Source: Stumptown Coffee

Among coffee aficionados, the AeroPress is a revelation. A small, $30 plastic device that resembles a plunger makes what many consider to be the best cup of coffee in the world. Proponents of the device claim that drinks made with the AeroPress are more delicious than those made with thousand-dollar machines. Perhaps best of all, the AeroPress seems to magically clean itself during the extraction process.

There’s really nothing bad to say about the device other than the fact that it’s a funny-looking plastic thingy. Then again, its inventor, Stanford professor Alan Adler, is a world renowned inventor of funny-looking plastic thingies; while Adler’s Palo Alto based company Aerobie is best known today for its coffee makers, the firm rose to prominence in the 1980s for its world-record-setting flying discs.

This is the story of how Adler and Aerobie dispelled the notion of industry-specific limitations and found immense success in two disparate industries: toys and coffee.

How Alan Adler Became a Frisbee Entrepreneur

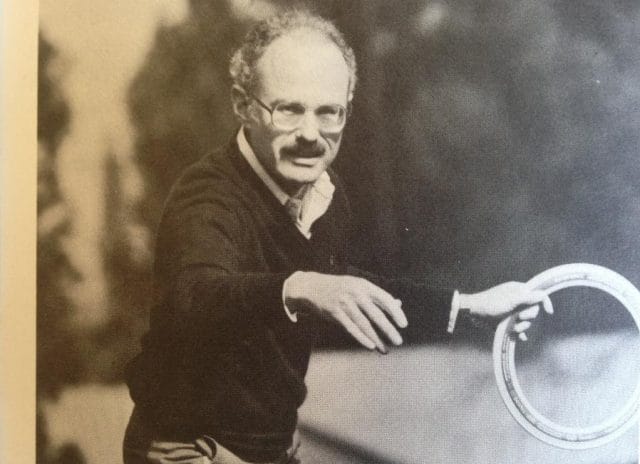

Alan Adler in the mid-1980s with an early Aerobie Pro ring

In 1938, a man named Fred Morrison was out on Santa Monica Beach with his wife when he found a pie tin. The two began tossing it back and forth and another beach-goer approached Morrison, offering him 25 cents for the tin — five times its retail price in stores. Morrison saw potential for a market.

Upon returning from World War II, he designed an aerodynamically improved plastic disc, and sold it at trade shows as the Flyin-Saucer, with the sales pitch “The Flyin-Saucer is free, but the invisible wire is $1.” After making about $2 million off his invention, Morrison sold it to toy company Wham-O in 1957, where it was renamed the “Frisbee.”

Enter Edward “Steady Ed” Hedrick, the founding father of the modern Frisbee. Hedrick reworked the rim thickness and top design of the disc, making it more aerodynamic and accurate, and is credited with propelling the Frisbee into mainstream popularity. A true man of his craft, he requested his ashes be molded into memorial Frisbees and given to family and close friends upon his death.

The Frisbee went largely unchanged for many years. Then, Alan Adler came along.

![]()

Throughout the 1960s, Adler worked as an engineer in the private sector, designing things that the average person rarely sees: submarine and nuclear reactor controls, instrumentation systems for military aircraft, and optics. He also lectured and mentored engineering students at Stanford University, where he taught a course on sensors. “I was never happier than when I was learning a new discipline,” he tells us.

This curiosity led to his pursuit of a diverse range of hobbies; as “the type of person who always seeks ways to make things better,” his hobbies invariably led to inventions. Today, he owns over 40 patents — some of which are in surprising fields.

As an amateur astronomer in the early 2000s, he ended up inventing a new type of paraboloid mirror and writing a computer program, Sec, that assisted the way astronomers select secondary mirrors. He developed an interest in sailing and proceeded to design a sailboat that won the Transpac race (from San Francisco to Hawaii). Recently, he took up playing the Shakuhachi, a Japanese end-blown flute, and has already constructed several dozen designs.

A few of Adler’s experimental Shakuhachi flutes

Adler had always been fascinated by the magical quality of flight, and, according to one publication, “combines the skill of an engineer with the skills of a practical dreamer.” In the mid-1970s, he began toying with the idea of creating a flying disc — an object that would be “easy for the average person to throw with very little effort.” He retired to his workshop and began chipping away at prototype designs, going through dozens of iterations before developing the Skyro in 1978.

Skyro throwing pictorial; Photo taken at Stanford Special Collections Library

The Skyro relied on a basic aerodynamics principle: a flying ring requires an equal amount of lift in the back and front. Unfortunately, the back end of the disc always caught the downdraft of the front, had a smaller lifting force, and prevented a stable, balanced flight. To combat this, Adler fine tuned the molding of the Skyro to create an “extremely low-drag shape.”

He took his new design to Parker Brothers, a toy manufacturer, met with one of their sales managers, and “went out in the parking lot to throw discs around for a while.” The manager was blown away by the disc’s ease of flight, but it was made out of plastic and he insisted it was too hard for recreational use. Adler had included instructions on how to line the edges with soft rubber during the manufacturing process, but this technique had never been explored, and Parker Brothers said it was impossible.

So, Adler took matters into his own hands. He went to Mother Lode Plastics, paid them “several thousand dollars,” and had custom prototype molds made. He then brought his completed vision back to Parker Brothers, who bought the rights to his invention. “They didn’t have the foresight to do something that hadn’t been done,” Adler tells us. But he did, and this wouldn’t be the last time he forged new ground as an inventor.

Early Skyro packaging; Photo taken at Stanford Special Collections Library

Under Parker Brothers’ control, the Skyro sold about a million units, according to Adler, but that “wasn’t enough to maintain their interest,” and the rights were returned to him in the early 1980s.

The Skyro had one major issue: it had to be thrown at a very particular speed in order for it to fly in a straight trajectory. When it was thrown at the right speed, it flew insane distances — from home plate, one man threw a Skyro out of Dodger Stadium — but for the average consumer, it could be difficult to determine this speed. Adler went back to the drawing board.

![]()

Six long years ensued. By day, Adler taught classes and consulted; by night, he developed the ultimate flying disc. In the January 1984, in his garage/laboratory, Adler designed a ring-flight simulator on his computer and realized that achieving a perfect balance at any speed was possible. To achieve this, he’d have to create an airfoil (a wing or blade) around the perimeter of the disc that allowed for “50% greater lift slope when flying forward than backward.”

On his fourth prototype, Adler had a major breakthrough: he molded a spoiler lip around the outside of the rim. He took his new model out to a big field on Stanford’s campus, and thrusted it into the sky; the disc flew “as if sliding on an invisible sheet of ice.”

Adler’s breakthrough prototype of the Aerobie Pro ring; Photo taken at Stanford Special Collections Library

“The first time I threw the Aerobie, I was in a state of euphoria,” Adler recalls. “It made such an impact on me. It went so far with such little effort.” Within six months, Adler’s first disc, The “Aerobie Pro,” went into independent production under Adler’s new company, Superflight, Inc (known today as Aerobie, Inc). Adler recalls the thrill of releasing his accessible invention:

“For years, in my consulting work, I worked on things the average person wouldn’t buy; it was a great pleasure to transition into products with much broader utility and distribution. Plus, discs are a whole lot of fun. When you see a beautiful flight, it elevates your whole soul.”

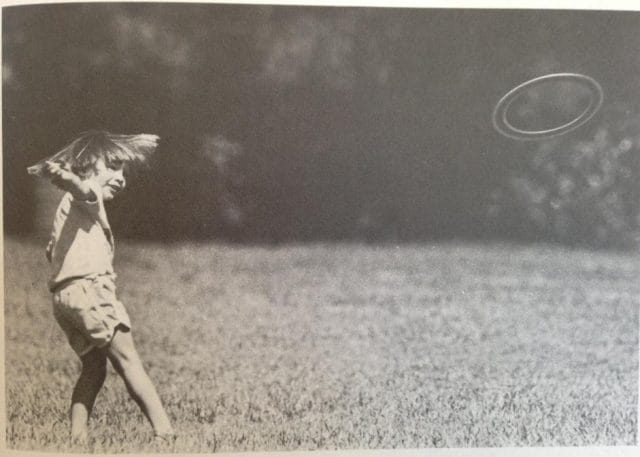

Girl with Aerobie Pro; Photo taken at Stanford Special Collections Library

A team of Aerobie enthusiasts; Photo taken at Stanford Special Collections Library

The Aerobie disc’s story — zany college engineering professor invents incredible flying toy — made for a good headline. Adler says this led to a “fabulous run of luck with publicity,” which led to the disc’s early success:

“We were on all of the networks: The New York Times, People Magazine — just about all the major news sources we wanted covered us. Stanford’s news service sent out 220 press releases about the disc.”

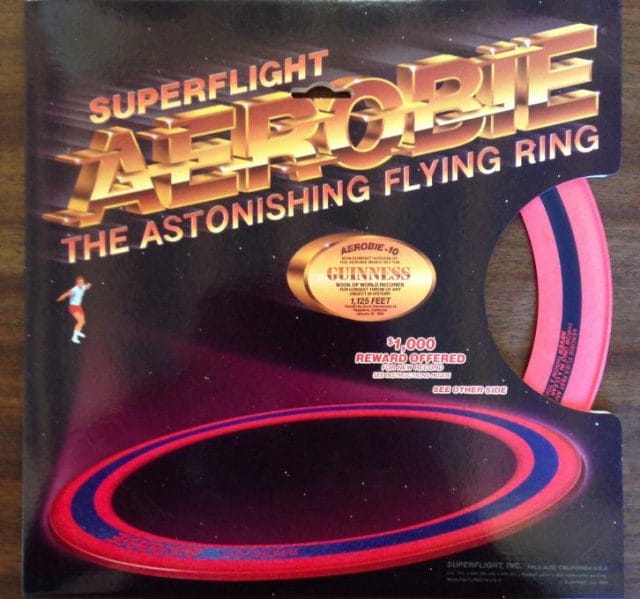

But Adler also got creative. He contacted Scott Zimmerman, a seven-time Frisbee World Champion, and involved him in a number of publicity stunts through the mid-1980s. In 1986, Zimmerman threw an Aerobie Pro 1,257 feet (383.1 meters) at Fort Funston in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, setting a Guinness World Record for “longest throw of an object without any velocity-aiding feature;” in 1987, Zimmerman, fully dressed in George Washington regalia, taped a silver dollar to an Aerobie and hurled it across the Potomac River; in 1988, he flung an Aerobie over Niagara Falls.

Adler offered a $1,000 reward to whoever could break the Guinness record set by Zimmerman. In 2003, Erin Hemmings threw the disc 1,333 — over a quarter of a mile — and collected the money. His record throw was in the air for “more than 30 seconds.”

![]()

By 1986 — two years into production — the Aerobie Pro had sold 1 million units in the United States, and another 400,000 abroad in Canada, the U.K., and Germany. Adler became a “folk hero” on the Stanford campus; the school’s bookstore sold 6,680 Aerobies in only a 10 month period — one for every two students. At the time, Adler had a goal: to beat the Frisbee’s all time sales of 10 million units. Today, he’s just about done that, he tells us: “It’s been a huge success.”

While the flying ring has been Aerobie’s best-selling toy product, the company has released an array of other aerodynamically sound toys — 18, to be exact — ranging from a football with fins to the Dogobie, a “dog-proof” disc.

Aerobie’s product line

Aerobie has also undergone a transition from selling to toy retailers to selling to sporting good stores, according to Aerobie’s business manager, Alex Tennant, who has just returned from the New York Toy Fair:

“When I came to work here twenty years ago, our largest segment of customers was toy stores; now 80+% of our sales are to sporting goods retailers. Our products sell year after year in sporting goods stores whereas toy stores and toy departments tend to feel that they must sell whatever is new.”

Adler says the mainstream toy industry has a tendency to push out new products every three years. “Parker Brothers, for instance, has a quota of ten new toys every year at the NY Toy Fair,” he tells us. Aerobie finds this practice counter-intuitive, and goes against the grain:

“A lot of companies feel the need to release new products; they’ll release products that never really deserved to be sold! They’re just not that good. We don’t look at it that way: we only release products that we think are innovative and offer excellent play value. Companies often spoil products by revising them in an effort to make them new.”

Aerobie in original packaging (1985); Photo taken at Stanford Special Collections Library

Conversely, Aerobie has stuck with a relatively small list of products (18, over a 30 year business), and has never had to discontinue a product (this is a routine practice at major toy manufacturers).

But as massively popular as the Aerobie Pro has been, it’s now the company’s number two best-selling product. Seven years ago, Adler dramatically shifted out of the toy market and into the coffee business.

How Aerobie Disrupted the Coffee Game

Source: rcakewalk (Flickr)

The AeroPress was conceived at Alan Adler’s dinner table. The company was having a team meal, when the wife of Aerobie’s sales manager posed a question: “What do you guys do when you just want one cup of coffee?”

A long-time coffee enthusiast and self-proclaimed “one cup kinda guy,” Adler had wondered this many times himself. He’d grown increasingly frustrated with his coffee maker, which yielded 6-8 cups per brew. In typical Adler fashion, he didn’t let the problem bother him long: he set out to invent a better way to brew single cup of coffee.

He started by experimenting with pre-existing brewing methods. Automatic drip makers were the most popular way to make coffee, but “coffee connoisseurs” seemed to prefer the pour-over method — either using a Melitta cone (or other variety), or French Press. Adler quickly found the faults in these devices.

The Melitta cone, a device you place over your cup with a filter and pour water into, has “an average wet time of about 4-5 minutes,” according to Adler. The longer the wet time, the more acidity and bitterness leech out of the grounds into the cup. Adler figured this time could be dramatically reduced, quelling bad-tasting byproducts.

It struck Adler that he could use air pressure to shorten this process. After a few weeks in his garage, he’d already created a prototype: a plastic tube that used plunger-like action to compress the flavors quickly out of the grounds. He brewed his first cup with the invention, and knew he’d made something special. Immediately, he called his business manager Alex Tennant.

Tennant tasted the brew, and stepped back. “Alan,” he said, “I can sell a ton of these.”

A year of “perfecting the design” ensued: Adler tried out different sizes and configurations, and at first “didn’t understand the right way to use [his] own invention.” The final product, which he called the AeroPress, was simple to operate: you place a filter and coffee grounds (2-4 scoops) into a plastic tube, pour hot water into the tube (at an optimal of 165-175 degrees), and stir for ten seconds.

Now comes the fun part: you insert the “plunger” into the tube and slowly press down; the air pressure forces the water through the grounds and into your coffee mug that’s (hopefully) positioned below. This produces “pure coffee” that is close to espresso in strength, and can be diluted with additional water. The process of plunging the tube also self-cleans the device, but Adler says this was simply “serendipitous.” After all, great inventions, he says, “always require a little luck.”

An AeroPress fan’s artsy instructional video

Alan’s new method shortened the typical wet time of other makers from 4-5 minutes to one minute. Not only that, but Adler claims his paper filters (which run $3.50 for 350, and are reusable up to twenty-five times each) reduce lipids that typically incite the body to produce LDL cholesterol (this is debated greatly in the coffee community).

With his plans mapped out, Adler went to Westec Plastics in Livermore, California, ordered $100,000 worth of molds, and put the invention into production. In 2005, Tennant and Adler debuted the product at Seattle’s Coffee Fest, where it was “extremely well accepted by the coffee aficionado community. ” Brewers loved the easily “hackable” design of the AeroPress; it’s list price — $29.99 — didn’t hurt either, especially when gauged against coffee makers ten to fifteen times the cost.

Despite a great showing, initial success didn’t come easily for the AeroPress. Tennant recalls pleading with one prominent sales rep group not to drop the product due to low sales. As Adler recalls:

“Aerobie spent over 20 years establishing distribution for sporting goods, and all of a sudden, we were confronted with creating distribution for kitchenware. We didn’t leap into this lightly.”

The AeroPress struggled over the next few years; at one point, 2007 sales were even lower than 2006 sales and it appeared as if the product would fizzle out and flop. After years of familiarizing himself with the sporting goods market, Tennant was tasked with convincing house-ware distributors and retailers to sell “an odd looking, completely new kind of coffee maker made by a toy manufacturer.”

Coffee puck left over from AeroPress use; demonid (Flickr)

When the AeroPress hit the market, the competition was formidable. “If you had walked down the coffee maker aisle at Target, you would have found many 8 to 12 cup drip coffee makers that sold for $20 to $50,” says Tennant. But the gadget distinguished itself as part of the new trend of one-cup brewers that believed “fresher coffee is better coffee.” Tennant continues:

“The AeroPress was part of a movement to quality in coffee and also part of a broader movement to quality in food and beverage. Look at the success of craft beers. Look at the popularity of celebrity chefs.”

The company relied on its product’s strong suit: the thing brewed a mean cup of jo. They voraciously attended trade shows, and sent out free products to coffee experts and food writers, and in 2008, sales began to slowly pick up. Aerobie had faith in the superiority of the AeroPress; soon, others did too. Tennant reiterates:

“There is no question the performance of the AeroPress and the delicious taste of the coffee it brews is the fundamental reason our strategy works.”

![]()

The coffee community is rather fanatical; one popular forum, CoffeeGeek, boasts 82,000 members who debate everything from latte art approach to water dilution ratios. “Aerobie AeroPress,” a thread created in 2005, is the largest thread on the entire forum, with over 7.3 million views and 2,700 posts. Adler joined the site, led discussions and answered questions — 683 to be exact — for his customers directly on the site:

The AeroPress took off; soon they had people contacting them from all over the world, interested in purchasing one. Whereas Alder had previously relied on traditional media and television to market his flying discs, the internet brought the AeroPress great success — specifically internationally:

“You would not believe the coffee shop owners in remote corners of the world who contact us and ask how they can buy some AeroPress coffee makers. I guess the message is those corners are no longer so remote with the internet.”

The World AeroPress Championship started at the behest of a Norwegian brewer who loved the product. Competitors use the AeroPress to brew the best cup of coffee, which is judged using a blind test. Some of them get pretty crazy, says Adler: “brewing upside down is a big thing. I don’t know if it’s effective or not, but people have tried all sorts of things.” Today, the World AeroPress Championship has attracted competitors from around 25 countries, and has helped to boost international sales to 38% of Aerobie’s overall revenue. The AeroPress has seen especially strong sales in northern Europe (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland), where they “are very serious about their coffee;” the product is now sold in 56 countries worldwide.

AeroPress fanaticism taken to another level

Today, the AeroPress is Aerobie’s best selling and fastest growing product; it accounts for nearly half of all the company’s sales. Since 2005, Aerobie has sold over one million units and Tennant says the product is still gaining traction.

![]()

The AeroPress’s “hackable” nature has led to a variety of barista-made supplementary inventions. The S-Filter, a reusable metal filter for the AeroPress, was invented by Seattle-based Keffeologie in 2012. The company, started by two coffee-loving friends, raised over $30,000 on Kickstarter with only a $500 initial goal.

Portland-based Able Brewing Equipment invented a little stopper to convert the AeroPress into an on-the-go cup. Numerous companies have also made specialized brew stations for the device.

There is also a heated debate among coffee pros as to whether brewing right side up (as intended), or upside down (inverted) is superior when it comes to taste. Some claim that the inverted method results in “total immersion brewing” like that of a French Press; others say the method is just a fancy way for baristas to distinguish themselves. Adler doesn’t think the inverted method makes any difference in taste, and says “about half” the winners of the AeroPress World Championships do it this way, and the other half don’t.

Reflections on Inventing

Alan Adler’s two-car garage in Los Altos, California isn’t much good for parking.

“There’s no way you can get a car in there,” says Tennant; “it’s just not going to happen.” Two large industrial tools — a lathe, and a milling machine — take up most of the room’s space; boxes of prototypes, plastic molds, and relics of foregone creations are packed into every other conceivable nook and cranny. In here, says Adler, “the inventions are born.”

A few times a year, Adler packs a small book bag and heads to his local junior high school to teach students some of the things he’s learned in this garage over the years. Most of his students have no idea who he is, but have probably tossed around an Aerobie Pro. Adler’s inventions have snaked their way into everyday use in society, and his inventing tips are prescient. He imparts five of them to his class:

1. Learn all you can about the science behind your invention.

2. Scrupulously study the existing state of your idea by looking at current products and patents.

3. Be willing to try things even if you aren’t too confident they’ll work. Sometimes you’ll get lucky.

4. Try to be objective about the value of your invention. People get carried away with the thrill of inventing and waste good money pursuing something that doesn’t work any better than what’s already out there.

5. You don’t need a patent in order to sell an invention. A patent is not a business license; it’s a permission to be the sole maker of product (even this is limited to 20 years).

But Adler possesses a sixth skill that can’t be taught: tenacity. In the face of failure, he persists with a level head. Neither the Aerobie Pro, the AeroPress, nor any of his other 17 inventions came easily. But as Adler says, “inventing is a disease and there is no known cure.”

Alan Adler (right) imparts some wisdom on a young whippersnapper

As we sit together in the Stanford Special Collections library going through a box of his old prototypes, Adler tells me that the Skyro wasn’t actually his first invention. A few years prior, he’d created a Slinky-like plastic toy called the Slapsie; he was convinced it was going to be a blockbuster. He took his wooden prototype to Wham-O, and they rejected it. He took it to Parker Brothers, and they rejected it. He took it to 11 other companies; each time, he was turned away.

Instead of giving up, Adler invested thousands of his own money constructing his own plastic prototypes, re-molding, and re-designing the toy. In a classic toy inventor move, he packed a small suitcase full of Slapsies and journeyed to Los Angeles to meet with the companies again. This time, Wham-O bought the rights.

![]()

Adler sifts through the collections, adjusting his glasses and inspecting each item with care. “I haven’t seen these in twenty years,” he tells me, running a finger across his pencil-thin mustache. For nearly an hour, he examines his old toys, pausing to tell me the stories behind each — quite loudly, to the library staff’s displeasure. We watch a video reel of old Aerobie news spots; early 80s Alan is animated, enthusiastic, full of life and vibrancy.

Before he leaves, Adler pulls aside a Stanford library employee. “I’m Alan Adler, inventor of the Aerobie,” he tells the kid. “I’d like to donate my notebooks when I die; is that something I should handle through you?” The employee, no more than 20 years old, seems a bit taken aback, but sits down with Adler and discusses what the notebooks contain: decades of designs, equations, graphs, musings, ideas — a treasure trove of ingenuity.

But the notebooks also contain years of failure, frustration, miscalculation. At every turn, the AeroPress — like most of Adler’s other inventions — encountered innumerable roadblocks, faced skepticism, and was doubted. Like anyone who has forged new ground, Adler had a choice at each junction: throw in the towel, or return to the drawing board; he consistently chose the latter. In many ways, the AeroPress is a reflection of its inventor: it’s simple, but precise, it’s highly adaptable, and it squeezes every last drop of flavor from the bean.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.