Every morning, a dozen men and women line the sidewalk outside the San Francisco Community Recyclers center. Each has a shopping cart or trash bags filled with bottles and cans.

Behind the recycling center, homeless people sprawl out in an area where social services regularly distribute food. Commuters cruise past on the neighboring bike path and turn onto Market Street toward downtown. Beyond the cyclists, a Muni car rumbles into the subway and construction workers lift glass panes onto an apartment complex. “Modern Luxury. 115 New Residences,” the sign reads. “Now selling.”

The men and women are waiting for the center to open, at which point the staff will count or weigh their bottles and cans and hand them a check for their recyclables’ redemption value – the five or ten cent deposit added to the cost of beverages like soda, beer, and juice. Depending on the size of the haul, the checks could be worth from $2.50 to $50.

Everyone in line relies on these checks. The homeless earn the equivalent of up to minimum wage by picking up discarded cans. Seniors and the unemployed do the same to supplement their social security or welfare benefits. Low income families return their own empty beer bottles and soda cans for several hundred dollars of crucial income per year. Employees of modest cafes and restaurants redeem their establishments’ empties.

It’s a neat system that rewards recycling and litter reduction while serving as a safety net and mini jobs program for San Francisco’s neediest, and community recycling centers underpin the system. But Safeway, the supermarket that hosts the Market Street recycling center in its parking lot, has served the center with an eviction notice. As of October 4, the center remains open only due to legal action challenging the eviction.

If the challenge is unsuccessful, it will be the fifth center in San Francisco to close this year – a policy supported by city hall. The Market Street center is the last one accessible to residents of the city center. Its customers don’t know what to do when it closes.

Despite its reputation as one of the most liberal, environmentally conscious cities in the country, San Francisco has systematically shut down recycling centers. We sought to find out why.

The Lives of Can Collectors

“You grab a shopping cart and hit the bars when they put out their bins and you get 30 bucks. It’s legal money, you know?”

Francis lived with his girlfriend in Milwaukee before laying a sleeping bag out on Market Street and collecting cans. He was a starving artist; she worked as a paralegal. Between a drug habit and her losing her job, the two lost all their money and their apartment. Francis came to San Francisco in the hopes that his glassblowing hobby would allow him to sell glass pipes in a city famous for marijuana culture.

Chris is a victim of the recession who supplements his General Assistance (welfare) check with can redemptions. “I used to work for myself,” he told us. But his window washing business lost too many customers, and a blood clot in his leg aggravates both his can collecting and efforts to find employment.

Peter is a retired immigrant living in Chinatown who collects $20 of cans a month to pay his medical bills. Kevin King became homeless after losing his bartender and waiter jobs. He has an upcoming appointment with a social worker. “I’m ready to get help,” he told us. “To find a job.”

Many customers of the recycling centers come once a week to redeem bottles and cans they themselves bought. But for men like Francis, Chris, and Kevin, the center is a base of operations where they return once, twice, or even three times a day. It is the headquarters of a full or part time job that pays poorly and is grueling work, but is open to anyone, anytime.

Among those approaching it like a full time job, recyclers at the Community Recycling Center earn $30-$50 per day. That equates to 3 to 5 trash bags filled with around 700 bottles and cans. The man in the picture below estimated that he had $23 worth.

But wandering in search of cans from 9am to 5pm won’t earn anywhere close to minimum wage. With so many people scouring the same streets and public trash cans, bottles are scarce most of the day. So, collecting cans is all about the night shift, when fewer collectors compete for bottles and drunken revelers discard empties on the street. Of Francis’s daily income of $40, thirty comes from several hours of nocturnal scavenging. Each scavenging trip during the day only earns him around $5.

Collecting in neighborhoods far away from the nearest recycling centers or in hilly neighborhoods is another option, but less attractive. Competition is reduced, but it’s the equivalent of taking a job with a better salary and longer commute – a commute that involves lugging hundreds of cans up and down hilly San Francisco. “If the cart gets away from you…” Francis warned us.

Using a shopping cart also represents a tradeoff. It works well but attracts suspicion, especially from cops who confiscate recyclables transported in a stolen shopping cart.

Even at night, however, competition for cans is high. To maximize nightly haul, can collectors compete for the valuable contents of curbside recycling bins left out by residents, eateries, and bars for collection by the trash service.

This is illegal. Once placed on the curb, all recycling, trash, and compost within the bins belongs to Recology, the private company responsible for San Francisco’s trash and recycling collection. “When someone steals bottles and cans from families’ blue [recycling] bins, they take money from that families’ pocket,” Robert Reed of Recology told us. “Material in the blue bins is sorted, baled, and sold, and that revenue comes back to help pay for the recycling program.”

Many recyclers decide not to scavenge from curbside bins after residents complain. Many others still do. The police, however, do not consider the theft of cans a priority.

A bigger concern for recyclers is organized competition.

Large buildings and businesses keep their recyclables in locked facilities and contract industrial size trucks to collect it. But small establishments use curbside collection, and bars that do may leave out hundreds of dollars worth of empties over the course of a night. Knowing when neighborhoods put out their curbside recycling is key. “I’ve definitely got the schedule in the back of my mind,” one recycler told us.

That attracts larger operations – fleets of pickup trucks that fill their beds with stolen recycling. Local police and newspapers call them mosquito fleets. Francis compared competition over blue bins to a race: “You have to be fast because the Mexicans show up in trucks to grab it all,” he told us. Can collectors describe the drivers of these pickup trucks as aggressive and territorial. “The trucks?” Kevin King replied to our questioning. “They’re pretty much [jerks]. They’re the ones who say it’s ‘their turf.’ They can be dangerous.”

Nevertheless, many can collectors work with the mosquito fleets. Since recycling centers close at night, recyclers face a bottleneck once they fill their bags and carts. As a result, many sell their bottles and cans to truck drivers for 20 or 30 cents on the dollar so they can keep collecting cans during prime hours. But the truck drivers are stingy, so the profit-maximizing strategy is often to redeem the cans oneself.

Despite the bottleneck, which favors truck drivers over individuals, can collecting is more lucrative than we imagined. Making $50 from recycling every day translates to over $18,000 a year. That’s more than a Federal minimum wage earner working thirty hour weeks.

But collecting cans is a tough way to make a living. Traipsing around San Francisco all night is very different from scavenging during the day. Francis recommends a flashlight to avoid broken glass. A few recyclers sport gloves to deal with unexpected nastiness. Recyclers also contend with rats and raccoons.

“The rats are audacious, man. They don’t run. I open up bins and they look up at me like ‘What?’”

The importance of the night to can collection is probably why so few women collect cans. Each night, Francis sees “a lot of criminal activity” from identity thieves picking through trash to burglars shining flashlights into cars as they search for valuables worth a break-in.

The daily average income from redeeming cans also misleads about how much recyclers make over time.

The financial rewards of collecting cans is proportional to the effort put in. “You can make as much as you want if you put in the legwork,” Francis told us.

But keeping up the pace is hard, physical work. Francis once found a pedometer and measured that he walked the equivalent of the perimeter of San Francisco (28 miles) in a day. “The cart gets so heavy,” he told us. He has taken weeks off to rest his cracked and swollen feet, and can collectors don’t get sick days. “The best part of my day is going to sleep,” he told us.

Homeless can collectors often rely on dumpster diving. It’s bleak but rewarding. As we pass Starbucks, Francis tells us that “It’s awesome” when Starbucks trashes leftover pastries. Digging through residents’ trash bins for recyclables is “like a treasure hunt.” Francis has found nice bags, iPods, discarded weed, and a brand new leather jacket. Some he keeps; some he sells. But the valuable stuff comes along too rarely to depend upon. Francis also appreciates charitable residents who – aware of dumpster divers – leave out food, socks, and other donations.

Recyclers also fail to reach their full earnings potential because there is little reason to. The stigma of homelessness keeps most from getting a job, apartment, or bank account. Those with apartments have similarly bleak prospects. The work is unpleasant, so why overachieve?

It’s a sad fact, but not without an upside. Francis appeared dead on his feet from constantly searching for recyclables. Kevin, in contrast, works the most lucrative night hours, then spends the day enjoying a beer in the park and emailing his daughter from a library computer. “I don’t need no $50 bag,” he says, pointing to the recyclers carrying hundreds of cans with the equanimity of a self-help guru. He takes a bite of pasta. “This was $1.50,” he announces. “And it’s delicious!”

Valuing Recycling

On sunny days, San Franciscans fill Dolores Park to picnic, drink, and throw frisbees. When the sun sets and the crowds leave, forgotten bags and discarded packaging material litter the ground. Despite the many PBRs and glasses of wine consumed, however, there is no sign of a can or bottle. All day, low income individuals have scoured the park for empties. Whenever a picnicking hipster finishes a beer, someone immediately appears to take it from him. Everyone in the park is provided with reverse bottle service.

Were it not for California’s Bottle Bill, this would not be the case.

The first community recycling operations appeared in San Francisco in the 1970s. They followed two decades of increasing environmentalism efforts including the first celebration of Earth Day, the Clean Air Act, and the founding of the Environmental Protection Agency. By the early 1980s, all the precedents of modern recycling systems existed. Scavenger associations dating back to Italian immigrants making a living by recycling materials gave way to formal, licensed operators and the first curbside collection bins. (New, unlicensed scavengers were partly responsible for the failure of curbside bins at the time.) Community recyclers ran small buyback programs.

But the expense of recycling limited its growth. As Ed Dunn, Executive Director of the San Francisco Community Recycling Centers, explained, the scrap value of plastic and glass was simply too low to support anything but an industrial recycling center – the type of place far from residential areas that recycled material by the truck load. Running smaller recycling centers in accessible parts of town was prohibitively expensive. As a result, households trashed their bottles. Streets and public trash cans filled with empties.

In 1986-1987, California followed the example of other states and passed the Beverage Container Recycling and Litter Reduction Act, also known as The Bottle Bill. It taxes companies like Coca Cola and Anheuser Busch five to ten cents per beverage sold – a cost usually passed onto customers in the form of higher prices. Consumers reclaim those extra 5 or 10 cents by dropping off their empties at a recycling center. At the same time, the funds paid to the state by beverage companies that go unclaimed by the public subsidize a statewide system of nonprofit recycling centers like the one on Market Street, which give people an accessible means of recycling and redeeming bottles and cans for their “California Redemption Value.”

The bill also created a statewide corps of recycling litter-fighters like Francis. They are not an accidental outgrowth of the legislation. Placing a monetary value on recyclables allows those motivated by the cans’ deposit value to compensate for the better off who are not. Can collectors are also at times formally integrated into the recycling ecosystem – Dunn notes that San Francisco’s public garbage bins have small, open tops for bottles and cans to encourage individuals to collect and recycle them.

With only a marginal impact on beverage companies and consumers, the Bottle Bill has made progress on its goals. The state recycling rate for eligible containers increased from 52% in 1988 to 82% in 2011. Advocates of the bottle bill also cite its success in reducing litter. According to government funded before-and-after studies, “states showed reductions in beverage container litter ranging from 69% to 84%, and reductions in total litter ranging from 30% to 65%.”

What Fewer Recycling Centers Means for San Francisco

If the community recycling center on Market Street loses its legal battle with Safeway, it will be San Francisco’s fifth center to close its doors this year. The choice of these 5 (in purple, below) is not random. They were located in central, residential areas where individuals – especially those without cars – could conveniently access them.

Many low income families will lose a crucial source of income as a result. One study undertaken in Santa Barbara found that families earning under $10,000 a year made, on average, $340 redeeming scavenged empties. “I don’t know where to go when this closes,” a mother of four redeeming her families’ bottles and cans told us. “I used to go to the centers near Geary and Broadway, but they closed. The only places left are so far away it’s not even worth the trip.”

The loss of the center is the equivalent of a pink slip to the many individuals collecting cans full time. The remaining centers are too far from the areas where people can collect cans, as well as the stores they rely on. “I’ll probably have to start spangeing by the highway,” Francis told us, referring to begging or asking, “Spare change?”

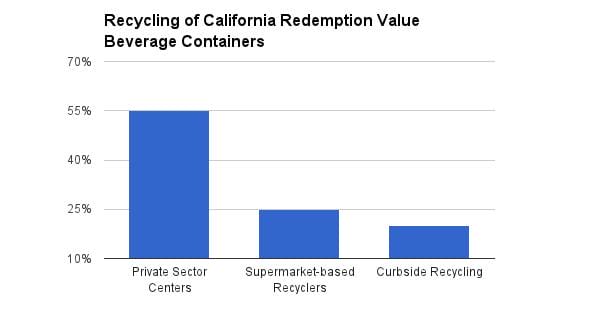

The center’s closure will also impair San Francisco’s recycling goals as community recycling centers account for as much as one third of recycled bottles and cans.

Data Source: Californians Against Waste

The theft of recyclables from blue bins may skew this data. But the nonprofit Californians Against Waste noted studies suggesting that people do redeem cans at high rates. For example, a survey of Sacramento County residents found that 93% redeemed or donated aluminum containers rather than put them out for collection.

California’s cities and towns provide one center offering recycling buybacks for every 16,000 residents. San Francisco, with one center for every 38,000 residents, is the most underserved area in the state. And the reason seems to be that the city now values aesthetics over its recycling program.

Why Recycling is no Longer Welcome in San Francisco

Eric Dunn of Community Recyclers does not hesitate when we ask him why the recycling centers have closed: “Getting rid of street people by getting rid of recycling centers is the bottom line. It’s basically class warfare concerns.”

His staff and customers share a sense of victimization. “The yuppies don’t want us around and to hear all the cans while they get their breakfast,” a homeless man tells us. “It’s war on the poor.”

Safeway and local politicians provide a number of reasons justifying the eviction of community recycling centers. The motivation to tidy up neighborhoods for residents who don’t use the centers seems to be the primary reason.

A new highrise sits across the street from the recycling center.

Safeway did not respond to our interview requests, but a spokesman made the following statement on the eviction of the Market Street recycling center:

The widespread availability of curbside recycling makes such facilities obsolete, and the facility has a negative impact on customers and neighbors.

These twin explanations of curbside recycling rendering the centers unnecessary and the centers’ negative impact have been echoed by local politicians such as District Supervisor Scott Wiener, who told the press, “I’ve been asking Safeway to consider alternatives to the recycling center on Market Street since I took office.” City hall cites the same motivation, as when the office of former mayor Gavin Newsom pursued the eviction of a recycling center in Golden Gate park, which was situated on city property.

But curbside recycling is sufficient only for those rich enough not to care about the redemption value of cans. As Joe Rice of the Market Street center put it, “Curbside doesn’t put money in grandmothers’ pockets.” And as many beverages are consumed outside the home, recycling centers are still crucial to San Francisco’s stated goal of zero waste by 2020.

The recycling centers do enable theft from blue recycling bins. But we see no evidence that the city has weighed this downside against the benefits of the recycling centers. The financial footprint is certainly small. Douglas Legg, who oversees Recology’s collection rates as Manager of Finance, Budget and Performance in the Department of Public Works, ballparks the cost of bottles and cans theft at around $1.8 million annually. The department believes that theft increases the collection rates paid by residents and businesses to have their trash and recycling picked up every week by 1%-2%. Even critics of the community recycling centers acknowledge that it’s a “quality of life issue,” rather than financial problem. Recology receives hundreds of complaints from San Franciscans about noise, litter, and trespassing.

Is that a bearable inconvenience for the benefits rendered by the center? That debate does not seem to have taken place. Evicting the centers will do nothing about homeless people rooting around in people’s recycling bins. “After the center’s gone, people will just sell to the trucks,” Francis told us. The mosquito fleets have no use for neighborhood recycling centers, which operate a scale the size of a bedroom scale. Instead, they drive their stolen recyclables to private centers that have industrial size truck scales. Removing the centers will only send thieves flocking toward the black market.

The real logic of the evictions – to make neighborhoods nicer for those who don’t need the centers – is best expressed by more blunt commentators. A columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle cheerleads the eviction of the Market Street center:

It seems likely that this will reduce the number of unkempt scavengers who have taken over the parking lots.

Commenting on a story about the eviction, a resident writes:

Overjoyed with the closing of this smelly place. We live on Duboce and my daughter is buying one of the new condos over there. Frankly, I was worried the stink and the noise from that facility would be disruptive at her new home. Plus, I did not want us to pay all that money and have a view of the disgusting mess of the recycling center area.

Accessible recycling centers are also not just one interest jockeying among many. They are a legal right under the Bottle Bill, which mandates that a redemption center must be available within a half mile “zone of convenience” from large supermarkets that sell beverages in bottles and cans. In the below map, each black circle represents a supermarket with a center; each red circle a zone without one.

Dotted red lines have won an exemption from the law, but all others violate the law. If customers ask, supermarkets must either redeem cans themselves or pay a fine of $100 per day – as must all stores and cafes in the area. This is the basis of the Community Recyclers’ legal challenge to their eviction. Safeway has promised to replace the recycling centers with automated vending machines that redeem recyclables, but it seems an empty promise. As soon as there are enough vending machines, they will attract the same “undesirable” clientele. One of the five evicted recycling centers consisted of the vaunted vending machines. Ed Dunn claims it closed for this exact reason.

One of the most frustrating aspects of the recycling centers’ eviction for its supporters is how they seem to get blamed for all the ills of the neighborhood. Residents complain about can collectors dumping their garbage and recycling on the ground. But so too do other can collectors who call them “shredders” and worry that their disrespect impugns all scavengers. Residents see the drug addicts hanging out near the center and assume a connection, even though relatively few are customers of the recycling center. Those eager to see the neighborhood cleansed of its unsightly recycling center also presuppose that the only customers are homeless, ignoring other low income customers. Politicians decry the mosquito fleets in statements about the recycling centers without acknowledging that the centers too are harmed by the trucks.

“The residents that criticize us sometimes behave poorly,” Joe Rice told us as he took us around the recycling center. “They leave their plastic bags of dog poop by our gate, and in one case even smeared the poop in our lock.” Rice’s logic seems to suggest that if he were to judge critics of the center the same way they judge the center’s customers, he would assume that all yuppies let their dogs poop on the sidewalk or use excrement to damage storefronts. People readily advocate for the closure of the recycling center due to the actions of a minority, but no one suggests banning the construction of fancy highrises because a few dog-loving yuppies leave bags of shit on the sidewalk.

Conclusion

San Francisco’s recycling ecosystem is a success in many ways. Thoughtful legislation that empowers individuals and organizations to move the needle on recycling has made San Francisco and California a leader in environmental issues. The people at the trash and recycling collection service company Recology are passionate about recycling and provide good value programs to the city. Community recycling centers like the one on Market Street complement industrial recycling centers on the outskirts of San Francisco by making redeeming cans accessible to residents.

The Market Street recycling center is still open, but it’s unlikely that it will stay that way for long. Without much thought to the pros and cons of the community recycling system, the city has undermined a key part of the recycling ecosystem by shutting down the centers in the center of San Francisco that are most accessible to residents of the city center.

As a result, the staff of those centers will lose their jobs, families struggling to scrape by during hard economic times will lose several hundred dollars of crucial yearly income, and homeless and unemployed individuals will lose the means to earn enough money to buy food or pay their rent in a way that gave them pride for helping perform a public service.

With accessible recycling centers, the Bottle Bill incentivizes recycling, reduces litter, and serves as a safety net for low income families. Without the centers, it’s just a tax that disproportionately hurts the poor. In order to beautify neighborhoods and please high-income San Franciscans, the city has chosen the latter option.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.