A few years ago, George Loewenstein, Joseph Price, and Kevin Volpp started doing something most parents are familiar with: they bribed children to eat their vegetables.

Unlike parents who promise their kids dessert if they eat their broccoli, though, Loewenstein, Price, and Volpp, who are researchers in psychology, economics, and health, bribed other people’s children. For science!

The three of them partnered with several elementary schools to set up programs that rewarded children if they ate a serving of fruit or vegetables. For 3-5 weeks, children who took a serving of fruit or vegetables received a token they could use at a school store, school carnival, or book fair.

Research assistants counted how many servings the students took before, during, and after the program. They also stood by each cafeteria trash can to catch students who threw away uneaten veggies.

The research question was similar to the question in every parent’s mind as he or she bribes a child to eat healthy foods, to clean his or her room, or to memorize multiplication tables: Will they ever act responsible on their own?

“I think bribes and rewards are a slippery slope,” writes one parent in an online forum. “The conversation I heard yesterday was… Mom: ‘You need to do your summer reading tonight.’ First grade son: ‘How many Pokemon cards will I get when I am done?’”

But as the researchers explain in their paper, “Habit Formation in Children: Evidence from Incentives for Healthy Eating,” they suspected more children would eat veggies after the lunchroom-bribery program ended, because the kids would get in the habit of eating healthy.

If you’ve ever negotiated with children, the paper offers some validation: the kids did eat more veggies, even after the rewards disappeared. But psychologists can’t definitively tell you whether rewards are a bad idea, because the question of whether to reward kids for good behavior addresses widely debated questions of motivation and why we act the way we do.

Over the past 50 years, psychologists’ answer to the question of whether you should bribe your children to eat their veggies has evolved from “D’uh, of course!” to “Probably not!” to “Maybe yes?”

A Man and His Rats

When a man trains pigeons to guide bombs, you assume he knows a thing or two about motivation.

In the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, B. F. Skinner dominated the field of psychology, and he was not shy about handing out treats.

Skinner did not engage in Freudian theorizing about repressed desires: Skinner doubted that free will existed, and he believed that it was circular logic for scientists to explain someone’s actions by pointing to her thoughts and feelings.

Instead Skinner looked at how people and animals reacted to cues in their environment. His basic thesis was that animals engage more in behaviors that produce good results. He famously studied rats in cages (known as “Skinner Boxes”) and observed how they would learn to push a lever in response to cues like a light coming on—incentivized by the lever releasing food into the cage.

He used the same process to teach animals complicated tasks. He might reward a pigeon for moving its head to the left, then reward a pigeon for turning slightly to the left, and keep going, step by step, until the bird learned to spin in circles. During World War II, Skinner used the same step-by-step process to teach pigeons to guide bombs. The military never deployed his pigeons, but Skinner successfully taught them to tap on a screen to keep the target centered.

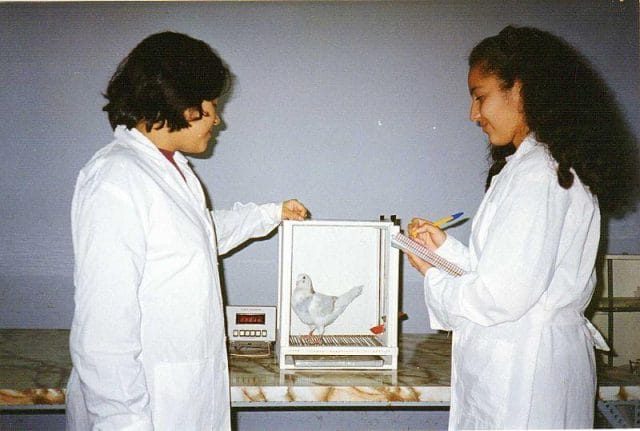

Researchers using a Skinner Box. Photo credit: Dtarazona

Skinner’s work, in the words of one psychologist, “has been applied more widely in real-world applications than any other psychologist’s,” especially in education. He recommended the same principles: break learning down into a series of small tasks—and incentivize each step.

Sometimes he actually used chocolate—as in the case of a patient with a severe mental disability who Skinner taught to identify shapes and trace out letters. In many cases, Skinner considered prompt feedback enough of a reward: He held a patent for a “learning machine” that immediately showed students if they answered multiple choice questions correctly.

The famous psychologist never weighed in on the wisdom of doling out desserts in exchange for eating carrots or offering children $5 for memorizing multiplication tables. But Skinner, the ultimate pragmatist, created a culture that was extremely comfortable with rewards.

“Do it. Bribes work. I bribe for EVERYTHING,” one parent writes on a parenting thread about rewarding good behavior. “Do it. Do it.”

Skinner would likely agree.

Psychology Goes Self-Help

Skinner and his results-oriented approach validated the use of rewards, but his successors worried about motivating people the same way Skinner motivated his rats.

More specifically, psychologists, economists, and business-types questioned whether focusing on extrinsic motivation (giving salespeople commissions for each sale; rewarding children for good grades) undermined people’s intrinsic motivation (working hard because you love your job or your classes; acting responsibly because it is the right thing to do).

In 1971, psychologist Edward Deci conducted one of the first experiments to demonstrate this effect by recruiting university students to work on puzzles over the course of 3 days.

During the second session, Deci paid one group of students—but not another—for each puzzle they completed. During the third session, Deci did not pay either group. As he did during every session, he paused the activity, made an excuse to leave the room, and observed each group through a one-way mirror.

What he saw validated his hunch that rewards killed people’s intrinsic motivation. While he was gone, the group that had never been paid kept working on the puzzles. But the other group barely spent any more time on the puzzles—and even less time than they’d spent on the first day of the experiment.

Since Deci published the results of his experiment, researchers have conducted variations that ranged from rewarding preschoolers with “a gold seal and ribbon” for drawing pictures to paying editors of a college newspaper to write more headlines. In each, people showed or expressed less interest in an activity once they’d been paid to do it.

Academics do not universally agree that rewards undermine our intrinsic motivation. For decades, researchers have reviewed these experiments and debated what they mean. Do rewards kill motivation when they are provided, like a salary, regardless of performance? Is it really a problem to offer rewards for uninteresting tasks like mowing a lawn—or eating your vegetables?

Yet the potential dangers of rewards became well established, and analyses noted that the effect was strongest in young children. The finding was part of a post-Skinner trend, ascendent since the late 1970s, that sees mental attributes as key to success.

In 1970, the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment measured preschoolers’ ability to delay gratification by waiting to eat a tasty treat until a researcher returned with a second one. Decades later, the researchers showed that the preschoolers who resisted eating their marshmallow right away performed better academically. (A finding that has since been challenged.)

Similarly, the bestselling book Drive popularized the ideas of Deci and others that people are motivated more by a desire for “autonomy, mastery, and purpose” than by financial gain.

In 2013, Dr. Angela Duckworth delivered a popular TED Talk that summarized her research on the most important characteristic of successful students and professionals: grit. “Grit is passion and perseverance for very long-term goals,” she told her audience. “Grit is living life like it’s a marathon, not a sprint.” She found that grit trumped intelligence and social background, and as a former teacher, she advocated for instilling in kids a “growth mindset.” It’s an idea developed by Stanford professor Carol Dweck: “the belief that the ability to learn is not fixed, that it can change with your effort.”

This is the research trend that makes parents feel guilty about something that was once considered routine: rewarding children for good behavior. When parents bribe children to eat vegetables, their unease is the same as Dr. Deci’s belief that rewards could prevent people from “regulating or motivating themselves.”

“When institutions… focus on the short term and opt for controlling people’s behavior,” he wrote, “they may be having a substantially negative long-term effect.”

In other words, they’ll ask for the Pokemon cards every time.

Paid Habits

Why do we do what we do?

Skinner and his peers believed that consequences shaped our behavior. They saw rewards as natural and effective tools.

Deci, Duckworth, and others believe our mindset dictates how we act and whether we succeed. They advocate for intrinsic motivation, grit, and growth mindsets.

But the newest answer from psychologists and neuroscientists is that we do what we’ve done before. They believe we need to pay attention to our habits.

To appreciate the power of habits, think about what you do when you get home from work—or get home from anywhere. Do you scroll through Facebook? Change into workout clothes? Turn on the TV? Start cooking dinner?

Whatever you do, it’s likely that you do it without much thought. You simply do what you normally do when you get home. It’s a habit.

An obviously staged photograph. Credit: USDA

As New York Times journalist Charles Duhigg explains in The Power of Habit, habits are always triggered by a cue. In this case, the cue is getting home from work. The cue then puts our brain in autopilot, as we unthinkingly act out the habit.

Psychologists and neuroscientists have a name for this autopilot: chunking. Duhigg writes:

This process, in which the brain converts a sequence of actions into an automatic routine, is called “chunking.” There are dozens, if not hundreds, of behavioral chunks we rely on every day. Some are simple: you automatically put toothpaste on your toothbrush before sticking it in your mouth. Some, like making the kids’ lunch, are a little more complex. Still others are so complicated that it’s remarkable to realize that a habit could have emerged at all.

When we engage in chunked behavior, we are very literally on autopilot. Dr. Ann Graybiel, a neuroscientist at MIT, has put rats in the same maze over and over and monitored the rats’ brains. Over time, as the rats memorized the maze and ran it routinely, their brain activity went from high to nonexistent.

Corporate America was one of the first groups to grasp the importance of habits. That’s why college students receive so many credit cards, and why marketers at Target pore over the company’s data to identify pregnant women: because those are 2 periods in life when people’s spending habits change.

Duhigg wrote his book, Habit, to help people identify habits and change them for the better—the same way he managed to change his daily cookie-eating habit while researching his book:

This is the same idea behind the lunchroom-bribery experiment we described at the start of this article. Recognizing the power of habit, the researchers wanted to see whether incentivizing kids to eat fruits and vegetables would get them in the habit of eating healthy. Other academics have tried to bribe Fortune 500 employees into hitting the gym and seniors into doing cognitive exercises meant to stave off dementia.

The studies all tend to have similar results: people do engage in the healthy habit more, even after the researchers stop rewarding them with money, stickers, or audiobooks. But, over time, the effect dwindles.

Maybe the professors just need larger budgets so they can bribe people for longer. But the main problem is likely that habits need to entail some kind of reward. The reward doesn’t need to be great: It can be a runner’s high, the satisfaction of checking items off a to-do list, or even just the relief of getting to inbox zero. But it needs to be something.

With some habits, bribing people into them may get them to experience a reward (like a runner’s high) that locks in the habit. But if there’s no upside, as most toddlers maintain after trying broccoli, the habit may never stick.

***

So should you bribe children to eat vegetables?

Parents debate and struggle with this question endlessly, and a huge market of books and articles exists to proffer advice. Almost everything people say or worry about comes from one of these three schools of thought, and all 3 have their limitations.

Bribes can be effective, but they can also backfire when children start demanding rewards. Or children may be nonplussed. “I feel like everything I read when my son was a toddler was all about tokens/points/whatever, so that was what I tried to do,” writes one parent on a parenting forum. “But he was like, ‘Sticker chart, meh, who cares.’”

The point that rewards can inhibit kids’ motivation is a good one, but it’s not always helpful when children hate a task. “I know what you are thinking. Math should be its own reward,” says one parent who rewards her daughter for finishing math problems. “It’s not.” Disinterested kids may also see right through parents’ “growth mindset” language to its manipulative intent.

And while understanding the power of habits is helpful, it’s hard enough for a motivated person to change his or her own habits. When a child has no interest in the activity, bribing them into a habit may fail. John List is a parent who paid his kids to eat fish every day during a recent vacation. “The kids have not touched fish since,” List reported on Freakonomics.

The truth is that while experts can offer helpful advice and insight, they have a lot in common with new parents: They’re still trying to figure it all out.

![]()

Our next post tells the story of a 23-year-old who unwittingly became one of the most prominent political photographers on the Internet.

To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

Photo credit for the lead photo in this article: U.S. Department of Agriculture

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. You can follow him on Twitter at @amayyasi.