![]()

Imagine you’ve been convicted of a terrible crime, and are given the chance to speak for a few minutes before your execution. Would you express anger? Remorse? Love?

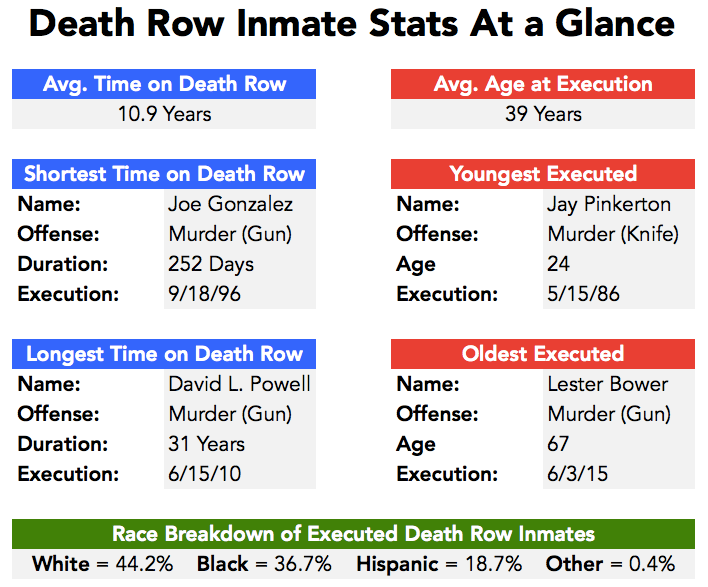

Each year, an average of 35 death row inmates are executed throughout the United States — most by lethal injection. Just before the Pentobarbital is pumped into their bloodstream, they are given the opportunity to provide a final statement (or, colloquially, “last words”). The typical death row inmate spends nearly 11 years waiting for an execution date: there is plenty of time to ruminate and plan a speech. So, what exactly do they choose to say?

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice, which, incidentally, carries out about 5x more executions than any other state, maintains a digital archive of every inmate’s last statement, going back to 1976. This amounts to 534 prisoners, or 37% of all executions in the United States in the last 40 years.

Zachary Crockett; data via Texas Department of Criminal Justice, and includes only inmates executed in Texas

These are men who have been found guilty of atrocious crimes: stabbing victims to death, shooting children, raping and murdering multiple women. They are also men who have nothing to lose. Their death, barring exoneration, is imminent — and whatever they choose to say will have no effect on their legal predicament. Somewhat surprisingly, a large percentage of them use this freedom to express love and sorrow.

We analyzed these statements for common words and patterns (omitting, of course, conjunctions, prepositions, pronouns, and other insignificant terms). Of 534 total inmates, 117 declined to speak; the data we’ll include here pertains to the other 417 inmates, who either spoke or wrote out a final statement.

The chart below shows the 50 words that were used the most by inmates in their final statements, ranked by the percentage of inmates who use each word.

Zachary Crockett; data via Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Used by 63% of all speakers, “love” is the most common word in death row inmates’ last statements. At 689 total instances, that works out to an average of 1.7 times per inmate. Other words that insinuate affection — “heart” (14%), “care” (11%), “loved” (10%) — also rank high on this list.

In most cases, the word is used to address family members who are present at the execution, on the other side of the glass window. But it is also used to express feelings toward the victim’s family members, lawyers, the court, and even the warden/prison staff. We’ve picked out a few of these excerpts:

Zachary Crockett; data via Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Despite their callous criminal histories, death row inmates seem to have particularly good manners: last statements contain high rates of the phrase “thank you” (34%), as well as the words “sorry” (29%) and “please” (8%).

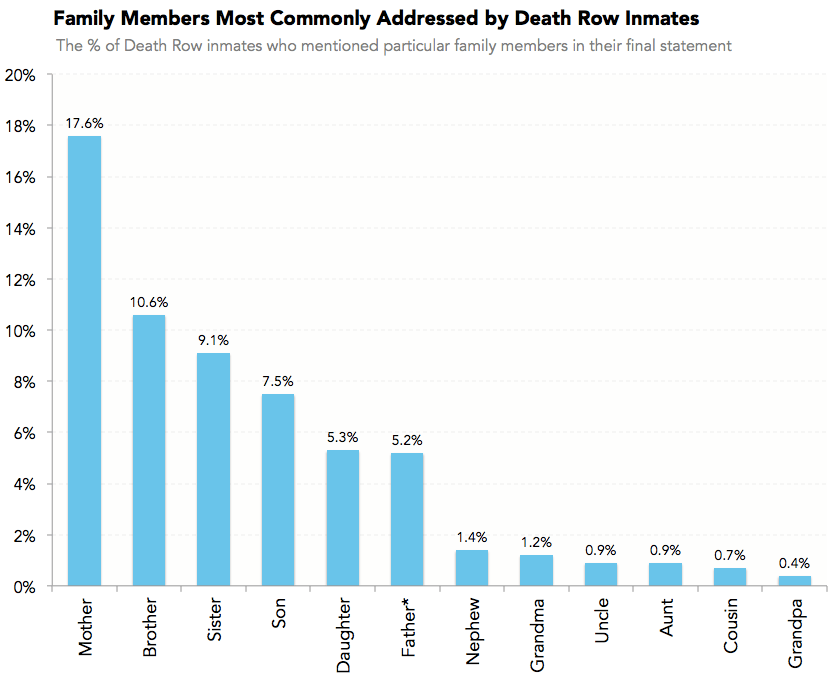

After love, the word “family” ranks second, included in 45% of all last statements. But it seems that inmates don’t appreciate all family members equally. We searched through the statements, compiling all mentions of kin, then combined all variations (ie. “mama”, “mom”, and “ma” were included as “mother”). The following chart breaks down the frequency at which each family member is mentioned:

Zachary Crockett; data via Texas Department of Criminal Justice

In their final statements, inmates express the most gratitude and sorrow to their mothers. This isn’t too surprising: studies have shown that nearly all death row inmates “have a history of parental abandonment, foster care and/or institutionalization.” Typically, the mother is more present than the father in their lives.

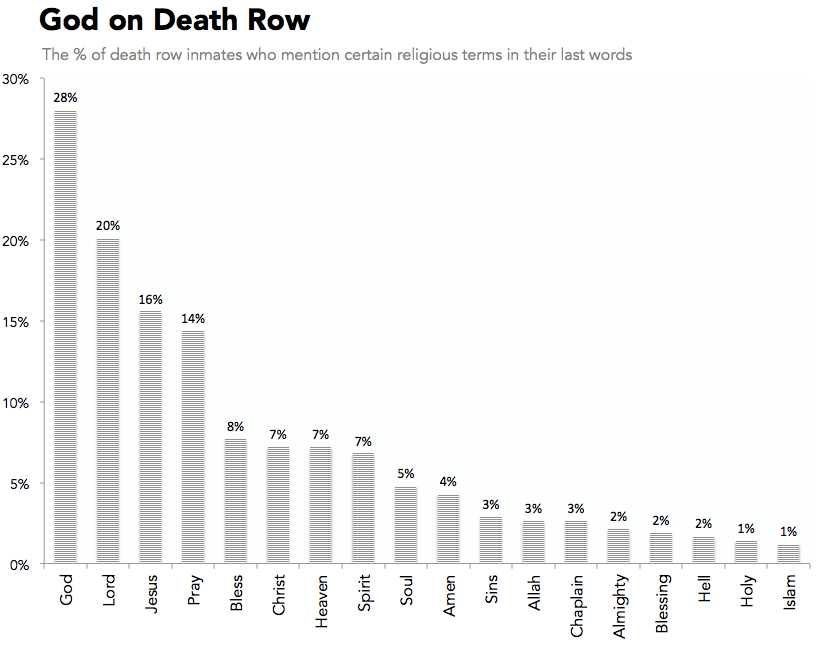

While nearly 11% of all inmates use the word “father”, only around 5% are actually in reference to a father figure. Far more commonly, it is used to refer to God — most often, as part of The Lord’s Prayer (“Our Father, who art in heaven…”).

Nearly 30% of all executed inmates express religious thoughts. In most instances, they ask for repentance, forgiveness, and acceptance into heaven.

Zachary Crockett; data via Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Religious conversion is so common in prison (especially on death row), that a term exists to describe it: Jailhouse Jesus. A chaplain roams the corridors, often offering the only visage of hope for prisoners, who are often alienated and in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day. Salvation is pitched as a way to transcend these poor conditions, and repent for sins.

Others devote their final words to maintaining innocence.

While roughly 29% of inmates express sorrow and/or forgiveness for their crimes, 10% of inmates use their final statement as an opportunity to deny the charges against them. It is entirely possible that some of these men actually are innocent: a University of Michigan study confirmed that 1.6% of all death row inmates have been exonerated since 1973, and another study “conservatively estimates” that 4.1% of all current inmates on death row are innocent.

That said, there seem to be considerably more inmates professing innocence than is statistically likely (at least, according to the aforementioned research). We’ve included a few examples of these statements below.

Zachary Crockett; data via Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Inmates also occasionally use their last words to make a political statement about prison conditions or the death penalty. Gary Graham, who was executed for killing a man over $100, had this to say:

“I’m an innocent black man that is being murdered. This is a lynching that is happening in America tonight. What is happening here is an outrage for any civilized country to anybody anywhere to look at what’s happening here is wrong. You are pursuing the execution of an innocent man. We must stop the systematic killing of poor and innocent black people. We must continue to stand together in unity and to demand a moratorium on all executions. We must not let this murder/lynching be forgotten tonight, my brothers.

Slavery couldn’t stop us. The lynching couldn’t stop us in the south. This lynching will not stop us tonight. We will go forward. You can kill a revolutionary, but you cannot stop the revolution. The revolution will go on. We will prevail. We will keep marching. Keep marching black people, black power. Keep marching black people, black power. Keep marching black people. Keep marching black people. They are killing me tonight. They are murdering me tonight.”

Considering the long history of the last statement, this approach is not that unusual.

According to law scholar Kevin O’Neill, the right of a prisoner to speak before an execution spans back at least 500 years — and since the practice has traditionally been free from censorship, prisoners have always freely expressed their opinions.

“The privilege was extended to everyone: from kings, queens, and aristocrats, to the lowest of the low — even to prisoners of war and…the assassins of Presidents Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley,” he writes. “[Many] turned political, criticizing the death penalty, excoriating the justice system, or expressing solidarity with a movement or cause.”

Many inmates — both in the present day, and historically — used their last words to make a political statement, including President Garfield’s killer, Charles Julius Guiteau

For instance, Charles Julius Guiteau, who was executed in 1882 for killing President Garfield, famously proclaimed: “This nation will go down in blood…My murderers, from the Executive to the hangman, will go to hell.”‘

Of course, not every inmate speaks his or her mind. Of the 534 death row executions we looked at, 117 (22%) chose not to speak at all. It is impossible to determine whether they did so out of spite, fear, respect, or apathy.

Regardless of what an inmate chooses to express , the final statement is an important tradition to maintain. As one man said, while tied down on the lethal injection gurney, “Now that I am dying, I can tell the truth.” Not every inmate does so — but for the considerable majority of them, the final statement is an opportunity to express love and ask for forgiveness.

![]()

In our next post, we take a look at the ever-shortening nature of the pop song title. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter at @zzcrockett