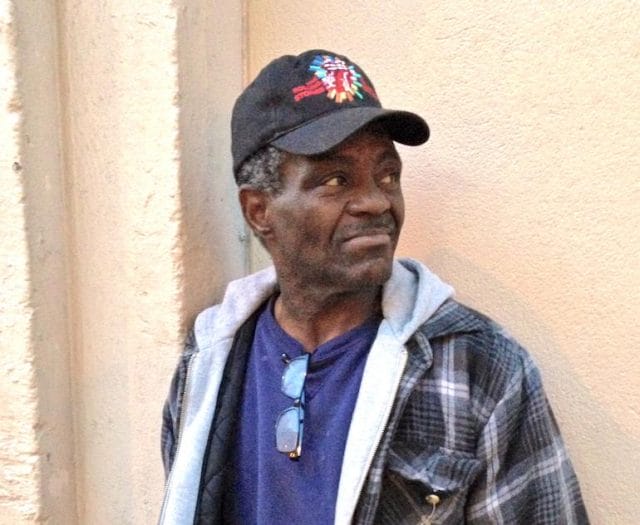

Nathaniel only trusts two people: “Jesus, and a MUNI driver named Curtis.” In the heart of the city, off homeless-dense Market Street, he bumbles along the brick wall of an alleyway, watching his shadow shuffle one step ahead. He has trouble making eye contact. As if bearing some great weight, he hunches, hiding his face beneath the brim of a colorful Rolling Stones cap. He’s 57 with poor eyesight. A new pair of reading glasses — his only Christmas gift this year —dangles from the loose neck of his t-shirt, and he occasionally pauses to make sure they’re still safe.

One of 7,000-10,000 homeless residents of San Francisco, Nathaniel, or “Nate the Great,” as his mother once called him, is particularly worn down tonight, and at the end of his wits.

“I’m tired, my feet hurt, my shoes got holes in them,” he says without an iota of self-pity. “Thankfully, the holidays are over. It ain’t bad you know, but another year, and the same old thing. You haven’t moved along.”

He’s been roaming Market Street for 15 years. Like most homeless who are not sheltered in the city (about 50%), Nate subsists on what he makes panhandling throughout the day — usually $10-15 over the course of 15 hours, from 9 am to 12 am. There’s the occasional rare day where he’ll pull in $50. And then there was that one time he woke up with a coffee tin full of $300 in quarters. But he hasn’t seen a day like that for a long time. Today, he “retires early” at 5 pm with four dollars and nineteen cents in his pocket.

Nate the Great grew up in Oakland and spent his early days selling Coca-Cola bottles in front of his neighborhood store. He was a good student, worked hard, and contributed what little he made to his mother’s rent check. With two brothers and two sisters, Nate’s resources were spread thin, so he never turned down an opportunity to make a few dollars. His mother’s salary often didn’t cover her expenses, and the family routinely toggled between the street and cheap motels. But Nate insists “the good lord had it all under control.”

In October, 1966, when Nate was 10 years old, he recalls meeting Bobby Seale, a founding member of Oakland’s Black Panthers. “I was washing up at a diner bathroom, and he came out a stall, looked in the mirror at me, and smiled. Didn’t know who he was, but when I left, my ma told me to remember that man, he was the savior of the hood. After that, he was the man I wanted to be.”

But a revolutionary isn’t all Nate wanted to be. He was a dreamer and would imagine fantasy worlds. “I’d see myself flying,” he says, peering up at the smokestacks and cables above him. His memories are vivid, and they dance in his eyes. “Just floating on through Oakland, up and over the port, out into the sea, you know…”

But behind these dreams was the bleak landscape of his reality. Juggling odd jobs and an unstable family life, he struggled through high school. Nonetheless, Nate earned his GED, joined the Army as an infantryman and was deployed to Korea, where he spent the next seven years. Several times, he says, he was involved in crossfire between insurgents and the military, and he experienced the death of a close friend.

In 1983, he returned to Oakland, secured a job as a furniture-maker, and rented himself a tiny apartment in Sixty-Ninth Village, a neighborhood notorious for crime and gang activity. He drilled windsor chair mortises for minimum wage, took great pride in his work, and shied away from most interaction on the streets.

“I always kept to myself,” he says, shuffling his feet and occasionally glancing up at a truck rumbling by. “Still do. I don’t play the game out here.”

The game he’s referring to is what most homeless people on the streets of San Francisco do to survive: network, make connections, barter, band together. As Nate says, “It’s who you know to get what you want.”

He talks of the “bootleg recycling community” — a group of entrepreneurs in Hunter’s Point who buy bottles and cans from homeless collectors for 50 cents per pound and flip them for 90 cents per pound at a recycling center. This black market was created when city officials closed down the Safeway recycling centers that the homeless community relied on to make a few bucks, typically $2-3 for each large bag full of recyclables.

Another part of the “game” is getting to know the local beat police officers who patrol the neighborhood. Instead of befriendingofficers, Nate has avoided confrontation by staying “in places where the sun don’t shine”: the obscure alleyways and crevasses of the city. For 15 years, he has taken pride in being an invisible man. Sick of bustling city center life, he once tried to “rough it” in Golden Gate Park, but he was “scared off by all the wild animals.” At 6’1’’, 240 pounds, Nate still cowers at the thought of “coon encounters.”

He says that over the years, police have “corralled” the homeless into the Tenderloin, and that when an officer sees him out and about on Market Street, he is ordered to disappear from the sight of tourists and local residents. He obliges.

Nate’s life changed forever in 1990.

According to Nate, a man broke into his apartment in the middle of the night, held him at gunpoint, and demanded money and valuables. Instead, Nate tackled the intruder, wrestled his gun away, and shot the fleeing man five times. In a disoriented, panic-induced frenzy, he fled his own apartment and was apprehended by police. A brief trial found Nate guilty of involuntary manslaughter; a psychiatric evaluation determined that he was legally insane, and he was committed to a psychiatric ward in San Francisco.

Released with a criminal record and battling PTSD, Nate struggled to find his place in San Francisco’s social landscape. He worked for a cab company for a few months, but it went out of business and laid him off. He tried to find work assembling furniture, but was only offered manual labor jobs, lifting heavy couches and armchairs. He took the opportunity, but was paid under-the-table at far below minimum wage. The work was grueling, and the wages weren’t enough to support himself. He applied for, and began to receive, welfare checks — $380 per month — but they were soon cut off when they found out he had a job.

Between 1992 and 1998, Nate worked during the day, earning $40 for eight hours’ work, and slept in shelters at night. After witnessing a stabbing in a shelter in late 1997, he grew increasingly disillusioned with quality of care and safety standards, and took to the streets to fend for himself. Within the week, he was out of work and began to panhandle.

At first, the $15 or so a day was spent on “donuts, coffee, and cookies.” Then, after a lifetime of resisting drugs, he tried crack for the first time, at age 41. For the first time since he was a child, he felt like he was flying, ascending above the madness and filth of daily life. He lost himself in the illusion of escape, began trying less, and gave up hope. Instead of fighting to get off the streets, he accepted his fate and became “one of the zombies on Van Ness.” A dark period ensued, and he relinquished himself entirely to the drug for two years.

In 2000, he began to slowly pick himself up. He swept the streets in front of liquor stores for $5 a day — less than $1 per hour, for a job “street cleaners are paid $25 an hour” to do. Once in a while, he secured work painting an old building or “cleaning raggedy hotels up.” These days, he’ll take any job, he says, except dealing drugs — a gig he’s offered nearly every week by local gangs. He has some friends who he says have escaped the streets, but he estimates 95% of them now work at shelters and are unsympathetic to those who haven’t been able to break out of the cycle. “The ones who get the good jobs,” he says, “turn against the homeless community. They work in shelters, come back and call you a bum. “

New laws in the city have made it illegal for him to sit on a sidewalk between 7 am and 11 pm, so he wanders aimlessly for hours. When he needs to use the restroom, he has to buy a coffee or pie at McDonalds; sometimes, they refuse him service because he “smells funky.” He owns nothing and has no desire to accumulate belongings, which he thinks will weigh him down. Despite this, other homeless people attempt to steal his shoes every night. If they did, it probably wouldn’t bother him much. He found his current pair on a stoop along Pine Street a few nights ago.

“Once you in the cycle, it’s vicious to escape. When the people who run the city mark you as homeless, they’re 80-90% done with you.” Nate kicks a can as he stumbles along, and raises his eyebrows while reflecting. “What really messed me up was when I got that conviction. I was never quite the same. I ain’t crazy, man.”

The sun has gone down, and the city streets we walk through are dark, unlit, and especially cold. Nate’s sharp breaths have become visible, fleeting clouds. He stops suddenly and turns, as if to greet someone who has surprised him. “Let me tell you something. One day, you could be the same way. I hope you ain’t, but you can be.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.