Source: Chuck Grimmett, Flickr

Over the past few years, Uruguay has become something of a media darling.

The country’s leader, José Mujica, is a walking news generator: he lives in a dilapidated farmhouse, drives a 1987 VW Beetle, and wears sandals to important ceremonies. Last April, he guided the passage of legislation that legalized same-sex marriage; before this, he encouraged lawmakers to make it easier for immigrants to obtain the same rights as residents. All the while, he has continued to boost Uruguay’s agriculture trade — the country is now a world leader in “cattle per capita,” and cows outnumber people four to one.

But perhaps most impressive was Mujica’s navigation through a bevy of legislators and critics to make Uruguay the world’s first authorized marijuana distributor. On December 10, 2013, Uruguay legalized the growth, sale, and consumption of cannabis, creating a model that will be a case study for nations debating the drug’s liberalization. For these efforts, The Economist named Uruguay its first-ever “country of the year.”

So, how will this legislation affect Uruguay’s loyal pot enthusiasts? More importantly, will Uruguay actually be able to undercut illegal drug traffickers? If so, how will the country’s new laws redefine the global drugs debate?

Uruguay’s Current Weed Market

On an international level, Uruguay has given off the impression of conservatism. In 1961, the country signed the “Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs,” an International Narcotics Control Board treaty that required parties to “limit [marijuana] use to medical and scientific purposes, due to its dependence-producing potential.” Again, in 1988, Uruguay ratified a United Nations treaty that criminalized the possession of weed.

But all the while, Uruguay has been domestically liberal with its handling of drug use. Since the country’s first marijuana law was passed in 1974, the personal use and possession of marijuana has never been criminalized. The old laws also didn’t specify the amount of marijuana one could legally possess, allowing for a smoker to have an unlimited supply of the drug. Until recently though, possession was legal but cultivation and sale were not.

This openness has, in part, made marijuana Uruguay’s favorite drug: in 2006, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimated that 6% of Uruguay’s population (aged 12-65) — roughly 200,000 citizens — smoked pot. Compared to other pot-smoking countries, this is fairly average. In the United States, this number is 13.6%. Papa New Guinea tops the list at 29.5%.

While Uruguay’s citizens have enjoyed liberal use laws, most of the country’s$30 million marijuana market is supplied by Paraguay via illegal trafficking. “Ricki,” a 28 year old marijuana user living in Montevideo, told us the weed he buys is almost always of this variety. He adds,

“We’re still smoking the same old Paraguayan stuff. It tastes like glue, because they press it up real tight to get across the borders. Everyone buys in the street, or from a preferred dealer. The illegal weed business makes up 99% of what’s smoked here.”

What Does the New Bill Change?

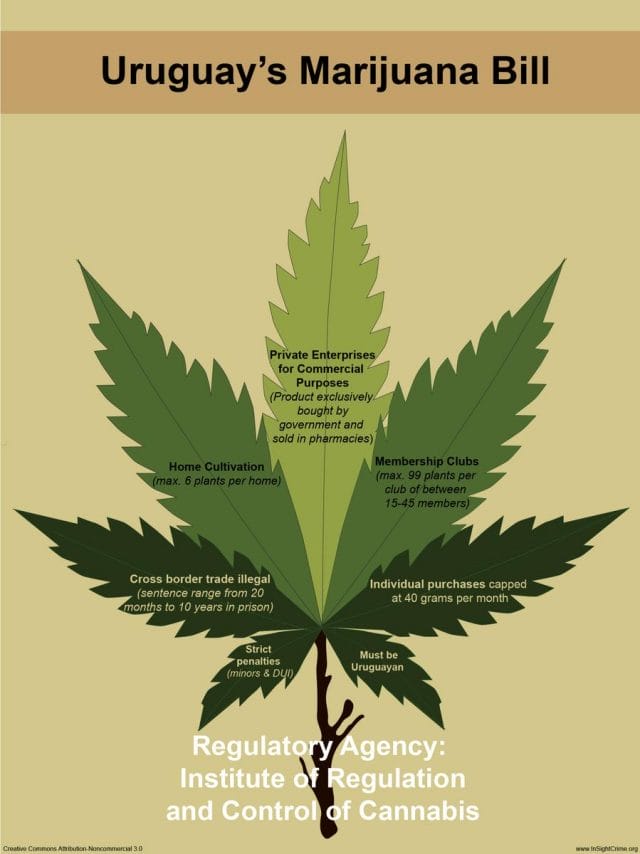

Source: InSight

José Mujica aims to rid his country of this foreign market reliance. His bill, which has been in the works for three years, seeks to turn Uruguay into a sole supplier in the hopes of replacing illegal dealers and drug traffickers. While Uruguay has some of the lowest crime rates in South America, Mujica’s approach is motivated by a strong desire to mitigate the social and criminal damages inflicted by cartels. There is also another distinct advantage in making the country the sole supplier, as opposed to opening dispensaries. “We can identify who is consuming,” says Mujica. “If we identify consumers, we can help them. If we criminalize them and keep them underground, we steer them towards drug dealers and wash our hands of responsibility.”

In 120 days, Uruguayan residents over the age of 18 will be able to purchase up to 40 grams (1.4 ounces) of marijuana each month. When someone buys federal weed, he will be registered in a government database (similar to California’s Medical Marijuana Program) and his purchases will be monitored.

The law will also allow for the personal growth of up to six marijuana plants per year (or up to 17 ounces); groups of smokers can band together and collectively grow up to 99 plants per year. By April, Uruguay plans to roll out an amalgam of licensed pharmacies at which residents can buy state-grown marijuana over the counter. For the first time anywhere, a country will control the cannabis market “from growing the plants to buying and selling its leaves.” Uruguay will create a new government office, the Institute of Regulation and Control of Cannabis (IRCCA), which will oversee implementation.

Julio Calzada, the country’s drug chief, says he wants “a safe place to buy a quality product” at the same price (clearly, he is a connoisseur). He and Mujica plan to “spoil the market” for pot dealers by undercutting black market prices. Prices will start at $1 per gram; by August, they plan to raise that to $2.50 per gram. This is a mere 1/8th of the cost of weed at U.S. medical dispensaries. Even in Washington state, where recreational marijuana was legalized last year, prices are projected to be $13-17 per gram.

Economic Significance

The two U.S. states that have legalized the recreational use of marijuana — Colorado and Washington — have high hopes for monetization: both have implemented a 25% tax on marijuana sales. Colorado projects that it will make $65-70 million from these taxes this year alone, which will be used, among other things, to fund the construction of new schools.

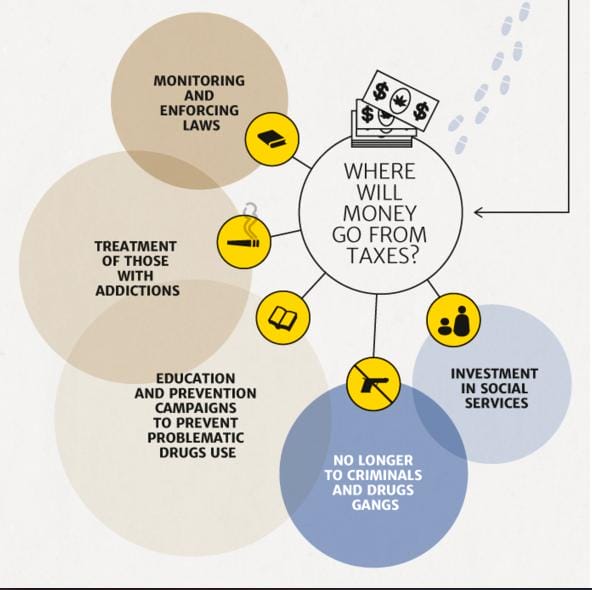

Uruguay, however, will not impose high taxes its marijuana. Because the going rate for imported Paraguayan marijuana is so low, the government is wary about maintaining competitive prices so they can thwart cartels. Many analysts question Uruguay’s ability to undercut already bottom-bale street prices. The majority of what Uruguay does collect from minimal taxes will be used to enforce laws, treat the invariable influx of drug addicts, and organize educational campaigns which will champion safe drug use.

Source: InSight

But in order to effectively unravel the Paraguayan cartels, Uruguay will have to do more than keep taxes low: the country must ensure they hire enough licensed suppliers to cultivate and produce enough product. With 70,000 consistent recreational users, Mujica estimates he’ll need 5,000 pounds every month. To achieve this, Uruguay will enlist its best asset: its farmer population. Professional agriculturalists and “crop men” will be given licenses to scale production.

But can Uruguay really compete with the low prices of Paraguayan and Mexican cartel weed?

The interactive map below delineates the flow of Uruguay’s current illegal marijuana trade.

Source: InSight Crime

Paraguay exports freshly cut marijuana at $10 per kilogram. According to self-heralded “weed experts,” only about 20% of this weight is that of the marijuana buds; an additional 75% of the buds’ weight is lost during the drying process. So, one kilogram of fresh product yields about 50 grams of smokable product. This means cartels are purchasing weed for astonishingly modest prices — as low as 20 cents per gram.

The cartel’s price points vary by geographic region. On the borders, Uruguayans might expect to pay about $1 per gram; in Montevideo, the capital, there is higher demand and prices skyrocket to as much as $5 per gram. “Ricki,” who tells us he smokes “on the daily,” says he has a connection with a local dealer, from whom he buys the Paraguayan product for about $1.50 per gram.

As mentioned, Mujica and his team plan to roll out their plan at $1 per gram, and have admitted that prices may eventually be closer to $2.50 per gram. These prices are by no means set in stone: Uruguay will need to pay farmers for crop production, fund a number of initiatives and programs, and figure out some sort of distribution model — all of which may require funding outside of potential marijuana revenues. Additionally, much of Uruguay’s plan is contingent upon quality: “Ricki” plans to continue purchasing weed illegally, unless he sees a significant difference in “bud strength.”

In any case, with high profits, cartels will probably be in a formidable position to compete at a lower price point. Despite strict marijuana laws — possession is punishable by imprisonment — Paraguay is under a stronghold by cartels. Open borders with lax enforcement, ineffective customs inspectors, and corrupt police allow cartels to effectively operate. Luis Rojas, head of Paraguay’s National Antidrugs Secretariat, is worried that Uruguay’s new bill will increase the illegal drug market he’s been trying to thwart. “It is going to stimulate internal consumption, and thus the trafficking of marijuana,” he says. He’s also “more than convinced” that drug lords will be able to undercut whatever price Uruguay sets for its legal sale of marijuana.

In the interim, Paraguayan drug lords have raised prices. Cartels are aware that legalization procedures are imminent, and they’re taking preventative measures to make as much as they can before the process is in full swing. In Montevideo, the average price of weed on the street has increased nearly 25%: before the new bill, a kilo was $375; now it’s $470.

Conclusion

While Uruguay’s marijuana legalization plan comes with good intentions, its implementation will be an arduous, lofty struggle — and not just against the black market. In the wake of creating the bill, Uruguay’s government has been lambasted from every corner of the ring.

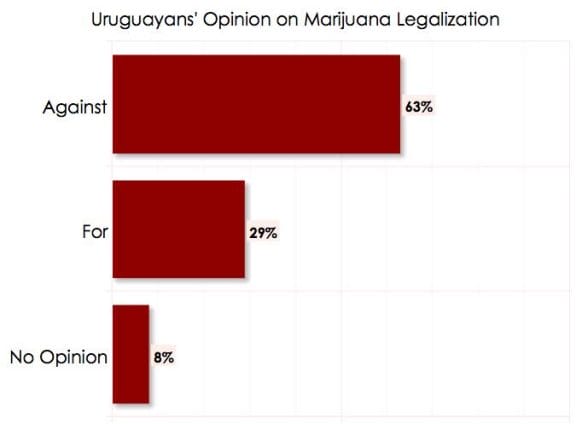

The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), a branch of the United Nations, has decried that Uruguay “is breaking the international conventions on drug control with the cannabis legislation approved by its congress.” Many psychiatrists are forecasting a spike in mental illness. Pharmacists are furious about the prospect of having to dole out marijuana, and are concerned that their public image will be tarnished. Even the country’s citizens are wary about widespread use of recreational marijuana; 63% of Uruguayans are opposed to the bill (see graph below).

Source: Factum

In the face of backlash, others claim that it’s ripe time to consider alternative solutions, like Uruguay’s, to combat the ills that come with taboo substances. One commenter on a blog writes, “The war on drugs failed 30 years ago but most politicians can’t seem to find a solution.” Another states, “Prohibition has (again) evolved local gangs into transnational enterprises with intricate power structures that reach into every corner of society, helping them control vast swaths of territory while gifting them with significant social and military resources.”

Both comments are valid. The United States alone has spent over $1 trillion enforcing drug laws and trying to shut down Mexican cartels; other countries have run resources dry fighting losing battles against drug lords. Banning substances altogether doesn’t seem to work well either: as we’ve written, when Prohibition was enacted in the 1920’s, it opened up a floodgate of unintended consequences.

John Walsh, of the Washington Office on Latin America, retains a positive but measured outlook:

“I think it will offer improvements on a whole range of measures, like reducing the revenues of criminal groups, reducing incarceration levels and probably reducing violence. But it’s not going to [completely] solve any of those problems.”

In the end, The Economist may summate the issue best: even if this bill doesn’t end up eroding illegal drug trade, it will have at least “increased the global sum of happiness at no financial cost.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.