Scientists’ work follows a consistent pattern. They apply for grants, perform their research, and publish the results in a journal. The process is so routine it almost seems inevitable. But what if it’s not the best way to do science?

Although the act of publishing seems to entail sharing your research with the world, most published papers sit behind paywalls. The journals that publish them charge thousands of dollars per subscription, putting access out of reach to all but the most minted universities. Subscription costs have risen dramatically over the past generation. According to critics of the publishers, those increases are the result of the consolidation of journals by private companies who unduly profit off their market share of scientific knowledge.

When we investigated these alleged scrooges of the science world, we discovered that, for their opponents, the battle against this parasitic profiting is only one part of the scientific process that needs to be fixed.

Advocates of “open science” argue that the current model of science, developed in the 1600s, needs to change and take full advantage of the Internet to share research and collaborate in the discovery making process. When the entire scientific community can connect instantly online, they argue, there is simply no reason for research teams to work in silos and share their findings according to the publishing schedules of journals.

Subscriptions limit access to scientific knowledge. And when careers are made and tenures earned by publishing in prestigious journals, then sharing datasets, collaborating with other scientists, and crowdsourcing difficult problems are all disincentivized. Following 17th century practices, open science advocates insist, limits the progress of science in the 21st.

The Creation of Academic Journals

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” ~ Isaac Newton

Into the 17th century, scientists often kept their discoveries secret. Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz argued over which of them first invented calculus because Isaac Newton did not publish his invention for decades. Robert Hooke, Leonardo da Vinci, and Galileo Galilei published only encoded messages proving their discoveries. Scientists gained little by sharing their research other than claiming their spot in history. As a result, they preferred to keep their discoveries secret and build off their findings, only revealing how to decode their message when the next man or woman made the same discovery.

Public funding of research and its distribution in scholarly journals began at this time. Wealthy patrons pooled their money to create scientific academies like England’s Royal Society and the French Academy of Sciences, allowing scientists to pursue their research in a stable, funded environment. By subsidizing research, they hoped to aid its creation and dissemination for society’s benefit.

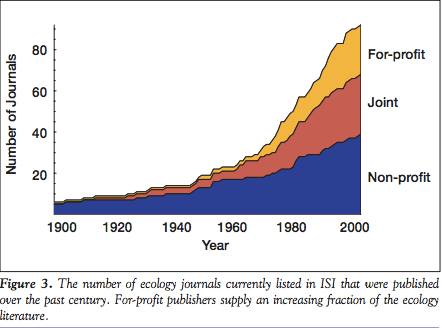

Academic journals developed in the 1660s as an efficient way for the new academies to spread their findings. The first started when Henry Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society, published the society’s articles at his own expense. At the time, the market for scientific articles was small and publishing a major expense. Scientists gave away the articles for free because the publisher provided a great value in spreading the findings at very little profit. When the journals market became more formal, almost all publishers were nonprofits, often associated with research institutions. Up until the mid 20th century, profits were low and private publishers rare.

Universities have since replaced academies as the dominant scientific institution. Due to the rising costs of research (think linear accelerators), governments replaced individual patrons as the biggest subsidizer of science, with researchers applying for grants from the government or foundations to fund research projects. And journals transitioned from a means to publish findings to take on the role of a marker of prestige. Scientists’ most important qualification today is their publication history.

Today many researchers work in the private sector, where the profit incentives of intellectual property incentivize scientific discovery.

But outside of research with immediate commercial applications, the system developed in the 1600s has remained a relative constant. As physicist turned science writer Michael Nielsen notes, this system facilitated “a scientific culture which to this day rewards the sharing of discoveries with jobs and prestige for the discoverer… It has changed surprisingly little in the last 300 years.”

The Monopolization of Science

In April 2012, the Harvard Library published a letter stating that their subscriptions to academic journals were “financially untenable.” Due to price increases as high as 145% over the past 6 years, the library said that it would soon be forced to cut back on subscriptions.

The Harvard Library singled out one group as primarily responsible for the problem: “This situation is exacerbated by efforts of certain publishers (called “providers”) to acquire, bundle, and increase the pricing on journals.”

The most famous of these providers is Elsevier. It is a behemoth. Every year it publishes 250,000 articles in 2,000 journals. Its 2012 revenues reached $2.7 billion. Its profits of over $1 billion account for 45% of the Reed Elsevier Group – its parent company which is the 495th largest company in the world in terms of market capitalization.

Companies like Elsevier developed in the 1960s and 1970s. They bought academic journals from the non-profits and academic societies that ran them, successfully betting that they could raise prices without losing customers. Today just three publishers, Elsevier, Springer and Wiley, account for roughly 42% of all articles published in the $19 billion plus academic publishing market for science, technology, engineering, and medical topics. University libraries account for 80% of their customers. Since every article is published in only one journal and researchers ideally want access to every article in their field, libraries bought subscriptions no matter the price. From 1984 to 2002, for example, the price of science journals increased nearly 600%. One estimate puts Elsevier’s prices at 642% higher than industry-wide averages.

These providers also bundle journals together. Critics argue that this forces libraries to buy less prestigious journals to gain access to indispensable offerings. There is no set cost for a bundle, instead providers like Elsevier structure plans in response to each institution’s past history of subscriptions.

The tactics of Elsevier and its ilk have made them an evil empire in the eyes of their critics – the science professors, library administrators, PhD students, independent researchers, science companies, and interested individuals who find their efforts to access information thwarted by Elsevier’s paywalls. They cite two main objections.

The first is that prices are increasing at a time when the Internet has made it cheaper and easier than ever before to share information.

The second is that universities are paying for research that they themselves produced. Universities fund research with grants and pay the salaries of the researchers behind every paper. Even peer review, which Elsevier cites as a major value it adds by checking the validity of papers and publishing only significant and valuable findings, is performed on a volunteer basis by professors whose salaries are paid by universities.

Elsevier actively responds to each challenge to its legitimacy, refuting point by point and speaking of “work[ing] in partnership with the research community to make real and sustainable contributions to science.” Deutsche Bank, in an investor analyst report, summarizes Elsevier’s arguments:

“In justifying the margins earned, the publishers point to the highly skilled nature of the staff they employ (to pre-vet submitted papers prior to the peer review process), the support they provide to the peer review panels, including modest stipends, the complex typesetting, printing and distribution activities, including Web publishing and hosting. REL [Reed Elsevier] employs around 7,000 people in its Science business as a whole. REL also argues that the high margins reflect economies of scale and the very high levels of efficiency with which they operate.”

How do their arguments stand up?

One means of analysis is to compare the value of for profit journals to non-profits. Within ecology, for example, the price per page of a for profit journal is nearly three times that of a non-profit. When comparing on the basis of the price per citation (an indicator of a paper’s quality and influence), non-profit papers do more than 5 times better.

Another is to look at their profit margins. Elsevier’s profit margins of 36% are well above the average of 4%-5% for the periodical publishing business. Its hard to imagine that no one could do the centuries old business of publishing papers at lower margins. The aforementioned Deutsche Bank report concludes similarly:

“We believe the [Elsevier] adds relatively little value to the publishing process. We are not attempting to dismiss what 7,000 people at [Elsevier] do for a living. We are simply observing that if the process really were as complex, costly and value-added as the publishers protest that it is, 40% margins wouldn’t be available.”

Libraries point to the high cost of journal subscriptions as a problem. It has been reported as far back as 1998 by The Economist. But now even the world’s wealthiest university cannot afford to purchase access to new scientific knowledge – even though universities are responsible for funding and performing that research.

No One to Blame but Ourselves

For critics of private publisher’s monopolization of the journal industry, there is a simple solution: open access journals. Like traditional journals, they accept submissions, manage a peer review process, and publish. But they charge no subscription fees – they make all their articles available free online. To cover costs, they instead charge researchers publication fees around $2,000. (Reviewers not on payroll decide which papers to accept to spare journals the temptation of accepting every paper and raking in the dough.) Unlike traditional journals, which claim exclusive copyright to the paper for publishing it, open access (OA) journals are free of almost all copyright restrictions.

If universities source the funding for research, and its researchers perform both the research and peer review, why don’t they all switch to OA journals? There have been some notable successes in the form of the Public Library of Science’s well-regarded open access journals. However, current scientific culture makes it hard to switch.

A history of publication in prestigious journals is a prerequisite to every step on the career ladder of a scientist. Every paper submitted to a new, unproven OA journal is one that could have been published in heavyweights like Science or Nature. And even if a tenured or idealistic professor is willing to sacrifice in the name of science, what about their PhD students and co-authors for whom publication in a prestigious journal could mean everything?

One game changer would be governments mandating that publicly financed research be made publicly available. Every year the United States government provides over $60 billion in public grants for scientific research. In 2008, Congress mandated (over furious opposition from private publishers) that all research funded through the National Institute of Health, which accounts for 50% of government funding of science, be made publicly available within a year. Extending this requirement to all other research financed by the government would go a long way for OA publishing. This is true of similar efforts by the British and Canadian governments, which are in the midst of such steps.

The Costs of Closed Publishing: The Reinhart-Rogoff Paper

The controversy over the 2010 paper “Growth In A Time of Debt,” published by Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff in the American Economic Review, illustrates some of the problems with the journal system.

The paper used a dataset of countries’ rate of GDP growth and debt levels to suggest that countries with public debts over 90% of their GDP grow significantly slower than countries with more modest levels of debt.

To the media that covered their findings and the politicians and technocrats that cited it, the message was clear: debt is bad and austerity (reducing government spending) is good. Although they discussed their findings with more nuance, Reinhart and Rogoff obliged Washington by discussing how their findings supported the case for deficit reduction.

But this past April, a group of researchers from UMass Amherst revealed that the Reinhart-Rogoff paper was wrong. Like many economists, the researchers had been trying unsuccessfully to replicate Reinhart and Rogoff’s findings. Only when the Harvard economists sent them their original dataset and Excel spreadsheet did the UMass team discover why no one could replicate the findings: the economists had made an Excel error. They forgot to include 5 cells of data. Noting this mistake, and the exclusion of a number of years of high debt growth in several countries and a weighting system that they found questionable, the UMass team declared that the effect Reinhart and Rogoff reported disappeared. Instead of contracting 0.1%, the average growth rate of countries with debt over 90% of GDP was a respectable 2.2%.

The mistake was caught, but for 2 years the false finding influenced policy-makers and informed the work of other economists.

Bad Incentives

Moving to open access journals would expand access to scientific knowledge, but if it preserves the idolization of the research paper, then the work of science reformers is incomplete.

They argue that the current journal system slows down the publication of science research. Peer review rarely takes less than a month, and journals often ask for papers to be rewritten or new analysis undertaken, which stretches out publication for half a year or more. While quality control is necessary, thanks to the Internet, articles don’t need to be in a final form before they appear. Michael Eisen, co-founder of the Public Library of Science, also notes that, in his experience, “the most important technical flaws are uncovered after papers are published.”

People celebrate the discovery of new drugs, theories, and social phenomena. But if we conceptualize science as crossing out a list of possible hypotheses to improve our odds of hitting on the correct one, then experiments that fail are just as important to publish as successful ones.

But journals could not remain prestigious if they published litanies of failed experiments. As a result, the scientific community lacks an efficient way to learn about disproven hypotheses. Worse, it encourages researchers to cherry pick their data and express full confidence in a conclusion that the data and their gut may not fully support. Until science moves beyond the journal system, we may never know how many false positives are produced by this type of fraud-lite.

A Scientific Process for the 21st Century

Although scientists are the cutting edge, there are many instances of missed opportunities to make the process of science more efficient through technology.

As part of our look at academic journals and the scientific process, we talked with Banyan, a startup whose core mission is open science. A surprisingly illuminating moment was when we learned how much low hanging fruit is out there. “We want to go after peer review,” CEO Toni Gemayel told us. “Lots of people still print their papers and [physically] give them to professors for review or put them in Word documents that have no software compatibility.”

Banyan recently launched a public beta version of their product – tools that allow researchers to share, collaborate on, and publish research. “The basis of the company,” Toni explained, “is that scientists will go open source if given simple, beneficial tools.”

Physicist turned open science advocate Michael Nielsen is an eloquent voice on what new tools facilitating an open culture of sharing and collaboration in science could look like.

One existing tool that he advocates expanding upon is arXiv, which allows physicists to share “preprints” of their papers before they are published. This facilitates feedback on ongoing work and disseminates findings faster. Another practice he advocates – publishing all data and source code used in research projects along with their papers – has long been called for by scientists and could be accomplished within the journal framework.

He also imagines new tools that don’t yet exist. A system of wikis, for example, that allow scientists to maintain perfectly up to date “super-textbooks” on their field for reference by their fellow researchers. Or an efficient system for scientists to benefit from the expertise of scientists in other fields when their research “gives rise to problems in areas” in which they are not experts. (Even Einstein needed help from mathematicians working on new forms of geometry to build his General Theory of Relativity.) For a full account of his proposals, see his excellent essay, “The Future of Science.”

But none of these ideas are likely to take off on a mass scale until scientists have clear incentives to contribute to them. Since publication history is all too often the sole metric by which a scientist’s work is judged, a scientist who primarily assembles data sets for others to use or maintains a public wiki of meta-knowledge of the field will not progress in his or her career.

Addressing this issue, Toni references the open spirit amongst coders working on open-source software. “There’s no reward system right now for open science. Scientists’ careers don’t benefit from it. But in software, everyone wants to see your GitHub account.”

Talented coders who could make good money freelancing often pour hours of unpaid work into open-source software, which is free to use and adapt for any purpose. On one hand, many people do so to work on interesting problems and as part of an ethos of contributing to its development. Thousands of companies and services (including Priceonomics’s price guides) would simply not exist without the development of open-source software.

But coders also benefit personally from open-source work because the rest of the field recognizes its value. Employers look at their open-source work via their GitHub accounts (by publicly showing their software work, it can effectively function as a resume), and people generally respect the contributions people make via open-source projects and sharing valuable tips in blog posts and comments. It’s the exact type of open pursuit that you would expect in science. But we see it more in Silicon Valley because it is valued and benefits people’s careers.

Disrupting Science

“The process of scientific discovery – how we do science – will change more over the next 20 years than in the past 300 years.” ~ Michael Nielsen

The current model of publicly funding research and publishing it in academic journals was developed during the days of Isaac Newton in response to 17th century problems.

Beginning in the 1960s, private companies began to buy up and unduly profit off the copyrights they enjoyed as the publishers of new scientific knowledge. This has caused a panic among cash-strapped university libraries. But the bigger problem may be that scientists have not fully utilized the Internet to share, collaborate, and invent new ways of doing science.

The impact of this failure is “impossible to measure or put an upper bound on,” Toni told us. “We don’t know what could have been created or solved if knowledge wasn’t paywalled. What if Tim Berners-Lee had put the world wide web behind a paywall. Or patented it?”

Advocates of open science present a strong case that the idolization of publishing articles in journals has resulted in too much secrecy, too many false positives, and a slowdown in the rate at which scientific discoveries are made. Only by changing the culture and incentives among scientists can a system of openness and collaboration be fostered.

The Internet was created to help scientists share their research. It seems overdue that scientists take full advantage of its original purpose.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.