugees in Houston (1,783).

Iraqis in Houston

Ali Al Sudani is one of those Iraqi refugees.

When Sudani arrived in Houston in 2009, he knew close to nothing about the city. Having spent the previous three years working for an NGO in Jordan and applying for refugee status, his understanding of life in Texas was derived solely from television.

In three words: “Cowboys, guns, and the oil industry,” he says.

Still, his boss had family in Houston and had spoken highly of the economic opportunities there. And so after a year of referrals, applications, background checks, health inspections, and cultural orientation courses, he boarded a plane for George Bush Intercontinental Airport.

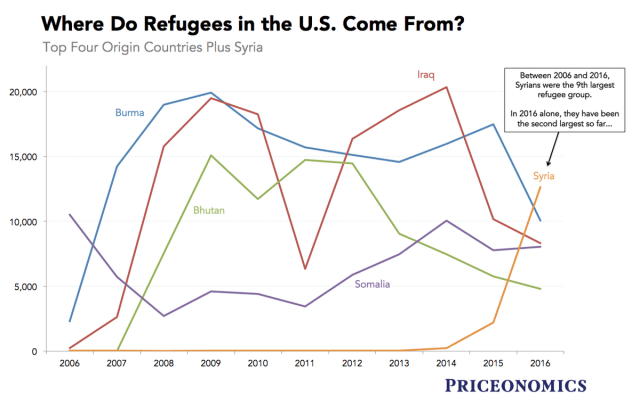

Sudani was not alone. As the United States military began to slowly withdraw from Iraq at the end of 2007, Iraqis like Sudani, who had spent the years of the U.S. occupation working with coalition troops or foreign NGOs, were being targeted for retaliation in ever growing numbers. For both humanitarian and political reasons, the U.S. State Department began ramping up the number of refugee applications that it processed from Iraq and the camps in Jordan.

But when Sudani’s plane landed in in Houston in 2009, there were still relatively few Iraqis in the city. A local charity, Interfaith Ministries for Greater Houston, helped him secure an apartment in the southwest corner of Houston, but they had few Arabic-speaking caseworkers and most of Sudani’s refugee neighbors were Cuban.

Though Sudani had learned to speak English while working with American and British troops in Iraq, he still enrolled in the ESL and cultural orientation courses offered out of his apartment building. This gave him a chance to meet his neighbors and to learn how to navigate some of America’s more mysterious institutions: how to open a bank account, how to find a doctor, how to traverse Houston’s infamous five-level stack highway interchanges without crashing his car.

Two months after he arrived, Interfaith Ministries, the same charity that had helped Sudani get situated, offered him a job. Every day, more Iraqis were arriving in Houston and the organization desperately needed someone who could connect with the burgeoning Iraqi community.

Data: Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System, U.S. State Department.

That community was growing every day. Sudani could see that firsthand from where he lived.

“In the apartment complex that I used to live in, I was the only Iraqi,” he recalls. “And then there was another guy. And then another family…But later on, over the last two or three years, I think it was a large community of Iraqis living in that apartment complex and across that neighborhood.”

Six years later, Sudani is now Program Director or Refugee Services for Interfaith Ministries for Greater Houston. These days, that’s a very busy job. In the last ten years, Houston has resettled more refugees than any other city in the country. (Though that rank is arguably shared with San Diego, if you include nearby El Cajon).

Why is it that Houston, of all places, has been the most welcoming city for the tired, poor, huddled masses of the word? Is it the local network of resettlement services? The large international community? The proximity to a large airport?

That may be be part of it, says Sudani. But he also offers a more straightforward explanation: “Houston has a strong economy and the cost of living is affordable.”

“Refugee are normal people,” he says. “They’re just in abnormal circumstances.”

Our next article explores how two statisticians solved a 150-year-old mystery about Alexander Hamilton. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Announcement: The Priceonomics Content Marketing Conference is on November 1 in San Francisco. Join speakers from Andreessen Horowitz, Slack, Thumbtack, Priceonomics and more.

Get your ticket here.