“The report of my death was an exaggeration.”

~ Mark Twain, 1897

![]()

In August of 2010, communications specialist Judy Rivers went to her local bank to open a new account. As the clerk input Rivers’ personal information, everything seemed to be going smoothly — but then the woman behind the desk stopped abruptly and frowned.

“That’s odd,” she said. “There seems to be an issue regarding your Social Security Number.” With a skeptical glance, the employee rose and disappeared in the back room; several minutes later, Rivers was greeted by the branch manager.

“Mam,” the woman pronounced, brandishing a folded paper, “your Social Security Number was deactivated in 2008 due to death.”

Incredulous, Rivers rose from her chair. “You’re trying to tell me I’ve been dead for two years,” she stammered, “and no one bothered to tell me?”

Rivers’ plight as a falsely-categorized deceased person is not singular: it is estimated that every year, some 12,200 very much alive U.S. citizens are declared dead by the Social Security Administration due to “keystroke errors.” Those affected quite literally become a walking dead, unable to secure a job, make financial transactions, file taxes, or visit the doctor — and for months on end, must endure the nightmare of convincing a large bureaucracy that they haven’t yet bit the dust.

***

Created in 1935 as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Social Security Administration is a social insurance program which levies a tax on Americans to provide retirement, disability, and survivors’ benefits for those in need. At birth, most individuals are issued a nine-digit number (Social Security Number, or SSN); while the number’s main purpose is to track Social Security contributions, it has also become a “de facto form of national identification.”

But the Social Security Administration has another task: keeping track of the dead.

Since 1980, it has maintained the Death Master File, a database of more than 86 million deceased, SSN-holding Americans. When you are medically recorded as dead, you are included in this master file and your SSN is retired, disabling any future use; a few weeks later, Medicare, the IRS, law enforcement, and employers essentially “scratch you out of existence.”

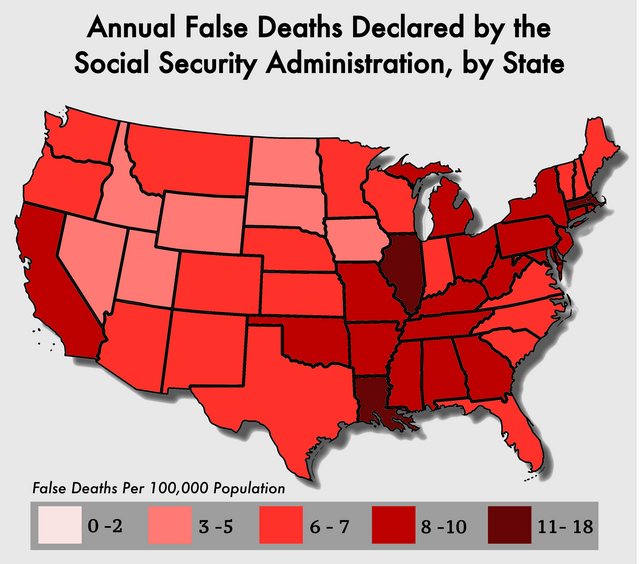

In 2011, the Office of the Inspector General conducted an audit of the Death Master File, and found that, from May 2007 to April 2010, 36,657 living people (12,219 per year) had been prematurely added, nulling them legally dead. After probing deeper, officials estimated that between 700 and 2,800 people were erroneously declared dead every month since the list’s inception. Over the file’s 35-year history, the Inspector General suspects that more than 500,000 Americans have been affected.

Priceonomics; Data via the SSA Death Master File

Most of these, says identity theft expert Steven Weisman, are a result of simple clerical errors.

“They type in a digit wrong on a Social Security Number [called a “keystroke error”] and that is when it starts,” he told CBS News. “Where it is so easy, just a slip of your little finger to kill someone, it’s very difficult to bring someone back to life, and it can be very very frustrating.”

Erroneous death entries, writes the Inspector General in its report, can “lead to benefit termination, cause severe financial hardship and distress to affected individuals.”

Judy Rivers learned this the hard way.

***

In March 2015, seven years after being declared dead via a keystroke error by the Social Security Administration, Judy Rivers stood before the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs and related her story:

“I could never have imagined I would reach the point of hopelessness, homelessness, loss of reputation and credibility, unable to obtain a job, an apartment, a student loan, or even a cell phone. Suspected as an identity thief by nearly every apartment manager or Human Resource Director I encountered became a way of life. Each time I got into my car I was panic stricken that the police would stop me and I would have to try and prove my identity.”

After her bank froze her checking account, Rivers found herself in a state of “financial destitution.” Even so, things could’ve potentially ended up much worse for her: for many in a similar predicament, the consequences of being legally dead are much graver.

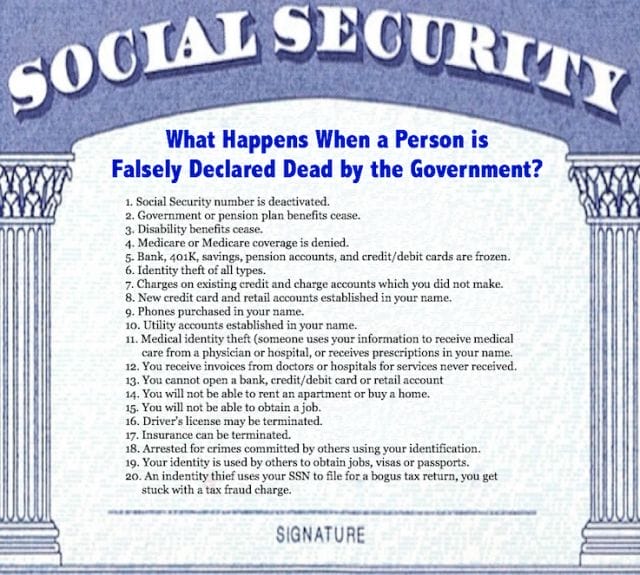

When a person is listed in the Death Master File, his or her personal information — name, birth date, address, Social Security Number — is distributed to “virtually every financial database” in the country. Since the Death Master File is also in the public domain, anyone with Internet access can steal and use your information to “wreak havoc with your finances and your life.”

According to Jay Foley, the former executive director of the Identity Theft Resource Center, the consequences of being a “credit zombie” are wide ranging, and severe:

Priceonomics

He’s heard the stories of hundreds of people falsely declared dead: An 83-year-old woman whose SSA checks were discontinued, and who was unable to purchase vital medications; A man who was fired from his job after a medical thief “left drug addiction and narcotic medications in his records”; A young mother who found out that an identity thief had purchased a $400,000 home using her information.

Patty Young, a 65 year-old New Hampshirite, found out that she was “dead” while attempting to get a new driver’s license at the DMV. Upon consulting her local Social Security Administration office, she’d been “killed” due to a lone typo by an administrator.

“I started to laugh when they told me,” Young told CNN. “I had no idea what a big deal it would become.”

In the past, Inspector General Patrick P. O’Carroll, Jr. has said that when the Social Security Administration becomes aware of a death error, “it moves quickly to correct the situation.” For Young, this was not true.

While she was told the error would be reversed in two business days, it ended up taking three months. During this time, she was left without a driver’s’ license, and her benefit checks were discontinued — but even worse, an identity thief pilfered her SSN from the Death Master File, and used it to file his tax return. As it typically takes the Social Security Administration 4 to 6 weeks to discontinue the SSN of a recently deceased person, identity theft is a common ordeal for living persons who are categorized as dead.

After a funeral director mistyped a SSN in a death notice, fifty-two-year-old, Laura Brooks, also ended up in the Death Master File. She had to wait three months to get reinstated as “living,” during which time she missed out on $1,000 in disability checks, and racked up $400 in bounced check fees. When the Social Security Administration finally reversed her death, it refused to reimburse her for this money.

“Those disability checks were everything I had,” she told a news outlet. “But more than the financial impact of all of this was the psychological shock — it spiraled me into further depression and really started me on the road to questioning authority.”

According to the Social Security Administration’s data, the average benefit check is $1,228 per month. Assuming that the 12,219 people falsely declared dead each year experience an average discontinued check period of 3 months (which seems typical), the federal government wrongly withholds more than $45 million in Social Security benefits every year due to clerical “death” typos.

***

Unfortunately, “credit zombies” are the least of the Social Security Administration’s concerns.

A March 2015 audit found that there are 6.5 million active Social Security card holders who are listed as over the age of 112 — including several thousand who were born before the civil war. In reality, there are only 11 people alive verified to be over the age of 112 in the United States. Essentially, this means that there are 6.5 million errors in the system, leaving the door wide open for identity thieves to use antiquated digits (an active Social Security number can be had for as little as $1 in the crime underworld — cheaper than nearly any illicit drug).

In addition, the report found that thousands of truly deceased individuals were still receiving payments — some as much as 20 years past the date of their death. These payments amount to more than $133,000,000 in taxpayer dollars. “Washington,” writes one journalist, “is bedeviled by both the living dead and the dead living.”

To be fair, the Social Security Administration processes a massive amount of dead people — some 2.8 million per year. Considering this, their annual 12,000 erroneous death declarations amounts to an error rate of less than 1%. Still, when dealing with the legal sensibilities on life and death, these are particularly damaging errors to make — errors that victim Judy Rivers recalls as “insufferable.”

“This computer file has [resulted in] Orwellian nightmares for Americans who have difficulty convincing a data-driven world that they are, in fact, alive,” she told the Senate committee. “No citizen deserves to suffer due to its government’s refusal to correct an administrative problem.”

“It is incredible,” agreed Senator Ron Johnson, “that the Social Security Administration, in 2015, does not have the technical sophistication to ensure [whether or not] people are dead.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.