When the Michelin Guide comes out each year, foodies freak out.

Michelin’s food critics, known as “inspectors” by the company, only awarded a top ranking of three Michelin Stars to around 100 restaurants in 2016. Restaurants that receive a Michelin Star for the first time can expect a flood of food tourists; losing a Michelin Star devastates restaurateurs. Gordon Ramsay, the celebrity chef who makes young chefs weep on his show Hell’s Kitchen, cried when he lost two Michelin Stars in 2013.

Which is a bit weird, because Michelin is a tire company whose annual reports highlight the cost of rubber and growth in the passenger car market.

Michelin began publishing its “Red Guide” in 1900, when both cars and food tourism were novel luxuries. Its creators hoped that a guidebook offering information about hotels, restaurants, and roadways would lead people to drive more—and buy more Michelin tires.

Today, Michelin continues to authoritatively judge restaurants in order to promote the company name. It’s a bit like if the Coca-Cola Company ran the Oscars, having created the ceremony in the 1920s so that people would go to the movies and drink more soda. It’s debatable whether the guide still helps Michelin sell tires, but Michelin’s ownership has been instrumental to the renown and authority of its restaurant guides.

If the Michelin Guide wasn’t a marketing expense for an unrelated, major corporation, it may never have become the final word on culinary perfection.

Creating a Market

There once was a time when people had to be convinced that a car was useful. That was the situation in 1895, when brothers Edouard and Andre Michelin developed a new design for a car tire at their rubber company in Clermont-Ferrand, France.

The brothers had a superior product: one of the first air-filled tires, which could be quickly replaced since it was not glued to the wheel. To prove its value, the brothers sponsored car races, which drivers with Michelin tires often won handedly.

But France had only around 350 cars in 1895. Automobiles “remained rich men’s toys… unable to stray very far from the vicinity of a reliable repair show,” Herbert Lottman writes in The Michelin Men. “The nascent motorcar could easily be dismissed by seasoned entrepreneurs on the lookout for realistic investments.”

In this environment, increasing the number of drivers—the motivation for the Michelin Guide—was more important than gaining an advantage over other tire manufacturers.

First published in 1900, the guide’s 399 pages contained all the information drivers needed to “go touring” through French towns and cities. Only restaurants attached to hotels were included, and they were listed rather than carefully rated. Information about installing and caring for Michelin tires occupied the first 33 pages, and ads for car part manufacturers occupied another 50 pages. Maps and basic information about dozens of towns made up the bulk of the guide.

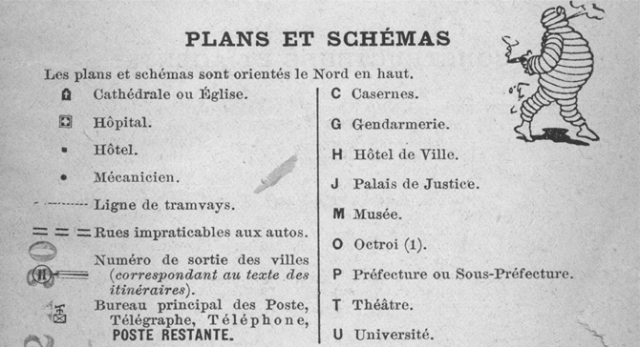

A legend for a map in an early Michelin Guide, with the Michelin Man smoking in the corner. (It was a different time.) Image via “Maps for a New Kind of Tourist: The First Guides Michelin France” by Kory Olson in Imago Mundi.

For drivers, that information was essential. Gas stations did not yet exist, so drivers needed to know which pharmacies sold gasoline in several-liter containers. Motorists needed the timetables that listed when the sun set during the year, because highways did not yet have lights. Only a fraction of auto repair shops stayed open all year, which made it crucial to know which closed at the end of summer. Details like this distinguished the Michelin Guide from the tour books of the time, which assumed that people traveled by rail.

The Michelin brothers’ efforts to make driving easier extended beyond the guide. Once company employees began rating hotels, they made clear to hoteliers that they should offer free parking. They also lobbied the government to put up road signs for motorists—Edouard Michelin is sometimes credited with inventing road numbers, because he convinced the government to enlarge the numbers it painted on highway posts. At times, company men put up road signs themselves.

Similarly, a major aim of Michelin marketing was to promote the car as a way of life. “With a car, no more 5 a.m trains,” a Michelin ad in 1924 declared. “With a car, there is more opportunity for the pleasant things in family life.”

“Our industry is directly interested in the continual progress of automobiles, on which it depends,” Michelin once wrote in an article. In creating the guide, the brothers hoped to provide the information and infrastructure that would convince rich people to buy cars, drive throughout France, and buy Michelin tires.

Even if that meant creating an entire guidebook side-business to do it.

“Worth the Trip”

The Michelin brothers were not modest men. In 1900, in the introduction to the first Michelin Guide, Andre proclaimed, “This work comes out with the century; it will last as long.”

Predicting that its promotional guidebook would endure for 100 years was bold. Yet, remarkably, it was an underestimate.

Michelin distributed tens of thousands of complimentary copies in 1900. But when the company began charging around $2 for the guide in 1920, it still sold nearly 100,000 copies a year. As of 1953, its loyal readership submitted 50,000 comments to improve the guide’s accuracy. Some wrote every week.

During this period, the focus on tire maintenance gave way to classic guidebook fare. In 1926, Michelin created regional guides, later known as Green Guides, which resemble Lonely Planet and traditional travel guides. Meanwhile, the Red Guide, in response to reader interest, focused on reviews of hotels and restaurants, with separate guides for different areas and cities. The company hired full-time critics, known as inspectors, to spend months on the road judging the best restaurants. Good restaurants received recognition in the guide; exemplary ones received from one Michelin Star (“a very good restaurant in its category”) to three Michelin Stars (“one of the best, worth the trip”).

By the 1930s, the Red Guides enjoyed international renown. The New Yorker sang its praises, and forgave the tire ads sprinkled throughout because they were done “gaily and unobtrusively!” In 1952, TIME Magazine called it the “tourist’s Bible”, and a celebrated French chef stated that “there is only one guide in France, the Michelin.” Today, 116 years after the first edition, Michelin still publishes the Red Guide to great fanfare.

So how did a tire company become—and why does it remain—the arbiter of culinary greatness?

One prerequisite is the longevity of the Michelin tire company, which is a remarkable story in itself. The family company weathered world wars and a century of booms and busts to become one of the world’s largest tire companies. (The 1945 guide lamented how many “good [French] cooks sit in German prison camps waiting for return to their ovens.”)

The 30-year tenure of the Michelin brothers was a partnership between Edouard, an engineer credited with important advances in tire technology, and Andre, a marketing genius. In addition to the guide, Andre paid newspapers to run columns describing the spread of his magnificent pneumatic tires, deftly played to French nationalism (Michelin competed in a promotional road race in Germany, the company reassured French readers, to beat the Germans), created a community by positioning Michelin as in the service of motorists and their cause, and invented the Michelin Man, the instantly-recognizable stack-of-tires mascot that is now on the Madison Avenue Advertising Walk of Fame.

Andre’s background as a government cartographer also helped: He spent seven years developing some of the world’s best maps, and on D-Day, Allied troops famously arrived in Normandy with Michelin Guides because of their quality. And so did the fact that Michelin is a French company.

More importantly, the Michelin Guide restaurant reviews could be shamelessly elitist because the tire customers targeted by Michelin in 1900 were the elite. The Michelin Man looks like a marshmallow today, but when he was created, cars were toys for the rich, and he looked like Michelin customers: He chomped on a cigar, held a champagne flute, and wore a pince-nez.

A normal restaurant guide could never have maintained such selective standards that it only awarded stars to a few dozen (or just a few) restaurants in an entire country. The market of interested people would be too small to cover its costs. The Michelin Guide, however, initially only cared about an elite who’d want to know about the 12 best restaurants in France, and its editors could count on the Michelin marketing department covering its costs.

A 1898 poster for the Michelin Man in his original incarnation as an upper class man. His champagne flute contains broken glass to represent how Michelin’s air-filled tires “drink up obstacles.” Photograph via TM: The Untold Story Behind 29 Classic Logos.

The Michelin Guide “is unique among commercial guidebooks,” a journalist observed in 1954, “in that it makes a virtue of losing money, and by doing so at the rate of some tens of thousands of dollars a year, it has achieved a reputation for thoroughness, discrimination, and incorruptibility that is also unique.” This is especially true now that no one needs to buy the Michelin Guide, since they can read the list of Michelin Star restaurants on a food blog.

The Michelin Guide has been criticized for not employing enough inspectors to authoritatively judge the areas it covers. But when a typical travel guide awards a restaurant four stars, that usually means an employee quickly visited several years ago, and someone recently spent five minutes making sure it still exists. Or, as is the case with Zagat, it relies on customer reviews and surveys.

You may believe in the Yelp model, but most millionaires and world renowned chefs do not. Only Michelin can afford to send eight inspectors to a restaurant in a year when deciding whether to give it a third star—inspectors who remain secret rather than ask for free meals, and who (the few accounts of journalists accompanying inspectors make clear) identify each ingredient and do things like furrow their brow and say, “It is a question of grave importance whether it deserves its three stars.”

Expending resources like that is a foodie’s dream. But only a company indifferent to monetization could achieve it.

Does the Michelin Guide Help Michelin?

The Michelin brothers’ goal with the Michelin Guide—securing the future of the automobile—was achieved decades ago. Yet the tire company keeps printing its Red and Green guides.

That is partly because selling Michelin maps and travel guidebooks—although not its red restaurant guides—became quite profitable. Travel guidebooks were good businesses throughout the 20th century, and in 2007, the BBC bought the Lonely Planet for $207 million. It wasn’t until 2008 that the twin blows of the Great Recession and online competition hammered the guidebook’s business model. In 2012, Michelin’s Senior Vice President for Communication and Brands told Ad Age, “We are trying to adapt to this new digital and free-content environment.” A spokesperson for Michelin North America says the company, like its competitors, is releasing travel apps and doing better than you might expect.

But Michelin is a tire company. If the only reason for the guide’s continued existence was profits, Michelin likely would have sold the guidebook business, and it wouldn’t keep subsidizing the restaurant guides.

Instead Michelin’s maps, guidebooks, and restaurant reviews are promotional—as evidenced by the company’s head marketer retaining responsibility for them. Tourism and Michelin Stars are rarely mentioned in the company’s financial documents or investor presentations. We could not confirm with Michelin whether its maps and guides are profitable, but Tony Fouladpour, a spokesperson for Michelin Travel and Leisure in North America, tellingly did not know if his division’s products made money. “It’s considered an investment really,” he says.

So is it a good investment?

According to Natalie Mizik, Professor of Marketing at the University of Washington, the value in running a promotional effort lies in connecting the core business to “the perception that this is what the company is about.” It’s generally a good strategy, as customers transfer associations from the promotional efforts to the brand. This is why Red Bull, the makers of an energy drink, sponsor extreme sports and host live events on Red Bull TV. And it’s why Michelin’s travel guidebooks, as well as its newer GPS services, have an important promotional value for Michelin, a company associated with travel know-how.

“Maps and guides are a way to have proximity to the consumer,” Michelin’s head marketer told Ad Age in 2012. “You buy a tire every two years, so your proximity with the brand isn’t so frequent. But these guides come out once a year, and they can be used regularly. It’s a very agreeable way to interact with the brand.” Dr. Vicky Lane, an Associate Professor of Marketing at University of Colorado Denver, sees Michelin’s guides as a pioneering example of content marketing, a contemporary buzzword among businesses hoping to attract customers and promote their brand with popular articles, videos, or other media.

Yet it’s less clear whether this is true of the renowned restaurant guide. “I think this is one of the more unusual cases,” says Dr. Mizik. “If there is no perceived link, there would be no effect.”

Michelin executives clearly believe the association between the company and Michelin Stars is helpful; this year, the company acquired Book a Table, the European equivalent of OpenTable, to complement its online restaurant search service. Michelin tires are a premium brand; perhaps being an authority of fine dining helps legitimize the higher price point of its tires.

Dr. Lane says her research shows that even unrelated content can help a brand’s core business, and that Michelin is a fantastic example of this. But she concedes that conclusions on this point are more ambiguous, with most experts advising against producing unrelated services or content to promote a brand.

It’s easy to see why. Dr. Mizik is a marketing professional, and she confessed to not knowing the connection between Michelin tires and the restaurant guides. Spokesperson Tony Fouladpour says this is common. “You’d be surprised how many people don’t know,” he says. “All the time, people tell us, ‘We didn’t know it’s the same company!’”

This is not the debate people usually have over the Michelin restaurant guide. Instead people either follow its recommendations and greet its publication with excitement—or attack the guide for its stuffy, French standards and the crowds of food snobs it unleashes.

Yet it’s this debate over brand promotion and content marketing that will ultimately decide the fate of Michelin Stars and the world’s most celebrated culinary guide. Because if a group of marketers and executives decide that it no longer helps Michelin sell tires, the Michelin Guide—or the unusual circumstances that have allowed it to thrive—could disappear.

Our next article is a data-driven look at the connection between a city’s African-American population and the use of fines as a government revenue source. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Want to write for Priceonomics? We are looking for freelance contributors.