The life of a taxi driver is hard. When cabbies start a shift, they owe about $100 to their company as payment just for the opportunity drive a taxi. They might not break even until halfway through their shift, or maybe not at all that day. In most American cities, they have to work very long hours to make a living.

During a shift, taxi drivers play a strange form of roulette when they pick up anonymous customers. The customer could be a pleasant family that tips them well, a drunk college kid that vomits in their car, or a violent criminal that robs and assaults them. After the customer leaves the car, there is no record of their behavior in the taxi.

Why is it that taxi drivers have to pay their companies for the privilege of doing a difficult and dangerous job? After all, when you show up to your office, you don’t pay a fee to your boss every morning.

The reason taxi drivers have to pay for the right to work is that they need access to a taxi medallion to do their job. A medallion is a permit issued by the government that is required to drive a cab in most cities in America. If you don’t use the medallion yourself, you can rent it out to other drivers on your own or, more commonly, through a taxi company. Taxi companies that rent out access to the medallions have immense economic power over the drivers. If you’re not willing to basically become an indentured servant to get medallion access, well, you’re out of luck.

Taxi medallions are scarce, which is what makes them powerful. It also makes them expensive; medallions sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars on secondary markets depending on the city. In most American cities, there is a hard cap on the number of permits issued. That number doesn’t change for years or even decades. This scarcity of medallions is also the reason it’s so hard to find a taxi in many American cities (cough cough, San Francisco).

But what if you didn’t need a taxi medallion in order to drive people around in exchange for money? A number of startups are doing just that, pioneering a movement called “ride-sharing” where drivers are typically just regular members of the community driving their own cars around in exchange for money.

If anyone with access to a car and cell phone app could become a driver, what would happen to today’s taxi drivers, the owners of medallions, and the industry that exists to extract value from the scarcity of the medallion?

Taxi Medallions 101

The current structure of the American taxi industry began in New York City when “taxi medallions” were introduced in the 1930s. Taxis were extremely popular in the city, and the government realized they needed to make sure drivers weren’t psychopaths luring victims into their cars. So, New York City required cabbies to apply for a taxi medallion license. Given the technology available in the 1930s, It was a reasonable solution to the taxi safety problem, and other cities soon followed suit. (Many of them have different names for the licenses, but we’ll refer to them all as medallions.)

But the taxi medallion requirement had an unintended consequence – it made taxis scarce. The “right” to drive a taxi become very valuable as demand outstripped supply. When this medallion system was introduced in New York City in 1937, there were 11,787 issued. That number remained constant until 2004. Today there are 13,150.

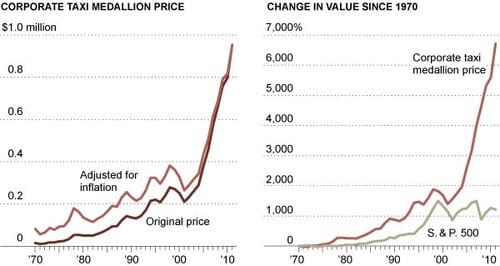

As demand for taxis has increased with supply relatively fixed, the cost of the medallion in New York City has skyrocketed to over a million dollars a year. Even after adjusting for inflation, taxi medallions prices are absurd:

In Boston, the price of a medallion is $625,000. In San Francisco, you need to drive a taxi at least 10 hours a week if you want to hold a medallion and lease it out. Veteran taxi drivers are able to sell their medallions for $300K and the city of San Francisco takes a $100K commission on the sale.

In the taxi market, there are three players: The medallion holders that have the ordained right from the government to operate a taxi, the taxi driver that pays the medallion holder to drive the taxi, and, sitting in between these two parties, the taxi dispatch company. A pure middleman, the dispatch company facilitates the transmission of funds between medallion holders and provides some infrastructure like scheduling, fleet maintenance, and occasional customer leads for the taxis.

There is some overlap between these three entities. Sometimes drivers own medallions, or taxi companies hold medallions. Still, it’s useful to isolate these three main economic interests in the taxi industry. How each of them reacts to industry disruption is very different.

The Taxing Days of Taxi Drivers

In America, we often complain about taxis. They’re never around when it’s raining, they don’t show up when you need to get to the airport, the interiors are filthy, and the drivers talk on the phone and drive aggressively. But as bad as consumers have it, the taxi drivers have it worse.

The root cause of taxi drivers’ problems is that they need access to a medallion in order to drive and make a living. Because of this, taxi companies that distribute medallion access can charge usurious fees and freely abuse the drivers. If the drivers don’t like it, well, then they can’t be taxi drivers then.

In a study of Los Angeles taxi drivers, UCLA professors Gary Blasi and Jacqueline Leavitt found that taxi drivers work on average 72 hours a week for a median take home wage of $8.39 per hour. Not only do they have to pay $2000 in “leasing fees” per month to taxi companies, but the city regulates things like what color socks they can wear (black) and how many days a week they can go to the airport (once). None of the drivers in the survey had health insurance provided by their companies and 61% of them were completely without health insurance.

Recently, the Boston Globe, published an undercover expose on the Boston taxi industry. One of their writers (who used to drive a cab in college) started driving a taxi for a company called Boston Cab. He discovered a corrupt system where medallion access empowered taxi dispatchers to abuse drivers.

The writer describes the fees drivers faced as follows:

Boston Cab charges him the standard shift rate of $77, plus an $18 premium for a newer cab, as well as a city-sanctioned, 30-cent parking violation fee. Factor in the sales tax ($5.96) and optional collision damage waiver ($5), and his cost per shift is $106.26, not including gas.

In order to get the opportunity to pay this $106 fee, taxi drivers had to bribe the dispatchers to get good shifts or to drive at all. The author waited around for hours before he could drive a taxi since he didn’t bribe the dispatchers.

On top of the base fees the driver owed the taxi company for each day of work, the taxi company would arbitrarily make up fees that drivers needed to pay. In the Globe reporter’s case:

After every shift, the reporter fills his gas tank at a station less than three blocks away.

He pumps until the gas gurgles over, once onto his shoes.

Yet when he reaches the garage one night, the gas attendant tells him he owes the company an additional $2.09.

“How is that possible?’’ an attendant is asked, told about the overflowing gas tank.

“It happens to everyone,’’ the attendant says, shrugging.

Passengers often complain that they feel unsafe in a taxi with an aggressive driver. But the drivers are ones who have to worry about safety. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a taxi driver is one of the top ten jobs that result in work related fatalities. The odds of taxi drivers dying because of work related fatality is even higher than for police officers. Picking up anonymous strangers that could be violent late at night while carrying a lot of cash is risky. Just sharing the road with other drivers is risky too. In the case of the Boston Globe undercover driver, he (and his passengers) ended up in the hospital when a drunk driver ran a red light and crashed into his car.

Medallions require that drivers get permission from someone else to drive a cab. This power asymmetry gives the medallion-holders a lot of leverage over drivers and it appears that they abuse it.

And Here Comes Disruption Like a Frigging Train

A number of mobile phone apps, however, are replacing taxi dispatch services and allowing anyone with a car to become a taxi driver without needing access to a medallion. Increasingly, if you want to become a taxi driver, all you need is a car and an app that tells you where to pick up passengers.

In the last half decade, two trends conspired to end the taxi medallion regime. First, people are more comfortable with trusting strangers. This is evidenced by the success of the company AirBnB where regular people people rent out extra rooms in their home to strangers. Marketplaces like AirBnB provide the data (reviews of guests and hosts), brand, and insurance that allow strangers to trust each other.

The second trend is that we all carry around location enabled sensors in our pockets in the form of our phones. Before smart phones, the best way to find a taxi was to go outside and wait for one on the streets like an idiot. Now, you can click a button and an app that knows your location can connect you with the nearest car. Since you can see reviews of the driver, you can trust that it’s safe to get in the car.

The ride-sharing economy started conservatively with Uber allowing anyone to call a black town car via its app. That quickly led to companies like Sidecar and Lyft, that let anyone with a car act as a taxi driver and hybrid services like InstantCab that lets taxi drivers and community drivers both get fares. These companies and their products are called “ride-sharing” apps.

Cheekily, if you hail a ride using one of these ride-sharing apps, the payment is called a “donation.” This sort of seems like a made up legal loophole that can justify any behavior (“Officer I wasn’t paying for sex, I was making a donation!”). But for now that’s one of the ways ride-sharing apps nominally get around local regulations that restrict who can be a taxi.

The Advantage of the Ride-Sharing Apps

Another significant way ride-sharing apps avoid taxi medallion legislation is by not picking people up from the street. You have to hail them using an app. This ends up being a feature, rather than a constraint. First, it’s safer for the driver and the passenger because the transaction isn’t anonymous. Second, it’s more reliable than a taxi dispatched by a cab company. We spoke to InstantCab CEO Aarjav Trivedi to understand why:

Cab drivers don’t have to listen to cab company dispatch and rarely do. If they see people with their bags that look like they’re going to the airport by the side of the road, they will ditch the dispatched call and pick up the street hail. They have no reason to be accountable to the cab company, which in turn has no reason to be accountable to customers because the company makes practically all their money by leasing cabs and medallions to drivers. That’s why taxis dispatched by cab companies don’t show up when you call them.

InstantCab is in an interesting position because they have taxis and community drivers in their fleet. However, if a taxi driver bails on an InstantCab customer to pick up someone on the street instead, they get booted from the service. InstantCab has to artificially add this constraint to taxi drivers, otherwise its service wouldn’t work for the customer.

Finally, these apps can use technology to help drivers optimize their earnings. Taxi drivers maximize profit by knowing where the demand will be depending on the time of day and timing where they look for fares accordingly. Over time, some drivers develop an intuition about this. Ride sharing apps have the data to formalize and optimize this learning.

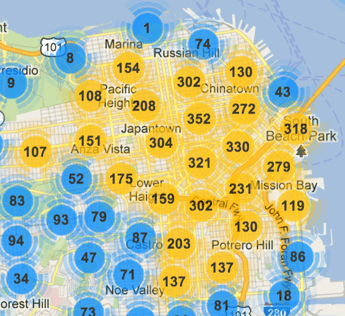

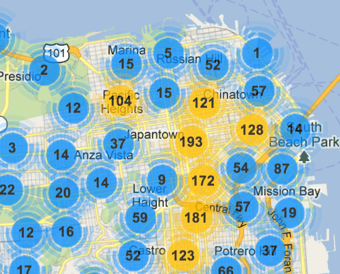

InstantCab was nice enough to share some of this pickup data to illustrate what kind of knowledge about demand matters. The below charts show where in San Francisco they get pickup requests on an average Friday night. We’ve indexed the results to 100 to keep InstantCab’s actual number of requests private. High demand zones (over 100 pickup requests) are in yellow and low demand zones (less than 100 pickup requests) are in blue.

Between 4 pm and 7 pm as people get off work on a Friday, the high demand zones are mostly around “work” areas.

Past 7 pm, as people head out to dinner and bars, the “hot” area expands to include most residential neighborhoods.

Past midnight, as people head home from bars, the requests are mostly along the bar heavy thoroughfares of the city.

This macro view might seem kind of obvious. Sure, after work taxis should be downtown, during dinner time they should be where people live, and late at night they should be at the clubs. A driver might build this intuition on their own after a few days. But in a world without data, it would take a taxi driver years to know exactly where in these high demand zones they need to be and when they should be there. If it’s 5 pm should they be in front of JP Morgan or Zynga? If it’s midnight should they be at Ruby Skye or Circa? Mastering these skills takes years and is a requirement to making a good living as a taxi driver.

How popular are these apps? In San Francisco, where most of them started, there are only 1600 taxi medallions. That means that there are only 1600 taxis on the road at any given time. A vast majority of these licensed taxi drivers have adopted apps. InstantCab alone has over 800 licensed taxi drivers using their app, not including ride-share drivers. According to publicly available statements from ride-sharing companies, there is strong evidence that there are already more community drivers on the road than regular taxis in San Francisco.

In San Francisco, the transformation from a medallion constrained taxi system to a free market is nearly complete. These ride-sharing companies are all rapidly expanding across the country.

The Winners and Losers of Disruption

If this post-medallion system is allowed to flourish, the medallion holders and dispatchers will be out of business.

The value of a medallion drops to almost zero because anyone can be a community driver without one. The extent to which they retain any value is the extent to which drunk people continue stumbling out of bars and hailing a cab without using their phones. So, medallion holders speculated in holding a government asset and lost. Some of these people are also taxi drivers or operators of taxi dispatch companies. Like Greek bondholders, they gambled and lost big.

The middleman in this current system, the taxi dispatch company, will be eviscerated. The software of Uber, Sidecar, Lyft, and InstantCab dispatches rides to customers, the app companies provide insurance, and the drivers provide their own car maintenance. We doubt that the dispatchers will be missed. They have the power to mistreat drivers, and it seems like they exercise that power freely.

Taxi drivers working for these apps reap a number of benefits. They no longer get nailed with opaque fees or start the day hundreds of dollars in debt, so they can start making money the second they start driving. Picking up customers now that cabbies have their credit cards on file is safer because they have a record of everyone entering their taxis. Finally, they are so far making more money per hour than under the medallion system. Most ride-sharing app companies advertise that you can make $20-$30 per hour, which is much better than the current ~$10 an hour taxi drivers make.

So are taxi drivers better off in a liberated, medallion free system? It depends. They will face more competition because anyone can become a taxi driver.

Despite increased competition, however, taxi drivers might thrive in a new world where fees are less onerous. Aarjav Trivedi of InstantCab points out another nuance that helps cab drivers:

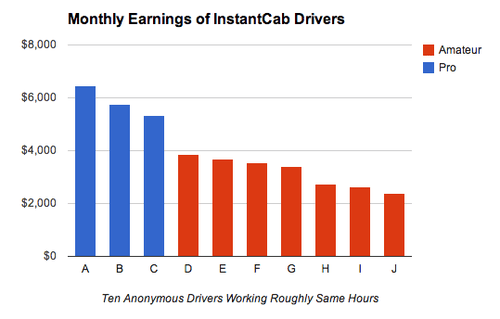

Drivers are in two camps. The Opportunist who is doing it for extra money and the Pro who has been doing it day in day out for years, perhaps because of their experience as a professional driver.

The Pro always wins: they can pick up and drop off customers faster, do a lot more runs, and get paid more. Their knowledge and intuition have evolved to remember how to navigate streets better and where demand is going to be at a certain time.

The Pro also gets significantly higher tips. The best drivers have mastered the basics of customer service: quick pickups, reading cues to figure out whether the customer would like to check their email in quiet or chat about the Giants game, and getting the customer there fast.

Aarjav of InstantCab went so far as to provide us with the actual earnings of drivers that use his company’s app. Below is the monthly take home income of ten drivers that drive in the InstantCab fleet. All ten of the drivers started at InstantCab at roughly the same time and drive nearly the same number of hours per month. Three of the drivers were professionals, and seven were amateurs:

This is the chart that taxi drivers need to think about. Professional drivers are slaughtering amateur community drivers in terms of take home pay. The drivers that know what they’re doing (professionals) and can afford to buy or lease their owns cars may be able to make a very good living under this system. The opportunists might not.

What should taxi drivers do to ride out this disruption? The best bet is probably to try out a few shifts on a ride-sharing app. They can drive around on Lyft or Sidecar with their personal car or on InstantCab with either their taxi or personal car and see what happens.

If drivers find they like getting customers from ride-sharing apps and can make more money, it’s time to leave the sinking ship of the medallion-based taxi economy. If they find they make less money, it’s probably in taxi drivers’ best interests to join medallion-holders and taxi companies in their pursuit to block ride-sharing apps from spreading across America.

Conclusion: What will the government do?

“These medallions are public assets. The value belongs to the people of San Francisco for the benefit of the transportation system.”

– Ed Reiskin, San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Director

“I really hope we keep the medallion system and get rid of ride-sharing apps.”

– No one who uses San Francisco Municipal Transportation, ever

It seems like it’s a safe bet that no one who uses mass transport in San Francisco actually considers medallions to be a public asset. The people who view medallions as a public asset are the beneficiaries of the current system: medallion holders, taxi companies insulated from competition, and, most likely, public officials whose job it is to dole out medallions.

A public asset is safe, efficient transportation, not a scarcity of taxis. Medallions were created in the 1930s to make sure taxis were safe. Regulation of the ridesharing industry needs to focus on safety by making it easy to run background checks on drivers and report driver reviews and incidents to municipal authorities. Right now, all the startups are very focused on having safe drivers because they’re under public scrutiny. But ten years from now, less scrupulous companies may emerge.

The second area where government can help is by protecting drivers from platform lock-in. Right now drivers can only work for one ride-sharing app. The company you drive for is responsible for 100% of your earnings – a level of control that could be abused. If regulators want to help consumers and drivers, they should mandate that a driver cannot be locked into one ride-sharing platform. A driver should be able to freely get a pickup call from Sidecar, Lyft or whomever. More competition between the ridesharing apps is good for drivers and good for consumers.

It seems as if taxi medallion holders and taxi dispatch companies will get wiped out. If local governments step in and ban ridesharing apps, it will be to protect these interests at everyone else’s expense. So far, it seems like that’s what local governments are doing: banning ride sharing apps.

Those that benefit from the taxi medallion system have been protected for 80 years. In that time, they abused taxi drivers and produced a crappy product. Ride-sharing apps should be allowed to take over the market – until they too are disrupted by self-driving cars. And so it goes.

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter here or Google. Special thanks to Aarjav of InstantCab for sharing some awesome data with us.