Spaniards call the European Union’s 500 euro note “the bin laden.” The currency’s existence is well known, like that of the terrorist leader up until his death, but 500 euro notes are hard to find. According to the UK’s Serious Organised Crime Agency, criminal organizations hold 90% of the 500 euro notes in the UK, esteeming them for the ease of hoarding wealth and laundering money in bulk.

Whether in the form of briefcases of $100 bills or a few twenties stolen from a wallet, cash fuels black markets and both petty and organized crime. But money appears to be headed toward a digital future. What happens to crime when the briefcases go away — or are at least less full?

According to six researchers from the National Bureau for Economic Research, the University of Missouri-St.Louis, and Georgia State, the United States has run a sort of natural experiment over the last two decades. States have gradually implemented national legislation that reforms how welfare benefits are distributed. In their paper “Less Cash, Less Crime,” the researchers argue that this reform has reduced the amount of cash held in areas with high rates of street crime, allowing them to investigate the effect of a sudden drop in the availability of physical currency on crime rates.

A strain of law enforcement thinking has sought an end to cash as a means to fight crime. Could it work?

Cash is King

Paper currency is both the motive of many crimes and a facilitator of illegal activity.

Organized crime depends on the relative anonymity and untraceability of money; drug dealing, illegal weapon sales, and other illicit markets all rely heavily on cash transactions. More mundanely, when Spain concluded in 2006 that it was home to one quarter of all 500 euro notes in circulation, leaders speculated that the “bin Ladens” enabled bribery associated with Spain’s (then) booming real estate market and that individuals and businesses were conducting transactions in cash (and off the books) to avoid taxes.

In lower level street crime, criminologists cite acquiring cash to meet immediate needs as the motivation of most criminals. Moreover, the perpetrators of petty crime usually rank among the 43 million “unbanked” Americans who do not have access to financial services like a checking account, and they engage primarily in a cash-based street or underground economy that uses cash either due to its illicit nature (illegal drugs; prostitution) or a lack of access to financial services (street vendors; pawn shops; corner stores).

In other words, cash is oxygen to crime’s flame. So could the end of money extinguish crime?

More Money More Problems

In the eyes of the authors of “Less Cash, Less Crime,” a change in how Americans receive government benefits provides an ideal means to test the relationship between cash and crime.

Through the mid 1990s, welfare recipients received monthly benefits in the form of paper checks. Mailed at the beginning of every month, it resulted in a “first of the month economy,” with long lines at discount retailers and liquor stores as people spent their new cash.

Since many welfare recipients are unbanked, the first of the month also saw long lines at stores that offered check cashing services. This meant that welfare provided a monthly injection of paper currency into poor communities where the majority of petty crime takes place, and a fresh supply of victims for criminals to target.

Federal legislation in the 1990s mandated that Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) cards, which resemble debit cards, replace checks as the means for doling out benefits. Recipients of welfare (or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance System and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families programs) can still withdraw cash using EBT cards, but they can also use EBT cards at participating stores. The end result — the authors believe — is a decrease in the amount of available cash.

Although the result of national legislation, the federal government left it to the states to enact the change, which many did on a county by county basis. This allowed the researchers to compare crime rates in counties that implemented the reforms with those that had not.

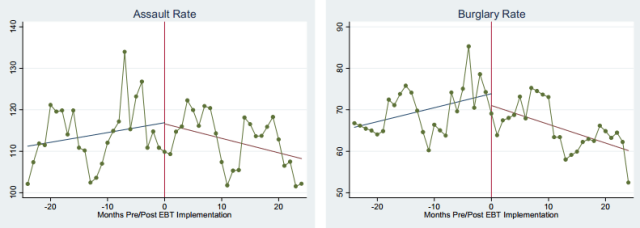

The researchers chose the case of Missouri. Drawing on data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, they compared how the crime rate changed before and after the reform to how it changed in counties without the reform. They hypothesized that they would find a reduction in the rate of financially motivated street crimes like muggings. The study’s authors also expected to see a drop in crimes like assault, which do not necessarily involve financial gain, but go hand in hand with financially motivated crimes — whether that’s organized crime striking at a rival or an individual getting revenge on a thief. In contrast, a crime like rape that is usually unrelated to financial concerns should see no effect.

Source: “Less Cash, Less Crime.” NBER working paper. Rates refer to crimes per 100,000 population.

The researchers conducted a statistical analysis, which found a clear negative correlation between crime and the use of EBT cards. That relationship is represented visually in the included graphs. (Although their results are still a working paper, meaning they are inviting feedback before going through peer review and publishing the results.)

Source: “Less Cash, Less Crime.” NBER working paper. Rates refer to crimes per 100,000 population.

As expected, rape is an exception. And while not a perfect relationship, almost every category of relevant crime sees a reduction.

While the study contains more nuance, the authors write that “by removing something less than $55.9 million in cash from circulation each month, we estimate that EBT achieved a nearly 10% decrease in the crime rate.”

From Benjamins to Bytes

“To put it in succinct and current terms, money’s destiny is to become digital.”

~OECD report on The Future of Money

Futurists have long imagined paying for everything digitally — or through chips implanted in our skin — and some banks are already preparing for virtual currencies like Facebook cash or the digital currency Bitcoin.

The demise of cash may not seem imminent, but its use has declined dramatically. The authors of “Less Cash, Less Crime” note that credit cards, debit cards, and mobile transactions have conspired to decrease the prevalence of cash transactions in America from 80% of payments to around 50%. They also cite a 2012 study that found that cash volume has grown at a rate of 4% since 1990 compared to a 2,700% growth in debit transactions and a decline of 50% in the use of checks.

The $2 trillion underground economy, however, doesn’t seem ready to part with cash. In fact, there is some evidence that the money supply is growing. A 2002 International Monetary Fund column cites the amount of paper currency held by the public as over “$620 billion, or roughly $2,200 for every man, woman, and child.” An article published by economist Reza Varjavand in 2011 claims that number rose to $3,000 as part of a long term trend of increased demand for cash.

Bartering is the New Black

“In terms of public safety and national security,” Jonathan Lipow, an economist at the Naval Postgraduate Institute writes, “the sooner the world moves to a digital cashless economy, the better.”

The U.S. government did not implement EBT cards as a crime fighting measure. But if all money goes digital, either as the result of economic forces or of law enforcement efforts, how would it affect black markets?

Rather than ending crime, it may make crime yet another field where a college degree is a prerequisite. As Richard Wright and Volkan Topalli point out in the Oxford Handbook of Criminology Theory, petty thieves struggle, for example, to make efficient use of stolen debit cards. In contrast, the transition to electronic payments will continue to benefit criminals with the education and means to steal account passwords, and white collar crime will only be marginally affected. They write:

The move to alternative forms of monetary transfer will likely shift the distribution of criminal opportunities from the street to the suite, with a majority of crime in the next century available only to those with an education, an intimate knowledge of technology, and the capital to invest in criminal schemes meant to access the “new economy.” If that happens, the rich will have usurped pretty much everything from the urban poor, including realistic access to predatory criminal opportunities.

Nothing demonstrates this better than the digital marketplace Silk Road. Thanks to the anonymity of Tor software and the digital currency Bitcoin, users bought and sold over $1 billion worth of product that included marijuana, cocaine, and handguns before the FBI arrested its “mastermind” Ross Ulbricht. Copycat Silk Road websites have since been launched.

It remains to be seen whether Bitcoin, a currency which uses encryption to give transactions the anonymity of cash, yet also publicly records each and every transaction, will enable black markets. (For a full primer on Bitcoin, see our article.) And as long as we’re speculating, a cryptocurrency could gain wide enough adoption that it replaces much of the role played by cash in the underground economy for street crime as well.

Seven to ten percent of American households, however, lack access to basic financial services like a checking account due to either an inability to meet requirements such as a minimum balance or permanent address, a lack of education, or a lack of legal status. This not only speaks to why better educated criminals will benefit from a move away from paper currency while street criminals struggle. It also shows how it would hurt more legitimate aspects of the informal economy ranging from under-the-table payments for undocumented workers to small businesses that don’t declare their existence to the IRS.

That said, the underground economy already uses a surprising amount of bartering that helps immunize it from a lack of cash or financial services.

Petty thieves are well aware of the inefficiencies of bartering. A criminology study that interviewed “prolific thieves” found that burglars know exactly where they will sell their loot; they take goods to people known to fence them within a few minutes of the crime, and they dislike bartering stolen goods because they know they will not get as good a deal.

Yet bartering already thrives in street crime. A story in last year’s New York Magazine described how thieves steal Tide Detergent to buy drugs, with one Safeway store losing $10,000 to $15,000 of detergent a month. As we related in a blog post, thieves target common, cheap goods like bars of soap, razors, and cigarettes because their ubiquity and stable demand means that they are as good as stealing cash (it’s always easy to sell stolen soap since everyone uses it) and can be used as currency.

Our investigation of stolen bikes also revealed a surprising aspect of the street barter economy. As Sgt. Joe McKolsky, a bike theft specialist for the SFPD, notes, “Bikes are one of the four commodities of the street — cash, drugs, sex, and bikes… You can virtually exchange one for another.”

Crime and cash go hand in hand, and a decline in the prevalence of paper currency could lead to a reduction in crime rates. But like with Communism, the end of cash sounds best in theory. Don’t expect it to lead to a utopia.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.